CAROLINE BAUWENS

In the thick, stagnant air of Brooklyn, a group of people congregate. It is 7 P.M., but designated leaders have here since at least 6:45 P.M. Anticipation and sweat percolate. People are dressed in the called-for attire: all black. Everyone wears a mask; we are still in a pandemic.

We walk and stop every so often at different makeshift stages to listen. A mid marker. A sidewalk. Steps in front of a department store, whose windows are boarded-up. The cement stand of a traffic light. In lieu of available platforms, we kneel and let the words of the centrifuge carry over the tops of our heads, flowing through the group, carried by the crowd repeating the speaker’s words in waves.

Our audiences are there, always. They stand at their balconies and cheer, but not once do any of them come down from their renovated studio apartments to join on foot. The distance that separates them and us is wider than the sidewalk and stoops of their brownstones, made wider still by varying degrees of individual positions. To cross through this distance would engender a political ethos that this audience feels no strong enough inclination to adopt, just one strong enough to rally for and tape neat calligraphic signs to their windows that will stay there for weeks and slowly fade in the summer sun. This is the Brooklyn that is most likely still employed, evident their maintenance of a proper quotidian schedule, if not in the background blue glow of their work computers propped on makeshift standing desks of stacked Phaidon interior design books, or their palpable ease at not having to rely on the slippery eel that is the New York State Department of Labor. This audience never sweats in New York summers, they have Whole Foods incomes, they own their own online domains, and have engaging conversations with their spouses about the trials and tribulations of raising a feminist child in a gender-neutral environment. They stay comfortable behind their doors, their windows, their homes that, just a decade ago, housed a very different demographic — without AC.

The other audience is more engaging. They have left their confines and followed us on foot, or by car. We must be a real show because one night, they outnumber us at least 4 to 1. This audience is silent. They are content to watch and wait and the distance separating us is porous and prone to dissolving should anything cross between. When they move, they move deliberately and with precision, as if responding to some call heard only by them. We are alert to their reaction to us, but carry on for the most part as we intend to. Not entirely unfazed, but resolute. On the first night of the second month of protests, the 11 P.M. curfew instills a greater sense of urgency, but redirects the energy in a way that feels disparaging: we are now not just out here to protest, but we are out here to be able to be out here. The end of each night is a conscious decision: either someone removes you or you remove yourself.

No one is looking for me, I have only myself to account for and no one will notice if I get knocked down or taken away.

At the end of these nights, when I separate myself from the organism and head back down Greene, or Atlantic, or take the C if I’ve made it as far as Manhattan, I feel and unshakable sense of relief and guilt. I think of the number of protestors arrested on their way home and I know that if I just ditch my cardboard behind some trash, I could melt into my surroundings and my whiteness. To assuage the guilt, I tell myself that I am Different with Standards and I will own up, proudly, to my whereabouts of the evening in case I do get stopped. However, a few blocks from home one night, my innards crumble when two cops walk briskly in my direction and my immediate reaction is to ditch the sign, don an unsuspecting demeanor, and bat my eyelashes. A few seconds later, the cops have materialized in a street light as just two burly men and I am left anxious and alone to contend with the empty confines of my gut.

Sometimes I am with friends, and the rudimentary comfort of having a buddy whose presence I may rely upon in the crowd as we walk miles throughout the city is a comfort I have not forgotten since elementary school field trips. The thrill of companionship is alive again now that many of us spend our days alone, akin to the unspoken but shared sense of complicity when leaving a classroom with someone, as in I can’t believe we get to go off together. Other times I go alone, and it is then that I feel “myself,” in the ontological sense of the word, melt into the compound organism of collective bodies. No one is looking for me, I have only myself to account for and no one will notice if I get knocked down or taken away. It is these times that I stay out the latest, push to the front, put my body between others. Several nights in a row I see the same couple, and on the third night one of them notices me staring at her girlfriend a little too long and locks me into a staring contest which, if she had been a man, I would have competitively stepped up to, but in truth I just admire them as a couple and envy the way their bodies fit together like puzzle pieces and how they seem to be so coordinated in their monochrome outfits and socio-political views in a way that is not redundant but mutually elevating. So, I crinkle my eyes in the cursory signal of I Am Harmless and look forward towards the police blockade in front of the Brooklyn Bridge.

A week later I am sitting in the park reading and I see the couple, celebrating a birthday. They are in polychrome outfits and I see their mask-less faces from a distance. I recognize them from their body language in how the one I stared at moves towards the one who stared at me and hugs her from the side before kissing her neck. This is an intimate gesture, a happy gesture, but also the same gesture she expressed a few protests ago somewhere along Atlantic listening to a woman describe losing her son. The boy had died at 16 — the same age the woman’s brother had been when arrested for walking home while black one night after work, she tells us. Between the woman’s soft cries and the silence of the city, nestled between bodies and in the light of street lamps, I saw this gesture. Seeing it in the park now makes me wonder what it must be like to be so in tune, even briefly, with another person, your emotions, your place in the social order of the world that you are able to exist, self-preserved, in the full spectrum of your emotions with someone else. It is a power in itself, I think, and keep on reading.

I haven’t seen the couple in some days, and I miss them. The temperature these days has been putrid and drenching, and a woman in a pink tank top is walking in front of me with a sign that reads: “Yeah sex is good, but have u ever fucked the system,” in big pink bubble letters on a lighter pink background. The letters are running and faded and the cardboard is bent in different areas. She had this sign a few days ago when I first saw her at Grand Army Plaza; her friend, who had been carrying a papier-mâché pig-cop head, walked from the Plaza all the way to Manhattan with a cast on her foot that day. The friend, now sans pig-cop head, is also sans cast but holds a crisp purple sign that makes me feel that I would love to be their friend so they might invite me to their sign-making activities and drink wine in their apartment, which I imagine is an open-floor studio teeming with plants and series of abstract modern art with punchy colors and a stocked library of books we would discuss: Kimberlé Crenshaw and intersectional feminism, or Judith Butler and radical hope. Is it silly to make friends at a protest? Attending to social inclinations here feels as blasphemous as working out in a cemetery, but where better to assuage the feeling of pandemic-imposed isolation? Just a week prior, while marching through downtown Brooklyn, I recognized a colleague for whom I worked before the pandemic and, for the briefest moment, weighed the option of approaching him. When he would email me about a potential job soon after our near reunion, I tried to decipher between his lines any recognition on his end. Could “I hope you’re well” be coded for “If you’re reading this, you must not be in a holding cell, and for that I am quite relieved”?

One afternoon I am walking in Bushwick. On Himrod and Central a fire hydrant is open and gushing water. A lawn chair placed over the hole spews the water in every direction and two little boys are running through the fountain and laughing. Cars pass often, but the boys don’t seem to mind, or notice. The smallest throws a ball for their dog to catch and the dog does not catch it. The boys watch as the dog trots in the general direction of the ball before stopping, apparently suddenly bored in his expedition, and turns back towards his stoop. Appointed official ball retriever, the tallest of the boys jogs over to the corner of the street, where the ball sits beguiling, in front of the bodega. Right as the boy moves to pick up the ball, a man in a blue uniform turns the tight corner and the two collide. The force is felt, though unevenly, by both. The boy stands up and looks up at the officer, who looks down in turn and, registering to threat, pats the top of the young boy’s head. He says something, probably platitudinal and nonchalant, oblivious to all tensions, likely throws in a “kiddo” or “bud” at the end, and keeps on his way. The boy, whose face has remained the same implacable mask, stands still and watches his acquaintance walk away. And then, with such deliberation that seems to have been rehearsed in front of mirror, the boy lifts his right arm in a fist to the man’s back, keeps it there hovering, with his middle finger ceremoniously raised.

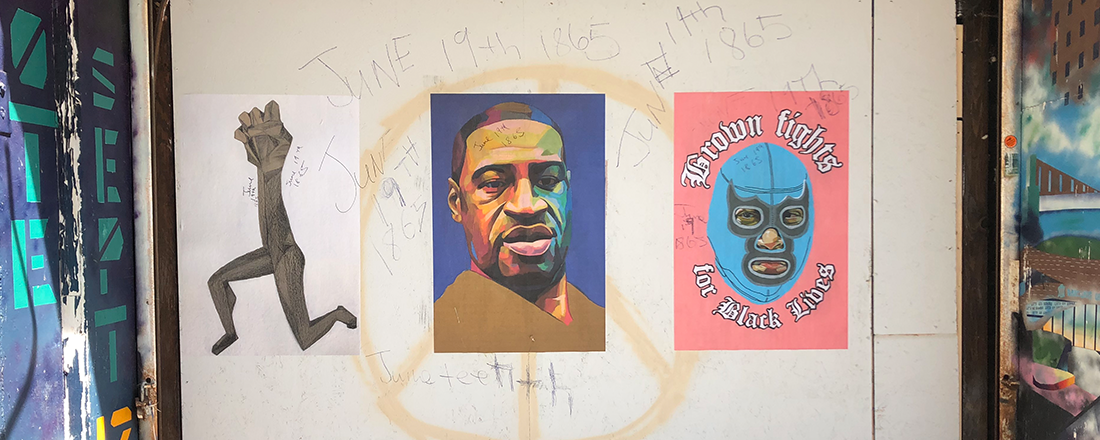

Note to the reader: I initially set out to write a piece about the months at the New York marches protesting the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade and the countless other victims of police violence. While trying to bring it all together, I found it incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to compose a neat and encompassing narrative. It might be a natural inclination to find resolution when writing, but until justice has been brought for Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, and now Jacob “Jake” Blake, this narrative has no end. When it became clear that this piece would not flow as I had envisioned, I instead set out to describe a series of recollections about specific people that struck me — some mentioned here: the couple, the two friends, and the little boy — who punctuated the vociferous moment. I cannot write a narrative that feels whole, resolved, and singular because that would feel disingenuous to the movement still happening and the hundreds of others doing the taxing work of disseminating information, posting educational resources, and mobilizing the masses: Nia White, Chelsea Miller, Nialah Edari (collectively @freedommarchnyc), Hennessy Garcia, Larry Malcolm Smith, NoName, @justiceforgeorgeflydnyc, the NDN Collective for Indigenous power and justice, Rachel Elizabeth Cargle, and everyone else whose names could fill this page.

Photos courtesy of the author.