JOE MADSEN, ALEXANDRA REALE, SWEDIAN LIE, NATALIE GALLAGHER, and NORA ROSENGARTEN

Joe

Fowler Street was dead. Like literally dead. Roxanne expected traffic to be light, but this was just creepy. Except for two cyclists up ahead, her U-Haul was the only thing moving on the downtown four-lane road.

“Babe,” she said into her phone. “I thought the move would be easy, but not this easy. I’m so weirded out right now. But anyway, I’ll be there in like 45 minutes. Call me when you get this. Love you!”

When she hung up, her phone buzzed with another insane pandemic update. Death counts. Unemployment rates. Trump White House response. Eyes glancing at the road, Roxanne texted the link to her boyfriend. Everything’s crazy, she wrote. And everything was. Including her. Just four weeks ago, Roxanne was near the end of her rope with Abel. Three months of dating hadn’t gotten any less boring. And when the quarantine struck, even sex was off the menu. He lived an hour away in the suburbs.

But every time she tried to end it, Abel would talk about where he lived. The big backyard. The deck. The grill. And the woods with trails stretching for miles. Plus he had a husky.

“Wish you were here,” he’d always say. “It’s so pretty. The only thing missing is you.”

Roxanne hated that, but she loved the mental image. And after one bad day in Whole Foods, squabbling with a gay-male couple over toilet paper, she had a sudden change of heart.

She called Abel. “How do you feel about me moving into your house?”

And the rest was speedy history. Two weeks later, in the middle of a pandemic, Roxanne broke her lease early, packed up all her things, and began her exodus to the suburbs 15 years sooner than planned. I’m actually really excited, she’d say on Zoom calls. To which no one would respond. A friend once texted her by mistake, clearly intended for someone else on the call: COVID broke Roxanne. She’s lost her damn mind.

“Fuck ‘em,” she muttered to herself, chugging along in her U-Haul. When she took a turn off Fowler, the phone started buzzing with a call. It was Abel.

“Hey, babe,” she answered.

“Hey, we have a problem. You should pull over.”

“What?” she said, veering toward the curb and parking. “Why? What’s wrong?”

“The house is being fumigated,” he said. “The whole place is infested with bed bugs. I have to get all my shit out.”

She stared at the wheel. “I’m sorry, what?”

“I have to leave my house today. You can’t move in here yet.”

“What— when did you find out?”

“This morning,” said Abel. “I had a feeling something was wrong a couple days ago, so I had an exterminator come by today to check it out. Says I gotta evacuate right now.”

Roxanne couldn’t believe this. “And you were just gonna let me move in with all my shit, knowing that you might have bed bugs? And where the hell am I gonna take all this stuff? I don’t have an apartment anymore.”

“Look, I know it’s not ideal,” he said. “But I’m moving in with my parents for now, and I already asked about you. They’re totally OK with you crashing. And they have plenty of space in their garage for your stuff.”

She was whiteknuckling the steering wheel.

“Roxanne?” he said. “Hello?”

“I’m here, Abel,” she said. “And I’m gonna say something I should’ve said a month ago. We’re done. This is done. Enjoy life with your folks. Shame I’ll never have the pleasure to meet them.”

“Hey, baby, wait—”

But she hung up and started scrolling through her contacts for a friend. Two things, she told herself feverishly. Just two things. A place to sleep and storage. That’s it. She found a name and hit dial, swallowing her pride.

The phone rang twice before someone picked up. “What’s up, sexy?”

Roxanne took a deep breath. “Remember when you said I’d lost my fucking mind?”

“Yeah,” said Rory. “Thought you were done talking to me after that.”

“Well,” said Roxanne. “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Alex

Rory put his phone down and smiled to himself. Sure, it had been a year since he’d seen her, and it had ended poorly, but in these times of COVID the rules of engagement were unrecognizable. And now he’d have a hookup buddy without breaking quarantine.

He cast an eye around his apartment. He’d have to tidy up a bit before Roxanne brought all her shit over. Unemployment had brought out in him some unfortunate tendencies. The remnants of a Trader Joe’s frozen pizza moldered on the coffee table, and the carpet was obscured by a layer of clothes. All his talk of “freedom to choose my own hours” and “not reporting to a boss” had been great for impressing a girl over drinks, but it turned out that “contract creatives” were first on the chopping block during a crisis. But he was handling it. He was sending out dozens of chirpy LinkedIn messages a day, ignoring the voice in his head (it sounded a lot like his dad’s) that said “computer science would have been a more practical major.” Yeah, but those drones didn’t care about politics or art or literature, right? All they did was code!

Roxanne. Right. With all her stuff. He grabbed his mask and walked out the door, going over in his head what he would need to buy at the grocery store to accommodate two people in his little apartment. He’d have to stock up on tequila. She had been adamant about each night out beginning with the ritual of lime wedges, salt on the crook between her thumb and forefinger, and the cheapest crap they could afford. He remembered only bits and pieces of that first night — her black crop top, the Lysol smell of that horrendous bar right off campus, the salty taste of her mouth. They didn’t really talk about what they were to each other after that. Their friend groups had convenient overlap and they had convenient sex. They were both good at compartmentalizing, so any feelings that threatened to surface were redistributed to writing (him) and sports (her). And after college when everyone was doing that thing where they join a kickball league or fall deeply in love with their consulting job, they drifted apart. The night they met to “catch up” had started out innocently enough, he thought, until it turned into an angry post-mortem of their not-relationship. Like an autopsy with no body. And now it had been a year, and she was going to be with him for the foreseeable future.

He entered the store, feeling the blast of cool air from the A/C and registering the weirdness of the scene: zombies in masks, nervously pushing carts and avoiding any aisle that wasn’t close to empty. Was this the new normal? He pulled some frozen chicken off the shelf and briefly wondered if he had been too rash in saying yes to Roxanne. No. All this time off from each other would prove to be healing. They could start over together as adults. There was no point in thinking ahead in the time of coronavirus. They could just see how it went, day to day.

He missed the time when grocery shopping was mundane. Now it set off alarm bells in his head about stalled income and hand sanitizer and the end of the world. Maybe he should actually take that coding class. Oh, forgot paper towels. He turned his cart around and saw a woman at the end of the aisle who looked familiar. Dr. Abernathy, his therapist, looking exhausted.

Swedian

She was staring at the last pack of paper towels on the shelf.

The last time Rory saw Dr. Abernathy was six months ago, when the end of the world was the name of an R.E.M song and not a lived reality. The sweet scent of striped carnations in her office and the soft supple texture of her couch were clearly designed to create a warm and welcoming environment for her patients — and for the most part, they worked — but they were never enough to keep the skeletons at bay. At least not in the decade or so that Rory has been seeing her.

She kept staring at the paper towels, her eyes continuously shifting up and down, up and down.

The last conversation Rory had with Dr. Abernathy — or “Dr. Abby,” as he sometimes called her — in that tan, coffee-colored office was about secrets. It was a story from years ago, when he was in college.The story started in a class called “Machine Empathy,” which was taught by Prof. Culliven, a robotics professor who was also a philosopher. On that sunny, lazy afternoon, Prof. Culliven began the class like he always does—with a question.

“Why empathy?”

The class is called “Machine Empathy,” for Christ’s sake, thought Rory. He was in this class because “Advanced Artificial Intelligence” filled up like bacteria on a petri dish — and because of her. That auburn hair. The deep, ivory eyes.

“Before we can begin talking about empathy in machines and robots, we need to talk about empathy in humankind first. Here’s a question: Do we need it?”

The slight dimple in her cheeks. The birthmark right inside her left ear. The coral-colored lips.

“Anyone care to answer the question?”

The maroon scar that cut through those lips.

“If we don’t have empathy, how are we any different from animalkind?”

Her voice shimmered in the sunlight.

“If we don’t have empathy, what’s stopping us from killing each other, like animals do to survive?”

“Very good, Ms. Abigail. That is the most common argument for empathy…”

The rest of the class and Rory’s memory of it drifted away, like the tide retreating, leaving behind bits and pieces in the sand — kernels of memories, mostly of her. Her presentation on cognitive empathy and its difference from emotional empathy. Her research on the evolutionary advantages of empathy, as well as the heated conversations that ensued. Her smile and the dimples that deepened because of it.

In the 16 or so weeks of “Machine Empathy,” Rory didn’t speak to Abigail once. Mostly because it was clear — to Rory, at least — that both of them belonged in vastly different social circles, but also because Rory knew he shouldn’t speak to her. Not yet. It needs to be the right time, Rory muttered under his breath. It needs to be the right time.

By the time that time came along, she was gone. As if the tide had swept her away.

“What was it you wanted to say to her,” asked Dr. Abernathy.

Rory stared out the window, into the drifting clouds. They were plentiful that day outside the coffee-colored office. There was no shimmering of the light.

“What I wanted to say was… I know why we need empathy. We need it so we can understand why we do the things we do. To each other. To ourselves.”

“I know why you did it.”

Rory stared at Dr. Abernathy, who was still staring at the last pack of paper towels on the shelf.

His phone rang, breaking the silence of the moment. Dr. Abernathy turned, and looked at Rory. Behind her was Abigail.

Natalie

As soon as they saw Abby, she booked it. She wasn’t trying to spend any more time with doctors.

She hadn’t told anyone, but she already had COVID-19. Did the whole shebang — hospital, ventilator, the works. It was terrifying. She thought she wouldn’t make it. But who would she tell?

Anyway, she got out of there ASAP, hoping they wouldn’t tell Zeph they saw her.

Abby left her, you see. Heartlessly, as lockdown began. She learned they would have to be together — really together, continuously, no breaks or space or personal time — for months. Zeph was kind of into it, but the idea made Abby panic in entirely new ways. She just couldn’t do it.

She couldn’t even handle it reasonably, talk it out, figure out something halfway. Who knows, maybe they could have salvaged something. Anything. Instead, Abby moved out the day before work-from-home started. Left a Post-It note like a true tool.

Two days later she went from the hotel to the hospital. While she was awake, she agonized — could she call Zeph? Z was her whole family, and Abby had walked out like it was nothing. Moron. Could she call anyone else, and would we have to talk about why Z wasn’t there? And then Abby was asleep on a ventilator making no more choices.

Walking away from the office, Abby shook her head, failing to clear her mind. And the goddamn mask was so itchy. And supplies so heavy. Was she late?

She hustled, opting for the smaller, less-crowded streets. Passing the shuttered parts of downtown, nostalgia pricked along her skin. She forgot how much she loved this city, the nooks and crannies and crassness and beauty. The coffee shops looked especially sad, somehow. Nobody lurking over anybody’s table spot, nobody with a second monitor, nobody who came to work but ended up scrolling Reddit.

Apartment hunting was brutal, as expected. Not that prices were so bad, but there was even more of a premium on porches, balconies, access to an alley. Postings for buildings without elevators went quickly. And Abby was terrible at this anyway — Zeph always pulled a magic trick and found a great place to live. Abby wondered if she’d been cleaning at all since Abby left. Had the place descended into Zeph’s natural slob habitat?

Abby saw a few for-rent signs and took quick pictures. Then remembered she was late. She left the side streets for the big street and made her way toward the crowd.

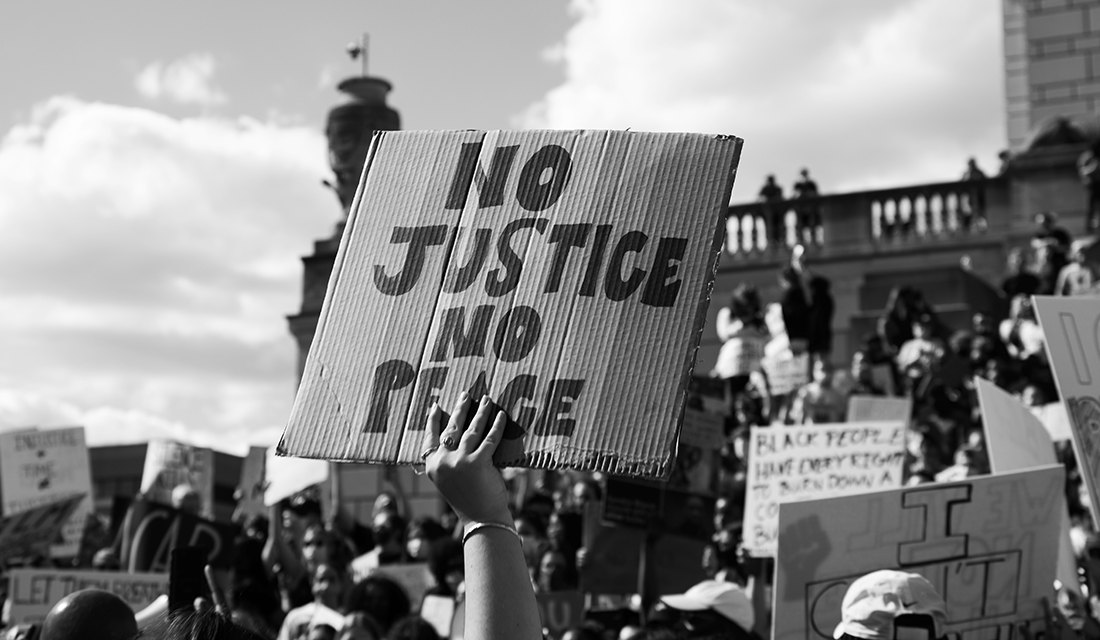

Joining the protest, Abby was surprised. Zeph was there. Six feet to her left, masked, marching, shouting. She met Abby’s gaze and her eyes did that crinkly smiling thing. Who knows?

Abby lifted up her sign, and added her voice:

NO JUSTICE

NO PEACE

Nora

Gingerly, she lifted the piece of roughly carved cardboard onto the narrow windowsill where it leaned at an angle. The top pressed against the cool metal of the screen, tenting it out toward the blue-gray sky where the sun was setting. After triple-checking that the sign’s message — “DEFUND THE POLICE” — was correctly oriented, she stepped away from the kitchen window. And exhaled.

She’d spent the last three and a half hours at a protest sponsored by the local NAACP chapter. About one hundred and fifty people, maybe two hundred. They’d gathered in a parking lot, then marched around town carrying signs and chanting. Periodically, speakers delivered speeches on racial justice, police violence, and Black liberation. The sun beat down relentlessly, and at various stops the protestors were met with bottles of water bathing in tubs of ice. Heat rose up in waves from the baking asphalt paving the residential streets outside of the town’s center, while sweat streamed down faces, arms, and calves, accumulating and then soaking the edges of cotton face masks.

Paused at a street corner, she smelled the mixture of freshly mowed grass with exhaust from a beat-up bright red pickup truck that raced past. Her heart felt timid, shaky, and her voice often failed to project as it once might have unhindered by protective gear. She felt out of sync, after months of isolation, overwhelmed and exhausted by a socially distanced gathering with five friends, let alone a protest. There was nowhere else she’d be, of course — when the NAACP protest came up on her Instagram that morning, she had no doubts about attending. But now that she was here, she’d been made acutely aware of how thoroughly the past fourteen weeks had eroded her sense of her own capacity. Like an atrophied muscle, her mind and body felt sore from walking, thinking, moving; every decision was sluggish, impeded by fears, anxieties, and the rustiness of underuse.

She tried to maintain six feet of distance, but there were times when this was difficult, and even impossible. Two thirds of the way through their march, they’d received threats — the red pickup truck’s driver had yelled his intention to drive his car into the gathering — and so they reorganized their formation, placing children and babies safely on the sidewalk while adults walked in the street, flanking the parade of strollers, light-up sneakers, and impossibly small (and unbelievably adorable) bikes and trikes. She’d barely registered the threat of violence — not because it was insubstantial, or because she doubted this person’s intent — but because for a long time it had felt like violence was always already happening. She felt a rawness beneath her sternum, which, coupled with the tingling in her spine and shooting, flaring heat along her forearms and shins, had been her constant companion in the past months. She’d described it as her nervous system “turning on” like a creaky old boiler in a rundown house. Something roaring to life with worn ferocity.

“Black lives matter!”

“Black lives matter!”

These calls — their calls, her calls — echoed off of the surrounding mountains, which loomed in the distance like the benevolent, verdant creatures they were. She felt held by those mountains, much as she felt held by the crowd surrounding her. Like a puppet lifted by strings her legs moved one after another, her mouth opened and closed, and she managed to continue existing. The crowd chanted on. It was a sensory overload: the smells and sounds and sight of so many people, moving and walking and crying and drinking and singing and chatting and chanting and eating and smiling in beautiful cacophony.

Back at home, the apartment felt like an ill-fitting garment, as if all the moments of expansion and contraction had left the neckline too loose and droopy, sleeves cutting into biceps, hemlines alternately bulging and curling in on themselves. Her eyes traveled the familiar walls and grayish carpet, ears echoing with the chants.

Her reverie was interrupted by the soft chiming of her phone. Her work phone. She shook her head slightly, as though waking. Then she pulled the phone out, and answered.

“Dr. Abernathy speaking.”

It was a patient in need of guidance. As though she was floating on the ceiling, Dr. Abernathy watched herself expertly de-escalate her patient, and consider their care going forward. She watched herself going through the steps and deftly identifying her patient’s needs. If this was all life was, she found herself musing, “I’d be so good at it…”

The phone call completed, she sat down on the couch in her living room. The quiet apartment settled around her into an aching stillness. There was so much to do: strip, then shower; laundry; reschedule a socially distanced visit she’d planned to her mother’s; reset her quarantine for two weeks, etc. Her phone rang, again. Personal phone this time, a chirpy, upbeat ding-ding-ding that echoed. She answered.

“Hi, Aunt Delilah? Are you there?”

“Yes, it’s me. Roxanne, is that you? Are you okay?”

“Um, I’m okay, I guess, but I need your help.” There was a long pause. Dr. Abernathy could hear traffic in the background, someone yelling.

“I need your help,” this time the voice was stronger, more self-possessed. “I need somewhere to stay. Everything got really messed up and, well, Abel and I broke up and then I was maybe going to stay with some other dipshit guy I know…” Roxanne went on, but Dr. Abernathy was only half listening. Her mind was awash with pros and cons — could she ethically welcome her niece into her home when she had not yet quarantined for the requisite two weeks? Moreover, could she ethically say no?

“Rox, I uh, I—” she started, then stopped. “Rox, I was at a protest today. I wore a mask, and kept six feet apart where I could, but I want to be honest with you. I understand if this changes things. I’d love to have you here, honestly, but I also don’t want you to be in danger.”

The static silence felt deafening. Roxanne, or someone near her, coughed loudly.

“Okay. Yeah. I mean, I guess fuck it. I need somewhere to stay, I can’t keep driving around with all my stuff forever. Yeah. I trust you, Aunt D. Be there in 15?”

“See you in 15.”

Dr. Abernathy sat on the couch, trembling. She hoped she’d done the right thing.