KELLEY KIDD

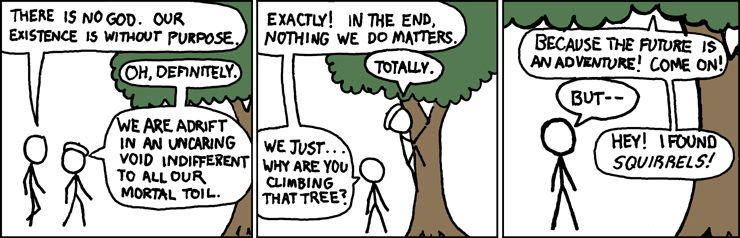

Popular webcomic XKCD | Source: XKCD (CC-BY-NC-2.5)

Where the butterfly lands might change the course of natural order | Source: Missouri State Archives/Flickr

Sometimes, things don’t go the way we expect them to go. Due to limitations on our capacity as humans to see the big picture, events we might have previously considered unthinkable come to pass on a regular basis and with significant impact. Small, seemingly random events impact one another in wildly significant and unpredictable ways. The vast and unpredictable nature of the universe — and the sequences of cause and effect that exist beyond what we can even begin to imagine — looks like chaos from the human viewpoint. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it, “The big news about chaos is supposed to be that the smallest of changes in a system can result in very large differences in that system’s behavior. The so-called butterfly effect has become one of the most popular images of chaos.” The smallest of movements can create massive, unpredictable impact, and our existence is subject to these vast forces beyond our individual control. On the one hand, this leaves us with a sense that the consequences of our actions may be far beyond what we can foresee. On the other, though, we feel as though we are at the mercy of unending randomness and uncertainty. The amount beyond the scope of our perception and control is infinite, yet we are active participants in the world. Confronted with a universe of chaos in which our actions get lost in the vastness, but in which we are nonetheless forced to act, we as humans have constructed numerous ways to feel comfortable.

We as humans find ourselves facing a sense of radical freedom in our choices. We must therefore constantly assess and choose who and how to be in the world, which is an enormous undertaking without any sense of external guidance.

We try to create order around the chaos, to paint an understanding onto it, or fit it into a box — to make sense of our place within it. In order to effectively allow humans to grapple with the vastness and apparent disorder of the chaos, a structure must offer a framework with which to make decisions, some sense of meaning, and motivation to continue living. Both religion and philosophy offer narratives equipped with these tools for framing the chaos of existence.

Decision Making in the Face of Chaos

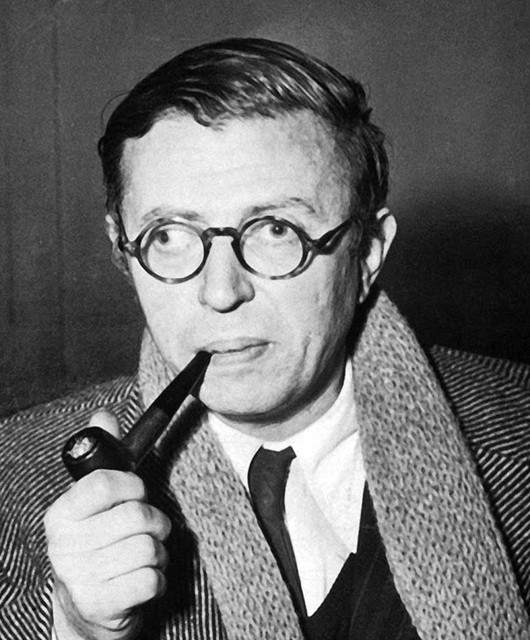

Jean-Paul Sartre | Source: Quotesgram.com

The idea of the butterfly effect can be paralyzing, as it makes weighing the consequences of a decision impossible. Existentialist French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre described this fear of the power of our own choices as “radical freedom.” He posited that this is so frightening because, “in contrast to other entities — whose essential properties are fixed by the kind of entities they are — what is essential to a human being — what makes her who she is — is not fixed by her type but by what she makes of herself, who she becomes.” In other words, in his view, humans have no inherent selves beyond the person they act out in the world. We have total control over every choice; in fact, we are “condemned to be free” because radical freedom forces us to be responsible for every action we take. Faced with choices of this import, we turn to religion and philosophy to help guide us in the face of decision-making by helping us better comprehend the options available to us and where they might lead, or at least how to approach selecting from among them.

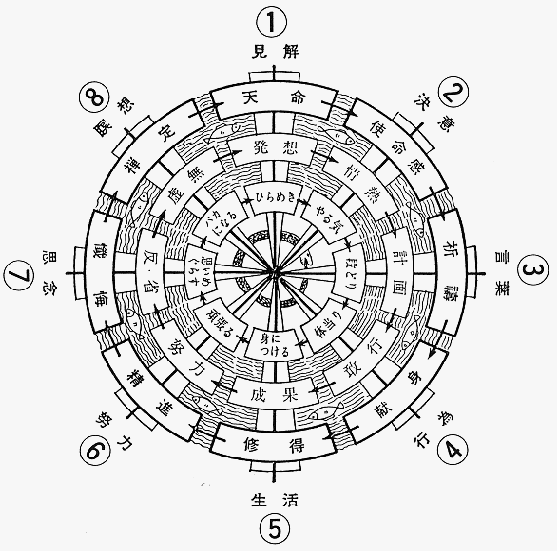

The Noble Eightfold Path: 1) Right View, 2) Right Resolve/Intention, 3) Right Speech, 4) Right Conduct/Action, 5) Right Livelihood, 6) Right Effort, 7) Right Mindfulness, 8) Right Meditation/Concentration | Source: Buddhanet

Most simply, religion often offers participants a structured moral code against which they can assess their choices, complete with a built-in set of consequences for each type of action. Mythologies present examples of different options of behavior and associate them with results. Christian parables, for instance, serve as complete metaphors with messages for the listener. The path to righteousness is all but tied up in a neat little bow. Some faiths offer philosophies of action, such Buddhism’s Noble Eightfold Path. Faith in a higher power also allows participants in religion to put trust in an external guiding force, which offers relief from the terror associated with total freedom. Prayer and faith provide many believers with a sense of trust in their actions as they put trust in some form of God to guide their decision-making. While free will may or may not exist and different religions may struggle with this question in different ways (including considering whether chaos itself is a creation of God or humanity), most conceive of the god-like figure as a guide, mythology as tools for teaching, and prayer as a way for seeking guidance and accessing wisdom greater than that of the individual.

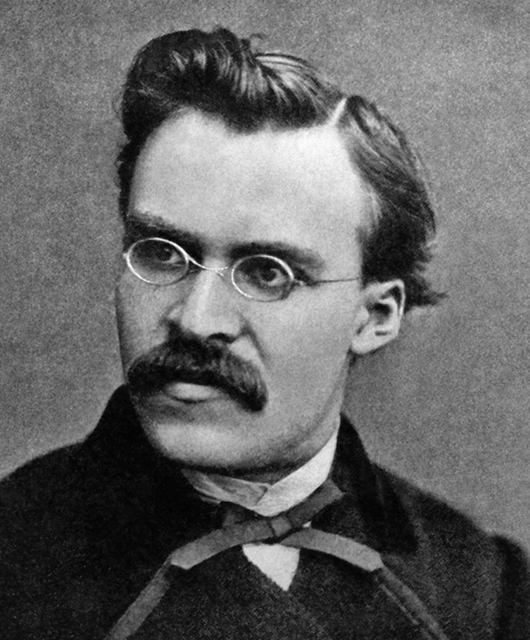

Friedrich Nietzsche | Source: Wikimedia Commons

However, science has brought us to a place whereby a wholehearted belief in an omnipotent or omniscient being is more challenging to hold. Once the idea of a God — or some external omnipotent ordering force — is removed, we are left with just the individual experience within the vastness. Right and wrong become much fuzzier, and decision-making becomes less clear cut. The only confining structures on an individual’s choices are the social norms surrounding them, which rest on unsteady ground. We as humans find ourselves facing a sense of radical freedom in our choices. We must therefore constantly assess and choose who and how to be in the world, which is an enormous undertaking without any sense of external guidance. A major feature of the “existentialist outlook is the idea that we spend much of lives devising strategies for denying or evading the anguish of freedom,” when nothing external provides “substantive norms for existing […] that specify particular ways of life.”

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche strived to address precisely this question in the face of “the consequences of the death of God […] the collapse of any theistic support for morality.” He saw this as an opportunity to take personal responsibility for autonomy. In order to do so, though, one must take responsibility for generating a sense of meaning for oneself.

Confronted with a universe of chaos in which our actions get lost in the vastness, but in which we are nonetheless forced to act, we as humans have constructed numerous ways to feel comfortable.

Finding Meaning in the Face of Meaninglessness

In the face of the vastness of the universe and the sense of infinitude beyond oneself, the first thing to go is one’s sense of worth. As tiny features of a world where so much is beyond our control, we can find ourselves afraid of our own meaninglessness against this backdrop.

Religion presents numerous options to help participants find meaning in their daily lives. Practically speaking, religious community provides support, a sense of home and belonging, and authentic supportive connection. Mythology — or “collective dreams” as Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carl Jung described them — connects the struggle of the individual to that of humanity as a whole. Mythology allows for validation of the individual human struggle through connection to others, both present tense and historical. Myth and spiritual study leads people to connection with a historical lineage, a higher power, and a community — all of which infuse life with a sense of connectedness. This connection allows for individuals to feel like part of a greater web, rather than an isolated speck in a distant cold universe. Mythology and religious institutions also provide narrative structures which we can use to frame our lives. As I’ve touched on in a past piece, the existence of a narrative through which we can view our own characters significantly impacts people’s sense of place and well-being in the world.

A relief on the Borobudur temple in Indonesia | Source: Michael Gunter/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

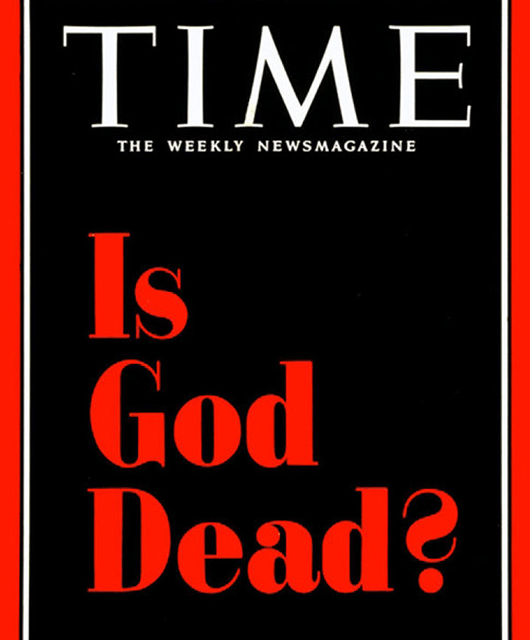

The iconic and controversial TIME magazine cover on April 8, 1966 | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Religion provides a sense of belonging and a place of value in the universe, usually by connecting human existence to the will of some higher power. It constructs an ordered narrative around the chaos, and often also promises unconditional love from that higher power, which allows people to have an unwavering source of worth in the universe. Religion tends to present the image of the higher power as one who is directly interested in and involved with the lives of participants. Participants are able to believe that there is a plan beyond what they can see or know and that they play a role in that bigger picture; to be able to frame all that comes to pass — whether positive or negative — in light of a narrative greater than oneself allows for freedom from the anxiety of existence. When an active, participatory, loving God is part of the picture, it becomes much easier to answer questions of why we exist and whether our lives hold meaning.

However, without God in the picture, philosophers were confronted with the task of considering what humans could do to create a sense of meaning in their lives significant enough to shape their decisions.

In the face of the vastness of the universe and the sense of infinitude beyond oneself, the first thing to go is one’s sense of worth.

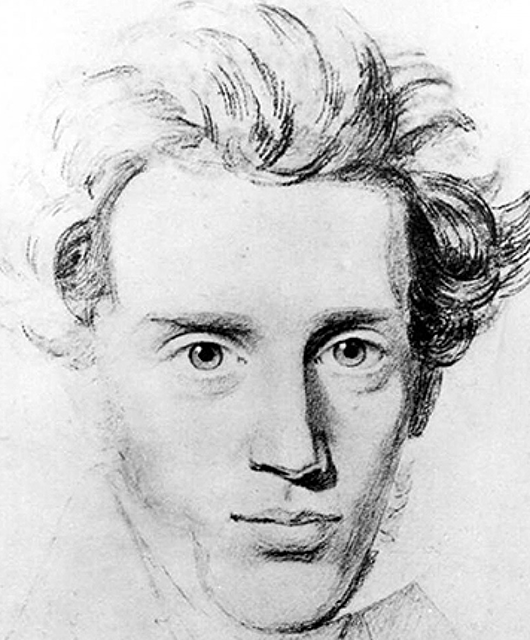

Søren Kierkegaard | Source: © Lapham’s Quarterly

Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard argued for a guiding sense much like that of a religious connection. He posited that life holds meaning when “[I] raise myself to the universal,” connecting to what feels absolute to him. He acknowledged that this experience is a subjective one, rather than an absolute objective connection. However, he argued that to adhere to norms of society or religion for their own sake is in a way not to connect to meaning. Rather, he made the case to create one’s own norms by turning deeply inward to seek them, thus releasing reason and embracing the paradoxical subjective sense of the absolute. In this way, he argued, “I ‘truly’ become what I nominally already am […] truth measures the attitude (“passion”) with which I appropriate, or make my own, an “objective uncertainty” (the voice of God) in a ‘process of highest inwardness.’” He was the first to make the case for the subjective as the “truth” — the experience towards which we should orient in seeking meaning and answers.

People find and create beauty, love, and joy within the chaos, meaninglessness be damned.

Nietzsche followed suit in encouraging individuals to utilize their autonomy to take responsibility for creating meaning. Faced with the meaninglessness of nihilism, he takes “its life-denying essence,” and he reconfigures the moral idea of autonomy so as to “release the life-affirming potential within it.” He saw — in a world where all “transcendent supports” had given way — the opportunity to create for oneself a code of action. Within that, he felt a sense of freedom and empowerment to sift through one’s impulses “according to a unifying sensibility, a ruling instinct, that brings everything into a whole.” We have the capacity to establish our own code and sense of importance, through which we can sort our experiences and desires in order to make choices in the way that feels most right to us.

Existentialism consistently holds authenticity at the core of this self-created code. What Nietzsche is describing is not simply acting on impulses or reacting by whatever feels good in the moment. Authenticity describes an integrity and a commitment to the self that one chooses to be. For some, this might even mean committing to a narrative, which results in a framework similar to that created by participation in religion. This authenticity allows one to trust that decisions do derive from values; that there is a sense of something imagined that is still greater than ‘me,’ so that my behavior is not simply self-serving or disengaged. In fact, authentic action is rooted in a commitment to a deeply rooted sense of self — much like the “highest inwardness” described by Kierkegaard. On the other hand, “the inauthentic life would be one without such integrity, one in which I allow my life-story to be dictated by the world,” as philosopher Steven Crowell pointed out. This is the difference between acting because of “should” and because it is who I have chosen to be in the world.

Why Bother?

Within this process, there remains an anxiety surrounding the ‘why’ beneath all of these questions. Absurdism acknowledges how many of our assumptions are taken for granted, despite having no ultimate foundation. Reason, value, and meaning “have a foothold in the world [yet] they are not intrinsic to being, and at some point reasons give out.” Looking past those reasons, all that remains is the existence and layers of ‘foundationless’ explanation — people desperately seeking and creating meaning where there may be none.

So, how do we seek something to live for?

Some argue for diversion, some for hope, and some for freedom from the attempt to create meaning at all.

Religion provides structure, ritual, and community. This may be considered to be diversion. However, ritual also seems to allow access to some form of ecstasy, escape from the limitations of self, and a sense of being part of either the vast something or the vast nothing. The performance of ritual brings access to what lies beyond the self, which provides some relief from the terror of meaninglessness, because it removes some of the self-absorption. Connecting to, or being part of, either a nothing or a something greater makes the meaninglessness of an individual life less frightening because it renders the existence of meaning in the individual life less of the point of life itself — it takes some of the pressure off, if you will.

The existence of a narrative through which we can view our own characters significantly impacts people’s sense of place and well-being in the world.

Source: Florida Memory/Flickr

Hope lies in the knowledge that, with ultimate freedom and a landscape where nothing is truly determined, we have the freedom to change our actions at any time. The options available to us are unlimited, and perhaps we can have some impact on the chaos if our actions have as much impact as a butterfly’s wings. In a surprisingly uplifting quote, Nietzsche once offered that “one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.” People find and create beauty, love, and joy within the chaos, meaninglessness be damned.

This hope seems connected to a freedom from the attempt to create meaning at all. As illustrated at the beginning of this piece — my favorite XKCD comic of all time — the embrace of the absurd offers a remarkable freedom to have hope, to play in the chaos, and to find relief in the nihilism.

Katie Bellamy Mitchell assisted with the content of this piece.