MICHAEL DONNAY

Or, A Brief Meditation on Why Everyone Wanted You to Stop Drinking

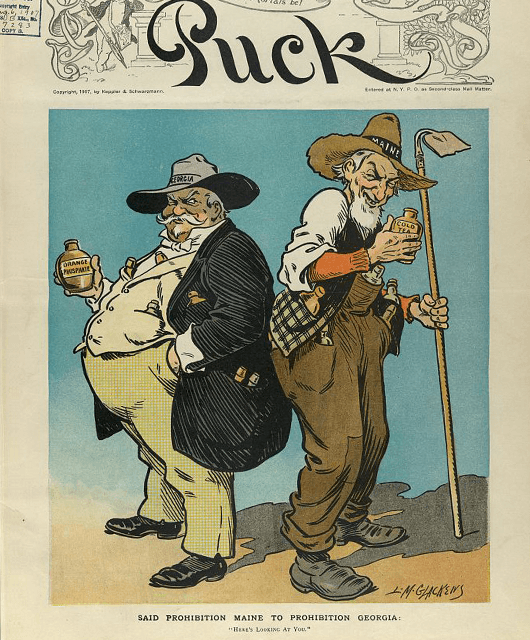

In the space of two months at the end of 1918 and the beginning of 1919, both houses of Congress and 36 states approved one of the most radical social experiments in history: the total prohibition of alcohol in the United States. Less than five years earlier, only nine states had any type of statewide ban on liquor. How then, in such a seemingly short time, did the United States go from being a nation of drinkers to a dry country? The easy answer is that it didn’t — as the repeal of the 18th Amendment a scant 13 years after its passage made clear — but the question of how the nation got to this step in the first place is more complicated. There were a number of other models for regulating the liquor industries from both Europe and the Untied States available to reformers at the time. In Sweden, each person was issued an alcohol ration book that limited their intake, while Austria strictly enforced an early closing time on all public houses. States like Georgia had experimented with state-run liquor stores and a number of states had attempted to set limits on the amount of liquor a single person could purchase. Yet, with all of the options available, the temperance movement advocated for and won a total prohibition on the sale of alcohol.

Prohibition in the United States: National Ban of Alcohol | Source: © WatchMojo.com/YouTube

In many respects, the passage of the 18th Amendment proved an unlikely victory for the American temperance movement. After a series of unsuccessful statewide attempts to prohibit alcohol sales in the 1850’s, total prohibition came to be viewed by many as politically infeasible. Even as the movement gained steam in the later part of the 19th-century, the majority of states that did prohibit certain types of alcohol production and consumption did so through regulation. The very name of the movement nodded to its goal; for all that many reformers wanted total prohibition, temperance and moderation were the goals within reach, politically. And yet, by 1917 all but three states had either statewide prohibition or allowed local governments to prohibit alcohol. How then did the movement gain momentum so quickly? As with most moral crusades in American history, the credit goes to a confluence of long-term social trends and pragmatic political expediency.

Although many of us view early European colonists, especially the Puritans, as morally upright (or uptight) and opposed to anything that could be construed as enjoyable, the temperance movement as a political force was not born out of Puritan prudishness. In fact, prior to the early 19th-century, it was almost nonexistent. During the entire colonial period, alcohol was a regular part of nearly every colonist’s diet. Its restorative properties were widely praised and, in a period when drinking water was ill advised, was often used as a simple thirst quencher. Early colonial governments took a rather pragmatic approach to controlling alcohol; there were restrictions on the operation of taverns, who could buy it (slaves, indentured servants, and known drunks were the most commonly excluded), and what activities could accompany public drinking. But alcohol also served as an important tax base for colonial governments, with taxes on both imports and domestic production supporting projects like public education and military defense. Local social pressure and what little regulation did exist proved more than enough deterrent against excessive public drunkenness. When it was condemned, it was in the guise of a personal failing and not a larger societal issue.

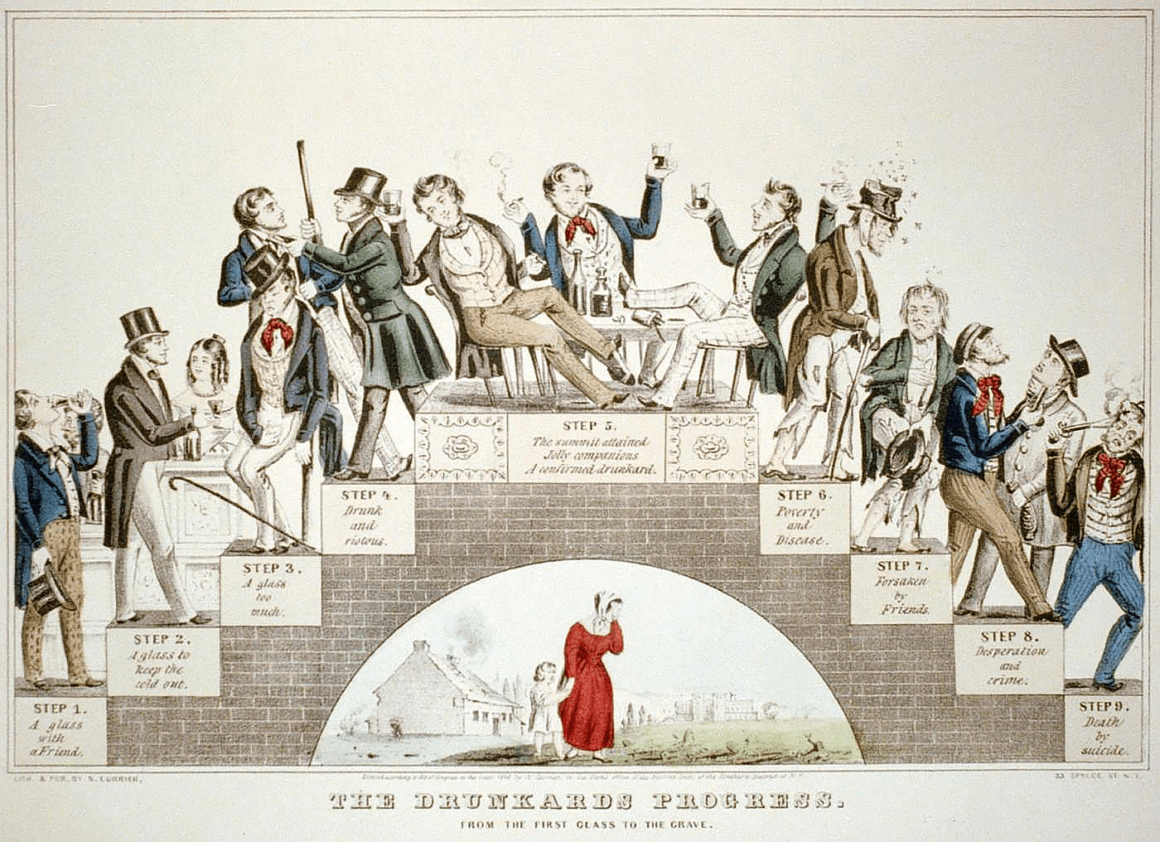

The Drunkard’s Progress, an 1846 lithograph by Nathaniel Currier | Source: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

1907 Puck Magazine cartoon by L.M. Glackens, titled “Said prohibition Maine to prohibition Georgia: Here’s looking at you” | Source: Library of Congress

This changed with the arrival of large quantities of molasses from the West Indies in the 17th-century and the subsequent rise of a domestic rum industry. An integral part of the “triangle trade,” this rum was simultaneously cheaper than other imported spirits and more alcoholic than domestically produce ciders and brandies. This combination brought about a dramatic expansion of taverns and a subsequent weakening of the social norms around drinking. Formerly the exclusive purview of the social elite and thus under their close supervision, tavern ownership was democratized by the middle of the century. As the number of taverns grew — in Boston the number doubled to over 150 in 30 years — public drunkenness became more visible and began to draw the ire of moralists as a societal issue rather than a purely personal one. John Adams, never one to pass up an opportunity to complain about his neighbors in Boston, railed “against ardent spirits, the multiplication of taverns, retailers and dram shops and tippling houses [in the city].” Disruptions in trade brought on by the American Revolution decreased the role of rum in American life by the end of the 18th-century, but this created an opportunity for Scottish and Irish settlers to create a domestic whiskey industry in its place. In the same year the Constitution was ratified, the first barrel of Kentucky whiskey was made and, with it, the moral crusade against drunkenness was here to stay.

For the next several decades, the growth of the United States and the increase in alcoholic consumption went hand in hand. The expansion westward was driven by whiskey profits and the urban expansions on the East Coast provided an exuberant market for domestic and imported spirits. The country as a whole was experiencing an array of social upheavals as it developed a national economy, national identity, and continued its relentless expansion west. With these upheavals came a sense of growing social unease, especially among the upper classes, and in many people’s minds the chaos of the expanding nation, especially in the cities, was intimately tied with drink.

Increasingly, drunkenness became seen as a nexus of a range of social ills and the war against liquor morphed into a metaphor for the struggle to save society from degeneration.

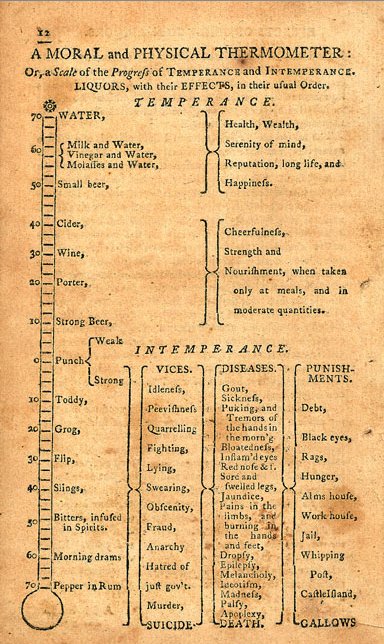

“The Moral Thermometer,” from Benjamin Rush’s An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind | Source: Library Company of Philadelphia/Wikipedia

Because of this, people began focusing on drunkenness as a social problem to be solved. Benjamin Rush, a physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, published an enormously influential tract called An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind, which sold over 200,000 copies in the first decades of the 19th-century. In it, he argued that alcohol didn’t have inherently beneficial properties, but rather was a poison to both moral and physical health. Rush was one of the earliest American writers to frame alcoholism as a disease instead of a moral failing and he identified distinct social effects of excessive alcohol consumption that could be remedied through social action. He believed that the only cure for drunkenness was complete abstinence from drink and that societal pressure must be brought to bear in order to discourage the consumption of alcohol. These beliefs, which spread widely in the early 19th-century in large part because of Rush’s writings, would become central to the American temperance movement.

From the 1830’s through the end of the civil war, the temperance movement simultaneously expanded and fractured. Organizations regularly formed, splintered, and collapsed. In such a competitive environment, as these various groups vied for supporters and public attention, moderate organizations found their voices drowned out by the more vocal and extreme groups. Increasingly, drunkenness became seen as a nexus of a range of social ills and the war against liquor morphed into a metaphor for the struggle to save society from degeneration. Whereas many temperance supporters earlier in the century had seen beer and wine as viable alternatives to spirits, most groups increasingly called for the total prohibition of alcohol in all of its forms.

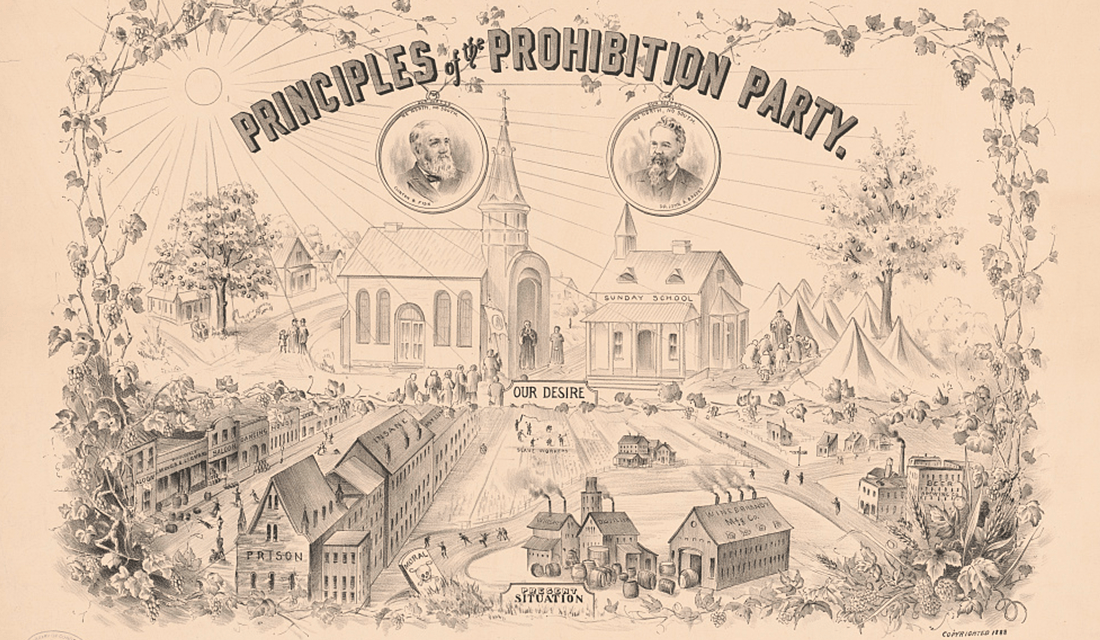

The end of the Civil War saw many former abolitionists take up the moral cause of prohibition; when the Prohibition Party formed in 1869, it branded itself as the direct descendent of antebellum abolitionists. Although the party had an inauspicious beginning, its step into national politics laid the groundwork for a wave of more effective political organizations aimed at removing the “scourge of drink” from the United States.

Poster depicting the Principles of the Prohibition party, made in c. 1888 | Source: Library of Congress

A whole host of groups took up the cause of prohibition as the 19th-century came to a close. The majority of these groups belonged to a broad political movement born out of the dramatic socio-economic shifts of the post-Civil War period called the Progressive Movement, which was a catchall term for an array of social, political, and economic causes pursued in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Progressives were interested in reforming all aspects of American life and often believed that government intervention, when effectively directed, could be a powerful tool for doing so. As such, the cause of prohibition was widely supported by progressive groups. They saw it primarily as an issue of political corruption. During this period, party machines controlled the levers of government in most major cities through a system of patronage that often centered on local saloons or pubs. There, party bosses would distribute favors — often in the form of free liquor — in return for votes. Progressives saw this system as an impediment to their broader campaign for reform and believed that shuttering the saloons would be one way to reduce these politicians’ power.

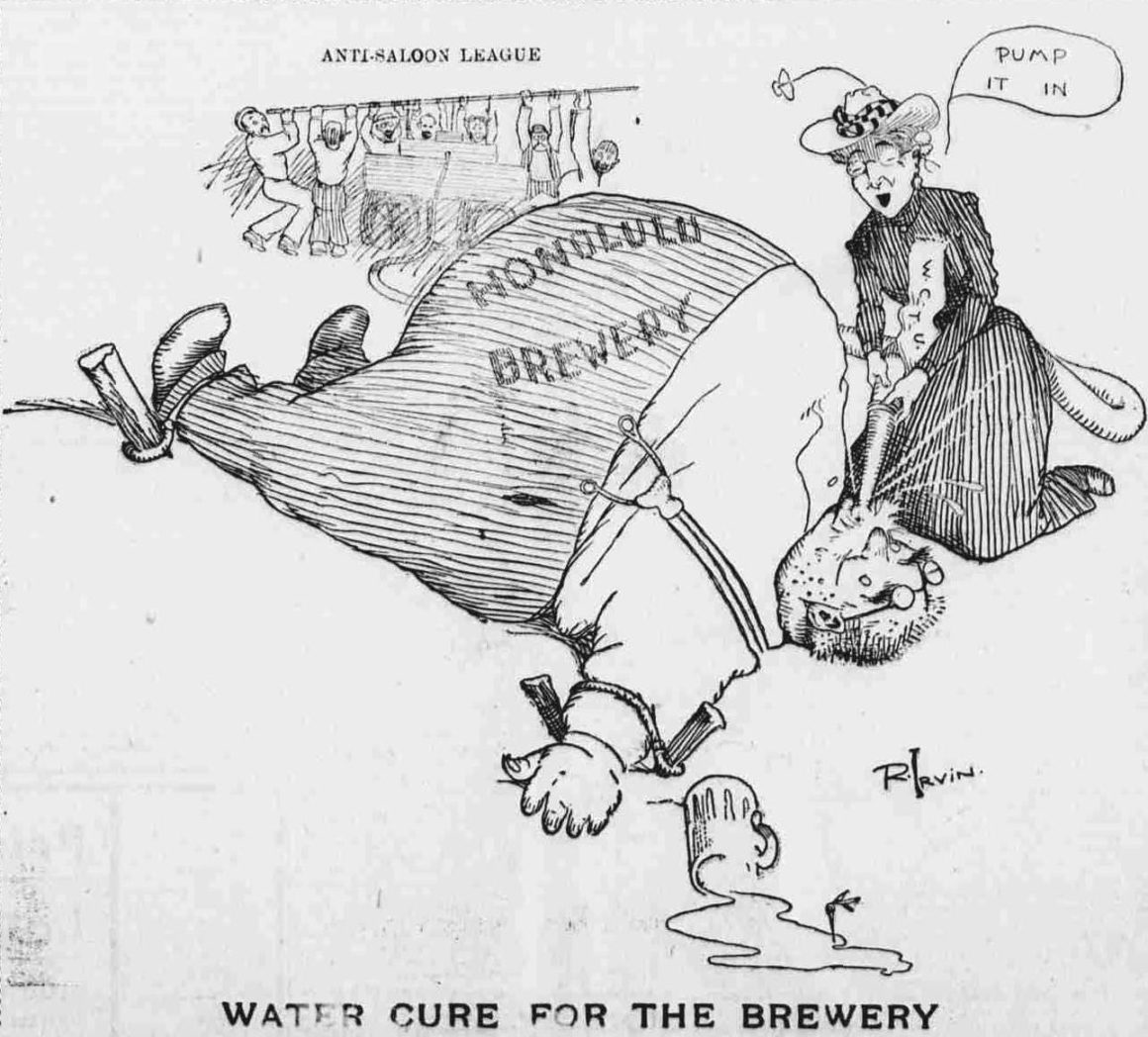

Hawaiian Gazette cartoon from 1902, depicting both the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union | Source: University of Hawaii at Manoa Library/Wikimedia Commons

The two biggest players in the temperance movement at this time were the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Although they both supported the same policy goal — total prohibition — they came at the issue from two different angles. The ASL was the more pragmatic and, thus, the more influential of the two. It pioneered modern pressure politics by mobilizing large groups of voters around the question of prohibition. It would then wield these voters as a threat over politicians, promising to support those who voted for prohibition and oppose those who did not. The ASL’s success in appealing to voters was largely due to its willingness to use any argument that would work: depending upon the audience, ASL campaigners would play on moral sentiments, public health concerns, or racial fears. In contrast, the WCTU took a much more religiously oriented view. It had as its mission the creation of “a sober and pure world” through, among other things, the total prohibition of intoxicating liquors. In a period where the women’s suffrage movement was still considered too radical by most middle-class women, the WCTU offered a more appropriate avenue to channel their political energies. With over 200,000 members at its height, the WCTU became one of the most powerful forces in American politics at the turn of the century.

While many members of the ASL and the WCTU were campaigning for prohibition because they believed alcohol was harmful in its own right, there were also significant racial, ethnic, and religious biases at work. The ASL was willing to collaborate with almost any organization that would support its prohibition agenda, including hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Although the KKK was primarily a racist and nativist group, it had taken up the cause of prohibition because alcohol, race, and immigration were intimately connected in contemporary discourse. Prohibition and calls to “clean up communities” served as dog whistles to KKK supporters and allowed the group to expand its recruiting efforts. In the South, the Klan and the ASL become so intertwined that one Alabama newspaper wrote, “it is hard to tell where the Anti-Saloon League ends and the Klan begins”.

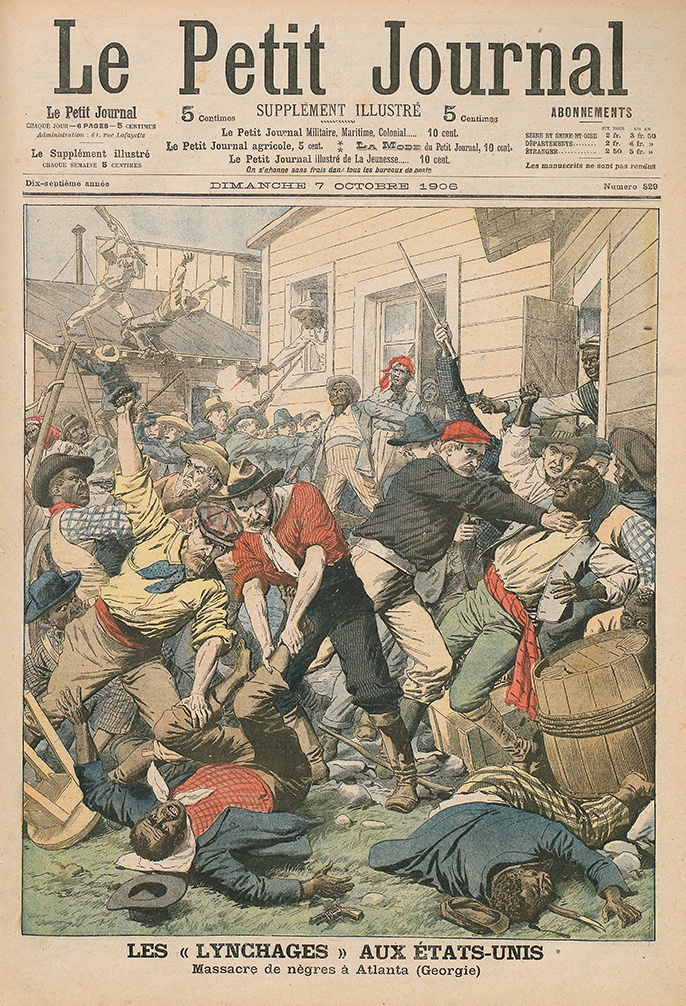

Cover of French magazine Le Petit Journal in October 1906, depicting the Atlanta race riot | Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de France/Wikimedia Commons

Southern evangelicals, including those not affiliated with the Klan, were also vocal supporters of prohibition. The 1890’s saw the resurgence of large-scale mob violence against African Americans. The hysteria that swept through the South in the early 1900’s over black men allegedly attacking defenseless white women while drunk played directly into the prohibitionists’ hands. Prohibition was marketed as a way of solving the region’s “race problem” by removing the alcohol that many whites blamed for the “bestial” nature of black men. When a race riot caused the destruction of large swaths of Atlanta’s African American neighborhoods in 1906, the local press blamed the violence on saloons and cheap liquor. Many Southern politicians also blamed alcohol for black voters’ refusal to support the Democratic Party, alleging that wet candidates were routinely buying their votes. Thus, prohibition came to be viewed by Southern whites as a silver bullet for all of their racial issues.

Similarly, many native-born Americans came to view prohibition as a solution to a problem they saw plaguing Northern cities: immigrants. The late-19th and early-20th centuries saw a huge influx of immigrants, many from Central and Eastern Europe, into the urban centers of the United States. These immigrants, especially those from Ireland and Germany, brought with them a drinking culture that many nativists saw as antithetical to the traditional Anglo-Saxon lifestyle of the American middle class. Frances Willard, the president of the WCTU, complained that, “Alien illiterates rule our cities today. The saloon is their place; the toddy stick their scepter.” Since many of these immigrants were also Catholic, nativism combined existing American ethnic and religious prejudices into a powerful political force.

No public relations campaign would be able to counter the powerful convergence of opportunistic temperance organizations with a host of political and social developments.

In addition to the longer term social influences working towards prohibition, two largely unrelated events contributed to the momentum of the movement in the early 20th-century. In February 1913, the 16th Amendment was ratified, allowing the federal government to collect income tax. The idea of a federal income tax had been a Progressive project since the 1880’s and was variously supported by socialists, populists, and the Democratic Party. Prior to ratification, the federal government derived most of its income from import tariffs and excise taxes on, among other goods, alcohol. This made prohibition an unlikely move on a federal level, as it would deprive the government of a significant portion of its revenue. However, the income tax freed the government from this constraint and in turn made total prohibition politically viable on a national scale.

The other event was the United States’ entry into World War I in 1917. As part of the wider rationing effort, President Woodrow Wilson issued an executive order that banned the distillation of alcohol and limited beer production in an effort to conserve grain. In September, he issued a further order banning beer brewing for the duration of the conflict. Wilson in effect created national prohibition until the armistice in November 1918. This experiment with national prohibition gave the temperance movement valuable support; the patriotic fervor of the war made it difficult to oppose the measure. In addition, the war produced widespread anti-German sentiment. The ASL and other prohibition groups were able to harness their anger for their cause since German-American families owned the largest brewing companies in the country. One publication called Milwaukee’s brewers “the worst of all our German enemies,” even though all of the companies were run by American citizens. It became increasingly difficult for the brewers to counter these sentiments and their argument that taxes on beer were vital to support the war effort fell on deaf ears.

As with most moral crusades in American history, the credit [for prohibition] goes to a confluence of long-term social trends and pragmatic political expediency

In many ways, the inability of the brewers to defend themselves is emblematic of the power of the Prohibition movement by 1917. No public relations campaign would be able to counter the powerful convergence of opportunistic temperance organizations with a host of political and social developments. The American entry into the war might have been the event to push things over the edge, but only because a century of activism had created the political landscape where total prohibition seemed like a reasonable policy option. Prohibition was not inevitable, but once the long-standing social forces combined with short-term political events it was a difficult to force to oppose.

While the ratification of the 18th Amendment was not preordained, the moral impulses underlying it are more difficult to discount. Although Prohibition is widely regarded as a failure today, the political rational behind it continues to motivate America’s current moral crusade: the War on Drugs. Born out of a similar mix of racial fear, paternalist government policies, and a collection of interests who prefer total prohibition to regulated use, contemporary drug policy can be easily seen as a direct successor to Prohibition-era enforcement tactics. In its selective application and its disproportionate effect on marginalized communities, the two are nearly identical. The only meaningful difference is in scope and impact: Prohibition lasted 13 years, the War on Drugs will soon enter its 50th.

Jay Z – The War on Drugs: From Prohibition to Gold Rush | Source: © Drug Policy Alliance/YouTube