KELLY VICARS

The Art Party

“More fire!!”

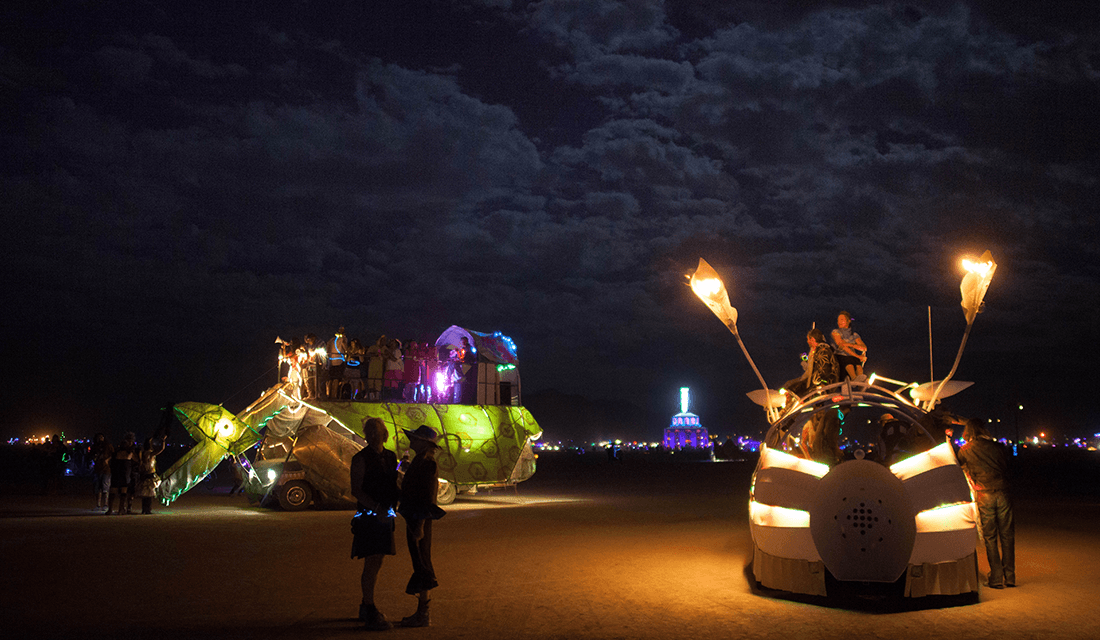

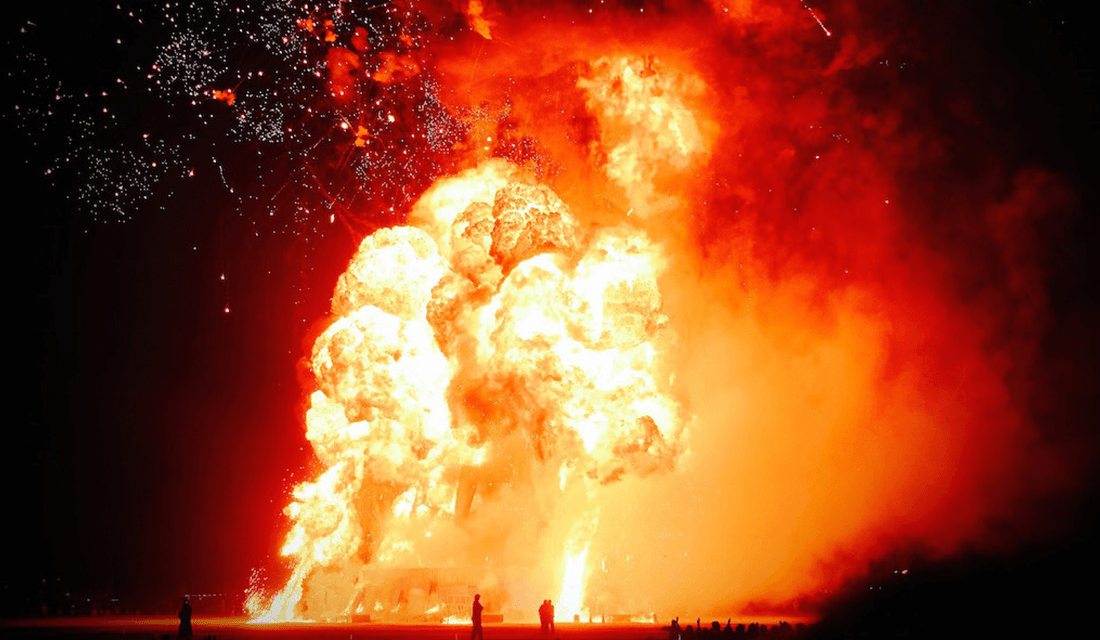

My friend Sean and I howl into the night. A half-second later, we’re engulfed by the incendiary glow of eight combustion columns shot skyward from a 30-foot tall metal octopus’ undulating tentacles.

Source: Ian Norman/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

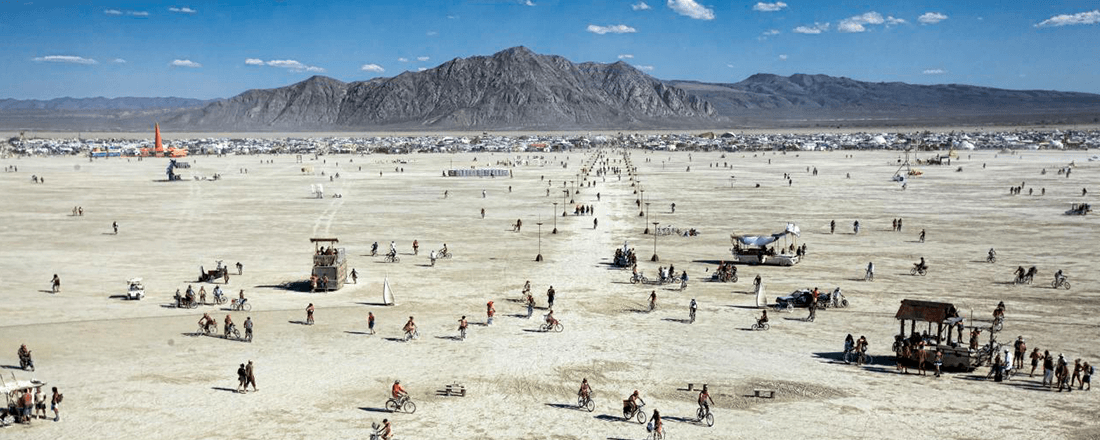

It’s 2 A.M. on a Tuesday night at Burning Man and we’re strolling “the playa,” critiquing art.

This is itself art, of course. To critique art at the annual desert festival would be a farcical inversion of the logic that abides here. Sure, everyone has opinions and favorite pieces, but Burning Man art exists beyond the pale of the mainstream art world and its galleries, critics, and unruly tides of acclaim. At museums and online, we view art from a distance. At Burning Man, we climb on it, beat drums to make it come alive, curl up underneath it, lose ourselves within its folds. Art is for everyone. You don’t need critical theory to appreciate it and you don’t need credentials to build it.

All you need are people crazy enough to help you bring it to life.

Black Rock City | Source: Christopher Michel/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

We all have big ideas, but only some of us entertain them.

A Public Built for Art

Bike onto “the playa” at any hour of day and enter a garden of the beautiful and the bizarre. There is a couple with a rickshaw serving homemade chai tea; a snarling, spinning steel warthog with 25 people yowling from its back; a giant vacuum cleaner trailing a two-story sheep through the dust. Denizens of Black Rock City dress like heroes and heroines from dystopian steampunk and sci-fi novels. Some wear gargantuan headdresses made from deconstructed Adidas sneakers and feathers; others wear nothing at all. People give each other gifts; children ride by on a mechanized cupcake. In the Thunderdome, opponents suspended in bungee harnesses fight one another (consensually) with foam bats. Most of the “rules” at Burning Man (there are 10 of them) begin with the word “radical:” radical inclusion, radical self-reliance, radical self-expression.

Art isn’t what you do at Burning Man. Art is what you are. Black Rock City has no consumer economy. Nothing is bought or sold, save coffee and ice (come on, we’re surviving here!) It dawned on me my first year as I was biking back to camp at dusk with my friends, relishing the descent of hazy lilacs and deep pinks, the expectant pause before inhalation and the night’s bloom into fluorescent cacophony: Burning Man is an economy of joy.

This looks like art. Lots of it.

Art becomes the city’s connective tissue and raison d’etre. As Burning Man founder Larry Harvey explains:

“In a world where people gather at shopping malls while they ignore city hall, and the public square is disappearing, anything that can take values and interject them into the realm of civics is terribly needed. By putting art at the center of our city, we are doing that. We are saying that art influences and elevates our civic enterprise into meaning.”

– Larry Harvey

Source: Ian Norman/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Most Burning Man art is too big and too complex to be built by one artist alone. Designing, prototyping, and staging sculptural works on the playa requires a dedicated team, willing to endure the extreme conditions of this moonscape staging ground. While the city flowers only for a week, the art quietly takes root off playa in the off season – in garages, urban warehouses, vacant fields and parking lots, inspiring large-scale collaboration amongst cross-sections of artists and participants year round. Pending approval from Burning Man Arts, you can do or create whatever you want.

You just have to get it there.

Mojave

This is Your Captain Speaking

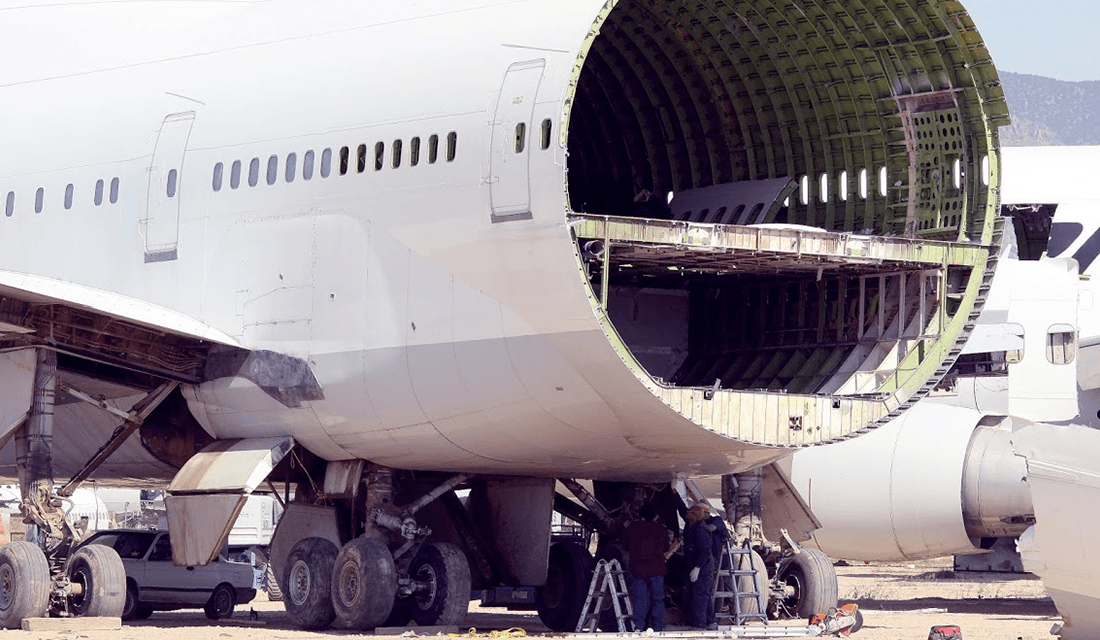

Imagine a surrealistic parking lot of abandoned and gutted airships, some with whole sides hanging open. Around the planes lies wreckage: airplane parts, steel trusses, ballast tanks, whole wings. You’re seeing airplanes, in a graveyard, in the desert. There’s something gloriously indefatigable about these flying machines. Even dismantled, they reek of optimism. They want to fly.

Source: © Big Imagination

Ken Feldman | Source: © Big Imagination

I’m standing at the Mojave Air & Space Port with a circle of volunteers clad in safety goggles and yellow earmuffs. At our center is a man with thick, Einstein hair wearing a navy blue jumpsuit. Ken is our proverbial captain — proverbial because he captains “the ship,” the Boeing 747 towering about us — yet he resists the title. This project isn’t his — it’s all of ours.

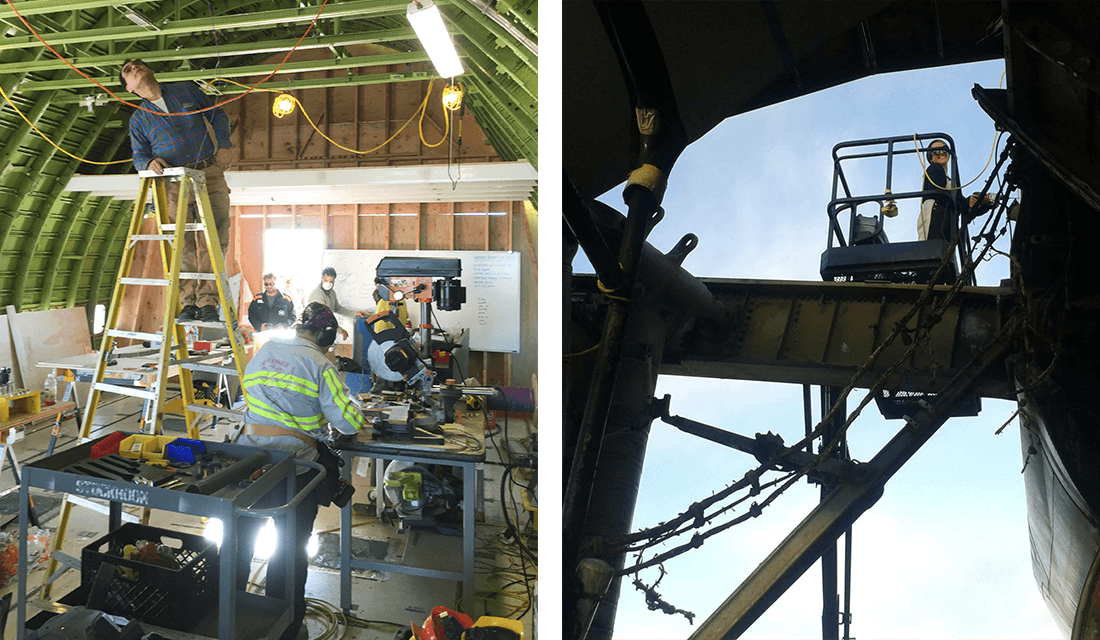

The safety briefing kicks off with a friendly warning about our desert environs. In the Mojave, anything that survives outside can kill you. There are scorpions, fire ants, rattlesnakes, Africanized bees. Later, we find a black widow in the porta potty. And that’s just on the ground. We ascend the yellow “air stairs” into the aircraft’s enormous hull and snake through the workspace, where veteran volunteers are busy drilling out rivets, ripping insulation from the cargo bay, rigging an electrical system, and building a set of 15 foot-high steel doors. To our left, a chop saw sends a volcano of sparks flying. We’re in an industrial machine shop, three stories up in the air. Ken calls over his shoulder, “Don’t use any tools you’re not comfortable with! And don’t be afraid to ask questions – we’re here to learn.”

Source: Kelly Vicars

“Safety third!” yells one safety-protected volunteer. At Burning Man, this is an unofficial anthem. Ken shakes his head. “Safety first!” he retorts. He points to the 747’s upper deck — the second-story seating pavilion that gave the airbus its notoriety. “Now this is where the cuddle puddle will be.”

What What What Are You Doing

The 747 Project is a large-scale, collaborative art endeavor. Its goal: take a full-size, re-architected Boeing 747 airplane to Burning Man.

The 500+ people involved in the project, all volunteers, some of whom commit every weekend to grueling 10+ hour days in oppressive heat, think this is a good idea. I do too. It’s too crazy not to like.

It’s crazy because the plane is enormous. It weighs 358,000 pounds (179 tons), empty.

Source: © Big Imagination

The plane retired in 2011, after spending ten years as a commercial jetliner and sixteen years ferrying cargo (for a time, to the U.S. Air Force in Germany). Once upon a time, the Boeing 747, with an occupancy of 495 (496 including the captain), democratized air travel for a world eager to earn their wings. Back then, flying filled us with the sense that anything was possible. If we could hurtle through space at 600 mph, what else could we do?

Now, thousands of 747s roam the skies. Planes have become our species’ primary mode of long-distance conveyance. And, thanks to this year’s slate of on-board fiascos and the never-ending sitcom that is the post-9/11 TSA Show, domestic air travel has lost most of its allure. Said otherwise: flying sucks.

The “747 Experience” — our name for the interactive experience inside the plane — trolls the insanity-producing comedy of errors that is flying in the United States. There is an “insecurity checkpoint,” a place to leave your “emotional baggage” and boarding passes on which to write your destination — anywhere in space or time. Could flying be a positive experience? Could it help us shed our fears and connect with one another? Big Imagination, the non-profit supporting the project, thinks so.

At a festival where people go on “trips” of all kinds — metaphysical, psycho-spiritual, drug-fueled, emotional, or simply miles in the sun back to camp — the plane is an irony. A machine supremely articulated to accomplish one thing — fly — turns into another means of transportation, this time, imaginative: where do you want to go?

Source: © Big Imagination

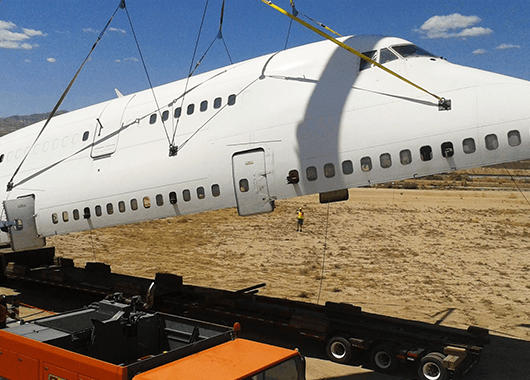

The irony of a grounded airplane pervades the endeavor. The only way to get the 747 to Burning Man (because landing on the playa is forbidden, and local airstrips are too small), is to chop it into pieces. Big pieces. We will cut the fuselage in half lengthwise like a loaf of garlic bread, then cut the top into two transportable half-barrels. After we trim and remove the wings and, (because wind storms churn across the playa, eating unsecured tents and wiping hats off “virgin” Burners’ heads) ditch the plane’s tail, we’ll be ready to go, trucking the plane’s disassembled carcass on huge flatbed trailers over 700 miles north to Nevada. When we reach the playa, we’ll put it back together again, using the structural reinforcements we spent the past two years making, so the deck and wings can safely support hundreds of dancing passengers.

Source: © Big Imagination

But cutting an airplane apart isn’t easy. A plane is an aluminum tube, huge and incredibly light. The tube holds everything in place. It doesn’t like to be cut open.

If it succeeds, the 747 will be the largest moving art installation in Burning Man’s history, if not the largest in the world.

More importantly, it will be absurd. An airplane has no place out there.

“One of the greatest thrills at Burning Man,” writes Jennifer Raiser, author of Burning Man: Art on Fire, “is the first sight of art that should not exist. Art that is too big, too absurd, too breathtaking, to defiant to follow the laws of reason, or gravity, or expectation.”

We are engineering a cosmic joke.

Black Rock Desert | Source: Ikluft/Wikimedia Commons

State of Being

At 9 P.M., volunteers, still in jumpsuits, trickle into the cheekily named “Retreat Center,” a single-story, unassuming home in a subdivision near Mojave. The “RC” sports a living room made of airplane seats, a host of air mattresses, and a garage full of engine parts. Volunteers can sleepover, cook and crash here after a long day working on the plane. Two junior engineers from NASA Jet Propulsion Labs solicit help making dinner. They order helpers around with measuring cups. The chicken comes out perfectly.

We settle into the airplane chairs that make up our living room and someone puts on a black and white Humphrey Bogart film. It’s cold this weekend — windy, as it often is in the high desert — and we have a fire going.

I look around at our ragtag band of volunteers: scientists, airplane mechanics, a fabricator, welder, pilot; space enthusiasts, artists, curious locals, wandering souls, all ages and all walks of life. I think of everyone peripherally involved in this project — hundreds of people in the U.S. and around the world, donating their time or resources (“gifts” of carpet, machinery, LEDs, graphic design); organizing and coordinating from afar.

Why spend all this time and energy resurrecting a dead airplane?

Source: © Big Imagination

The 747 Project has been the focus of much chin-scratching. “Why’s” do not attach easily to its sleek sides. As a writer, I know that an enigmatic “why” is investigatory gold. The question — Why are we doing this? Why are so many people putting their livelihoods on hold to do backbreaking work on a piece of trash in the desert? — is worth asking. And asking again.

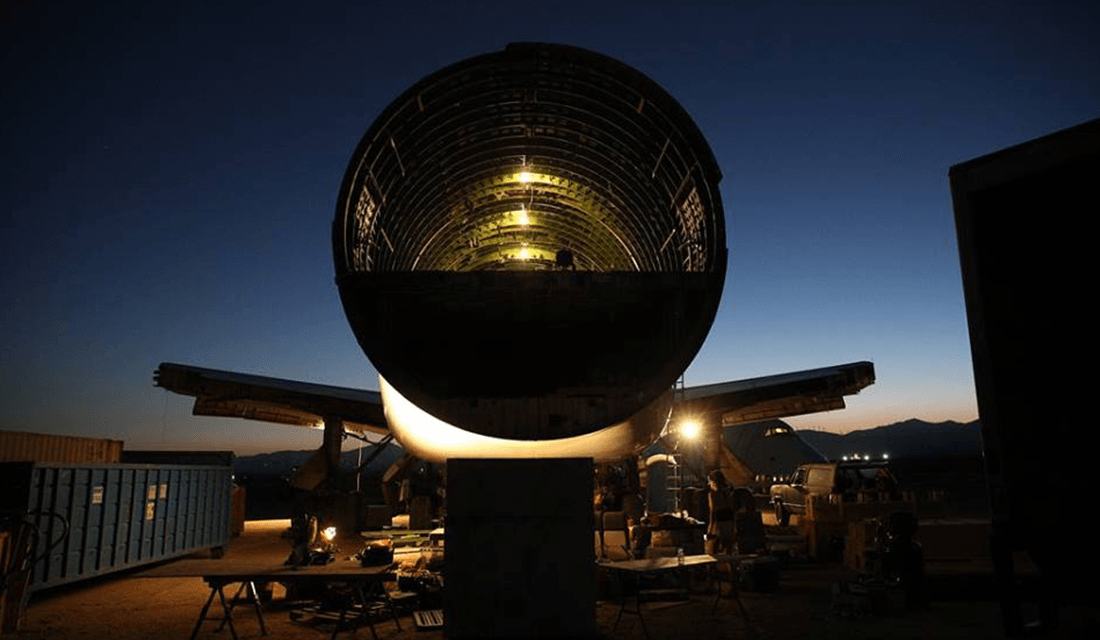

Source: © Big Imagination

I pause from painting benches one weekend to watch our cadre of night shift crew members working inside the fuselage. I’m struck by the poetry of movement in this hard-edged workspace — everyone engaged in their tasks, revolving. It’s a kind of spatial symphony I haven’t felt before. Psychologists would call it group flow. Ancient Greeks had a word for this collective, connected state: ecstasis. Being “stepping beyond oneself” or being in the zone, part of something bigger.

Source: © Big Imagination

Most of us are here to mess around inside an airplane. For master builders, electricians, welders, and engineers, this is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to peel back the skin of one of our greatest-ever flying machines.

I had never used a power tool before stepping foot inside the plane. At first, it was frustrating. The whirring, buzzing drill and I were mortal enemies. But slowly, I got to know it, and then another tool after that. Since stepping off the bus (a school bus) in Mojave in March 2016, I kept coming back. Now, I basically live there. I’ve learned to wield jigsaws and band saws, how to wire outlets and operate a boom lift. I’ve designed furniture, torn out insulation from the plane’s cockpit and cargo bay. I’ve learned how to learn: by doing the thing.

Source: Kelly Vicars and © Big Imagination

This transformed my whole way of thinking. Before long, I had become, have become, an artist.

Art isn’t what you do at Burning Man. Art is what you are.

One volunteer’s life was saved by the plane’s progenitor project, an art car even more outrageous than the rest: a giant pink unicorn with a slide down its butt.

Source: Stephen Greenwood

Art doesn’t need a reason to exist. Absurdist art is an acknowledgment of the inanity that already surrounds us, a reparation for all the time humans have spent hurting one another, wounds sewn by our country in its wars, our collective history of violence. Building something with your hands is repairing. It teaches you how to breathe. Building, fixing, resurrecting a machine — a motorcycle, a circuit board, a human body, a dead airplane – reminds us that things do compute; things do connect; but often we have to fix them. Running a “machine,” as Robert M. Pirsig puts it, isn’t always a button we press. We must learn how the machine actually works.

Large-scale, inclusive art projects license experimental creativity and non-judgmental learning. In our hyper-individualist, productivity-obsessed culture, this is a revelation. “There’s no ego in it,” Sofia says. We’re holding ladders for one another.”

Something Ablaze

The spark that sent the first Man up in flames has ignited a bigger fire than anyone anticipated. It has launched an artistic culture that is vibrant, participatory, and — through regional Burns and Burner-led initiatives in hundreds of countries — making its way around the globe.

Burning Man 2015 | Source: Max Talbot-Minkin/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

As its notoriety grows, so do questions of what it will become. Can Burning Man maintain its hyper-creative, survivalist ethos through a coming generational hand-off? Will the 10 Principles survive? Or will its popularity bring it mainstream and zap the “counter” from the counter-culture fest? It Burning Man dead?

This is a worst-case scenario. Burners like to plan for that.

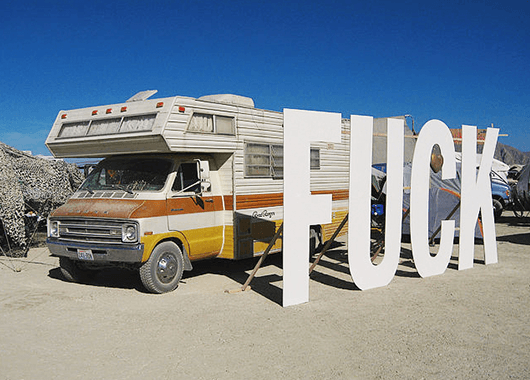

Chief among these concerns is the fear that the festival is being overrun by corporate, moneyed excess. Cut to: post-apocalyptic desert tundra: Silicon Valley CEOs jet into their annual networking shindig (I say, good luck making out Steve Wozniak in a dust storm in a toga) and spend tens of thousands of dollars to recline in their air-conditioned RV villages, get drunk, get high, eat sushi, and peace out, leaving in their wake a trail of sequiny, sparkly MOOP (Burning Man’s acronym for trash: matter out of place). These cloistered royals raise a giant “fuck you” to Principle number four: Radical Self-Reliance.

I share the fear that VIP status, exclusivity, and Instagram may undermine the wild spirit of resourcefulness, the fuck-all attitude that birthed Burning Man’s experiential economy: an economy powered NOT by corporate lust or consumer greed but by something that beats far wider and far deeper: a vital version of our humanity, kind and self-reliant, that survives, and thrives, in the unlikeliest of places.

But what threatens this spirit isn’t money, per se. It’s the threat of the “private” — the idea that experience can be bought, inherited, bartered, sold.

To this, Burning Man says: FUCK OFF, capitalism!

It is rash to conflate the (old, not new) ever-lurking danger of the private with the existence of wealth at Burning Man. Many participants who camp in style are entrepreneurs who subscribe to Burning Man’s sacred tenet: if you have a wild idea, make it happen. The founders called this a “do-ocracy.”

If we were to reduce Burning Man down to its essence, its eau-de-vie… I think we might find ourselves on a June night at San Francisco in 1986. Larry Harvey has a crazy idea for a project to build with his son. He and his friend Jerry James find some firewood, knock together a wooden figure and drag it to Baker Beach. They light it up, and a crowd gathers to watch it burn.

Raising the first Man on Baker Beach | Source: Dan Miller/Burning Man Journal

What they didn’t do: laugh off the idea. That night, they danced on the beach, embers burning. It turns out we all have something to say goodbye to. It was a new rendition of an old thing: destruction makes way for creation. The man could be whoever, whatever you wanted.

This is the spirit of Burning Man.

“Creativity loves courage,” says New York-based Burning Man sculptor and metalworker Kate Raudenbush. “Do not let the fear of the unknown stop you from the act of creating. Keep your mind set on maximum curiosity and minimum wasting of time.”

Burning Man grants us permission to experiment, to learn, to create, and to DO, bravely.

Because Survival is Not Enough

Running through the wind and sun-parched sand of Mojave’s wind-turbine spiked valley, I marvel at the scrub brush and cacti, their twisted branches and dagger-like tines. More than the budding wonders of my Bay Area home, these plants display nature’s strict imperative to grow. In so raw a place, what comes to life must be creative and must possess guile if it is to survive. Near-translucent lizards with black spots. Joshua trees, sprung from ancient coral. There is something about this environment that gives birth to things weird, beautiful, even holy. In the desert, the creative spirit pulses brazenly.

Mojave Desert | Source: Renette Stowe/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

We all have big ideas, but only some of us entertain them.

The plane found Ken Feldman, and Ken found the rest of us, hundreds of people around the world who are boarding an un-flying airplane, because, why? Because some ideas just want to be born.

Because: why not?

Source: © Big Imagination