RIZAL IWAN

A few years ago, together with several other members of the Jakarta Players, I sat down for a first read of our next production, An Inspector Calls, J. B. Priestley’s whodunit mystery centered around a British family, the Birlings.

After we finished the read, Michael, our director, did a little table work and asked what each of us thought the play was about. Our answers varied: A murder. A social commentary on the power struggle between the have and the have not. A dysfunctional family drama masked as a mystery. One even said a ghost story, referring to the inexplicable existence of the titular Inspector. Then, John, one of the cast members, came up with an answer that stood out from the rest, “I think it’s about adoption.”

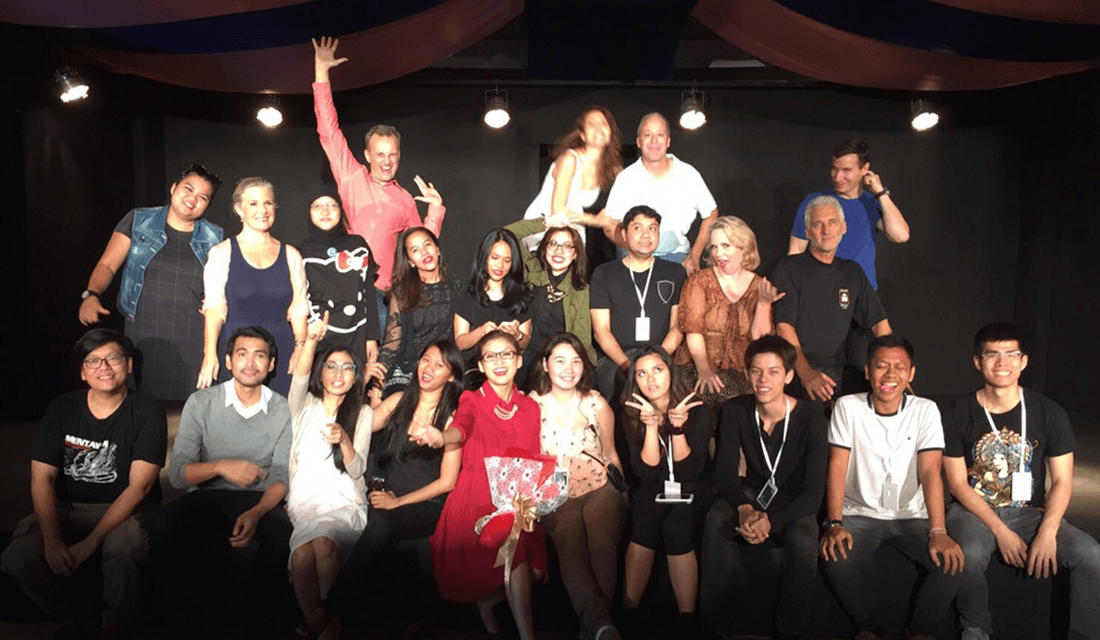

The answer was meant as a joke, of course, and was irrelevant to the text, but we all knew right away what he was poking fun at. We looked around the table and found that — in the very familiar tradition of the Jakarta Players — our circle was comprised of a balanced mix of Indonesians and non-Indonesians. The producer was American, the director was British, and the small cast was a motley crew of Indonesians, an American, a Canadian, and a Dutch.

Cast of Jakarta Players’ 2013 production of An Inspector Calls | Source: Jakarta Players

The Birling family couldn’t look more different from one another. John the American and Gene the Canadian — both Caucasians — played the parents, while Soraya and I — both dark-skinned Indonesians — played the family’s children.

We all laughed at the joke, and none of us thought it was a big deal, as we continued with the table read discussion, and John gave us his answer of what he really thought the play was about. However, this brief moment of intermission humor stayed with me for a long time after — and kept coming back to me throughout my experience of being a performer for a company like the Jakarta Players.

Jakarta Players Presents – An Inspector Calls (@america) | Source: Heriska Suthapa/YouTube

The Stateless Players

First, a little glimpse of the Jakarta Players.

The Jakarta Players is a community theatre group in Jakarta, Indonesia, which produces English-language plays. It has been around since 1968, and has staged all types of shows; from dark psychological thrillers (Ira Levin’s Veronica’s Room) to absurd farces (Christopher Durang’s Beyond Therapy), from the crowd-pleasing (Mike Folie’s Naked Mole Rats in the World of Darkness) to the mind-bending (Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice).

Cast and crew of Jakarta Players’ 2015 production of Naked Mole Rats in the Heart of Darkness | Source: Jakarta Players/Facebook

In the beginning, the group reached out to Jakarta’s expatriate community, providing a creative outlet for people of different nationalities, backgrounds, and occupations; as well as an answer for audiences who seek out English-language entertainment for a night about town. Each year, more Indonesians join the Jakarta Players, dipping our toes into performing in English, and turning the company into the city’s theatrical melting pot. Some see it as a novelty, some as a challenge, and some simply feel more comfortable acting in English, having been growing up with the inevitable exposure to American films, TV shows, and popular culture.

So what the audience would see when they are watching An Inspector Calls — a family of white parents and Asian kids, playing a British family with assorted accents — is not an uncommon sight for the Jakarta Players crowd. On stage, we are stateless.

We never see this as a problem, of course. In fact, it is something that we celebrate. Trading stories, cultural references, and notes with people from different countries and backgrounds is what makes the Jakarta Players experience so unique and precious. We all have our own reasons:

This is what makes our shows more fun!

No barriers, everyone can be anyone.

As long as the plays and the performances are engaging enough, the audience will not mind.

This is theatre, where suspension of disbelief is the rule of logic.

But, as I was sitting in the middle of a rehearsal, or waiting for my cue, questions would sometimes come back into my head. As much as I enjoy working in this diverse environment, how does a diverse cast impact the play’s reception? Can we expect the audience to fully succumb to this total suspension of disbelief? Can the play survive this array of different nationalities among the cast, as well as among the audience? What will it do to the dynamic between the performers and the audience?

As I came to find out along the way, it calls for a little process of adaptation… and not at all in the way that I’d had in mind.

Thus, we, the performers, in our detachment from any specific nationality, can also be agents of adaptation.

Adaptation Beyond Words

When we hear the word “adaptation” in theatre, the first thing that comes to mind mostly has something to do with the text — whether it’s from one language to another, from one setting to another, or even from one medium to another.

I used to think that the type of work we do with the Jakarta Players is not included within the sphere of adaptation, because we are mostly doing plays in the language, context, and setting in which they were originally written.

I came to find out, however, that while the text itself may not be adapted, there are other types of adaptation; ways to get the message of the play across — intact — from our multicultural production team to our multicultural audience.

Like the many people joining the Jakarta Players’ productions, the audiences for our shows are also getting more diverse. It’s easy to imagine that back in their early days, the Jakarta Players’ audiences were predominantly non-Indonesians. However, we have had more and more Indonesians in the audience, and, as recent shows testified, we have been playing to predominantly Indonesian crowds.

Thus, a challenge presents itself: how to make the audience connect more with a material that sometimes is so far flung from their culture, frame of references, and everyday lives. This process starts as early as a board meeting, where the Jakarta Players board members are choosing which play they are going to produce next. But even after they pick the right play, the people involved in the production are still faced with the task of making that material come alive for the audience.

Jakarta Players Presents: Status: It’s Complicated! | Source: © Jakarta Globe/YouTube

Sometimes a play’s text is so engaging and universal that it connects effortlessly with the audience. Naked Mole Rats in the World of Darkness, for example, was a big hit thanks to its universal theme of he says/she says (and a healthy dose of physical comedy).

As for An Inspector Calls, John’s adoption joke at our first read remained an inside joke among the cast and crew, because it turned out people were not even noticing how the Birlings have such curiously dark-skinned children. They were so engrossed in the even more pressing question that is: who killed Eva Smith?

Even a friend of mine who doesn’t particularly enjoy theatre — let alone in English — stayed awake through the three-act talk fest and enjoyed the whole “Agatha Christie-like plot.” (Of course, there are always nitpicky audience members, who would come up to me after the show and said things like: “You guys should have chosen a different table cloth!” or “But you and Soraya don’t look alike, how can you be brother and sister?” — to which I stared back incredulously with an expression that said, “Really? That’s your issue with the casting choice?”)

Even the audience has to do a little adaptation of their own, in watching the play. They need to adjust their suspension of disbelief and set it to a slightly higher level. So at the end, they will be able to embrace our statelessness, go beyond the physical, and see the characters as what they are inside.

However, some plays are so rich with local references that the production team had to take extra efforts not to lose the audience. Despite its lightweight fun, relatable characters, and easy-to-follow plot, Christopher Durang’s Beyond Therapy is so heavily ridden with American slangs and pop culture references (from the 1980’s, no less), that even the cast got lost during rehearsals — one actor delivered a line about David Berkowitz romantically, thinking he was a heartthrob actor from the 1980’s, before we learned later that he was actually an infamous serial killer!

To make sure our audience stays with us and is not missing out on the jokes, the production team came up with the idea of including a mini “glossary” in the program book, to explain what Plato’s Retreat is, or who Marie of Romania was, for example.

At other times, we find that a character or a performance can also be adapted as a device to connect to our Indonesian audience. Thus, we, the performers, in our detachment from any specific nationality, can also be agents of adaptation.

Jakarta Players’ 2013 production of Godspell | Source: Jakarta Players/Facebook

In a production of Godspell, one actor got non-stop laughs simply because she chose to deliver her English lines in a thick Indonesian accent, turning her otherwise harmless lines into comedic weapons, and making her character stand out in the ensemble piece, thus totally engaging with the audience.

Furthermore, I discovered how, as an actor, our statelessness can also affect our relationship with the character we are playing.

At first, I thought being an Indonesian performing an English-language play could be confusing or confining. When I first started out with the Jakarta Players, I thought that in performing an American play, or playing an American character, you’d have to look or sound as American as possible. But what I discovered along the way is that being in a multinational theatre company like the Jakarta Players can, in fact, give us more freedom as a performer, to explore, enrich, and play around with our characters.

Jakarta Players Community Theater Troupe to Put on ‘Circle Mirror Transformation’ | Source: © Jakarta Globe/YouTube

Cast of Jakarta Players’ 2012 production of Twelve Angry Men | Source: Jakarta Players

I got the first glimpse of this discovery during our production of Reginald Rose’s Twelve Angry Men – my first production with the Jakarta Players. Aside from the text, the production itself was already some sort of an adaptation, because, instead of an all-male cast, we had six male and six female actors playing the jurors — again, with a balanced mix of Indonesians and non-Indonesians. I didn’t realize it at the time, but despite being completely faithful to the text, this change has already granted us a liberty with the characters we were playing.

In a conversation with Grace, a fellow cast member who played Juror #2, as we waited around for the stage to be set up during one of the rehearsals, she told me that she had made up a whole backstory for her character. In her mind, she was an Asian-American woman, with an elaborate invented background. She used this to interpret her character, and that was how she motivated her performance.

I remember thinking to myself: were we allowed to do that? But of course we were. This production had already taken a liberty with the gender of the characters, so why not make further explorations? No one said we had to replicate the twelve male, white Americans, which I remembered from the 1957 movie version (at the time, my only source of reference).

This conversation with Grace changed the way I saw what performing with an English text would be like. Instead of seeing the difference between myself and the culture or context in which the text was created as an obstacle, I realized we could just capitalize on it, by exploring our characters in a different way, breathing a new life into it.

The audience may or may not see this, but it is such an interesting way to approach and develop a relationship with our character. If it becomes tangible and the audience feels it, that’s great. But if not, it can just be a precious little secret between you and your character.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but despite being completely faithful to the text, this change has already granted us a liberty with the characters we were playing.

That night of the first read of An Inspector Calls, as we were wrapping up, I came up to John and asked him about the adoption joke, “Do you think the audience will get distracted?”

He gave me a look I couldn’t quite decode, perhaps saying I was reading too much into things. But I eventually got the answer to my own question.

Jakarta Players’ 2011 production of The Government Inspector | Source: Jakarta Players/Facebook

In such a diverse theatrical ecosystem like the Jakarta Players, everyone needs to adapt. Even the audience has to do a little adaptation of their own, in watching the play. They need to adjust their suspension of disbelief and set it to a slightly higher level. So at the end, they will be able to embrace our statelessness, go beyond the physical, and see the characters as what they are inside.

All we can do, as performers, is try our very best to make their adaptation process as easy as possible.

What I discovered along the way is that being in a multinational theatre company like the Jakarta Players can, in fact, give us more freedom as a performer, to explore, enrich, and play around with our characters.

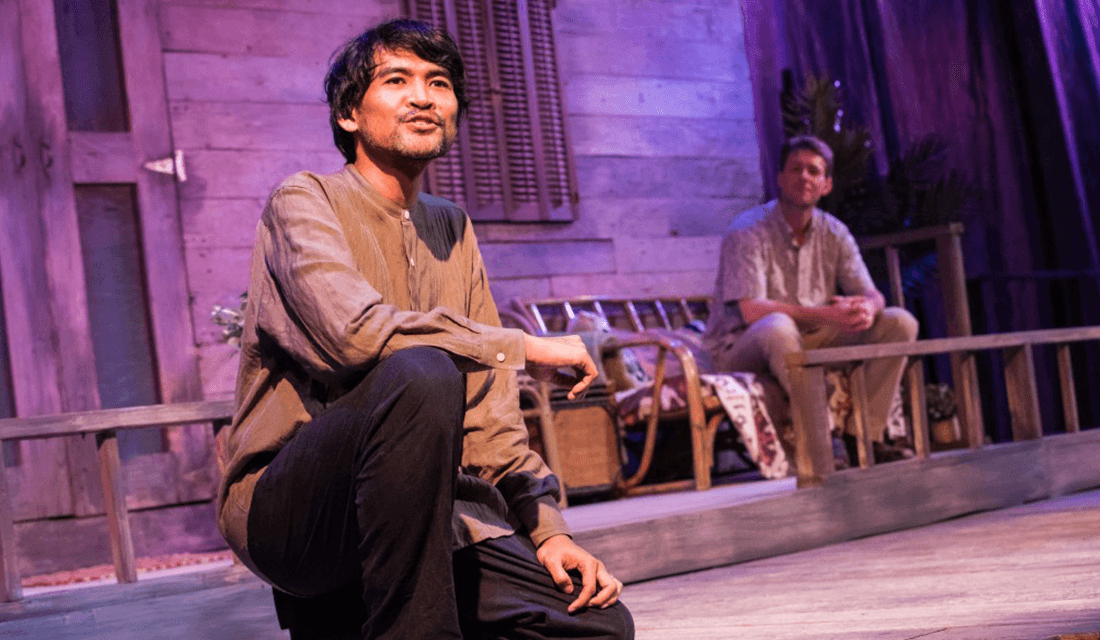

In the spring of 2017, I was lucky enough to be involved in Rorschach Theatre’s production of Forgotten Kingdoms, a play by Randy Baker, in Washington, D.C.

Debut Rizal Iwan Dalam Teater “Forgotten Kingdoms” | Source: © VOA Indonesia/YouTube

For once, I was on the other end of the spectrum. I was playing an Indonesian character to predominantly American audiences. And I remember dealing with a different kind of adaptation from my side.

Instead of adapting to a character that is not my nationality, this time the adaptation process took place mostly off stage, as I was getting used to a different routine of rehearsals and shows — an intense 5-week rehearsal time for a 5-week run, 4 shows a week; as opposed to what I had been used to with the Jakarta Players community theatre: a laid back, 3-month long rehearsal time for a 3-day run over the weekend.

In one of our dressing room chats with my fellow cast members, as we were getting into our costumes and waiting for the house to open, my castmate Sun King Davis asked me, “So back in Indonesia, did you ever do adaptations? Say, an Indonesian version of Death of a Salesman, or something like that?”

My answer at the time was an immediate “no”, because I had never done it with the Jakarta Players. The text always remains in its original form.

However, come to think of it now, Sun King’s simple question would not have been met with a simple answer. With a stateless theatre company like the Jakarta Players, performing to an equally diverse audiences, we never alter the text, but we also never stop adapting.

Rizal Iwan as Yusuf in Rorschach Theatre’s 2017 production of Forgotten Kingdoms | Source: © DJ Corey Photography/Rorschach Theatre