DELESSLIN GEORGE-WARREN

“When asked by an anthropologist what the Indians called America before the white men came, an Indian said simply, ‘Ours.’”

– Vine Deloria, Jr.

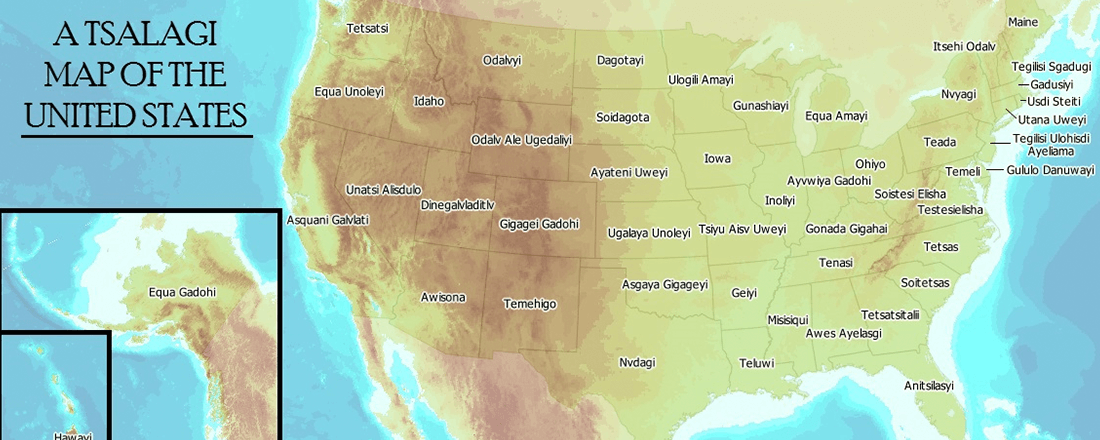

How many productions have you watched on indigenous land? Your first estimate will probably be low: maybe you saw Unto These Hills near the Harrah’s Cherokee Casino in NC? Maybe you visited a reservation out West and found yourself watching a 1.5 hour long re-enactment of tribal history? Although those productions advertised to be on indigenous land are few, every production in the United States of America is on indigenous land.

A Cherokee (Tsalagi) Map of the United States | Source: Decolonial Atlas

Where are Indigenous Lands?

The United States loves founding myths. George Washington and the cherry tree. Revolutionary freedom fighters dumping tea into Boston Harbor. The idea that the United States was founded on freedom and pursuit of happiness for all humans. However, no myth is so ingrained in the imagination of the United States as the idea that explorers, settlers, and pilgrims discovered a land mostly untouched by human hands. For example, in a recent love letter to Andrew Jackson, former Virginian Senator Jim Webb asserted that President Jackson had “found wealth in the wilds of Tennessee.” I think the Cherokee, who had lived in the land he is referring to as “wild” for millennia before Andrew Jackson was born, would disagree with the characterization of their lands, peoples, and societies as “wild.” This mischaracterization of colonized land is common.

Catawba Indians | Source: Wikimedia Commons

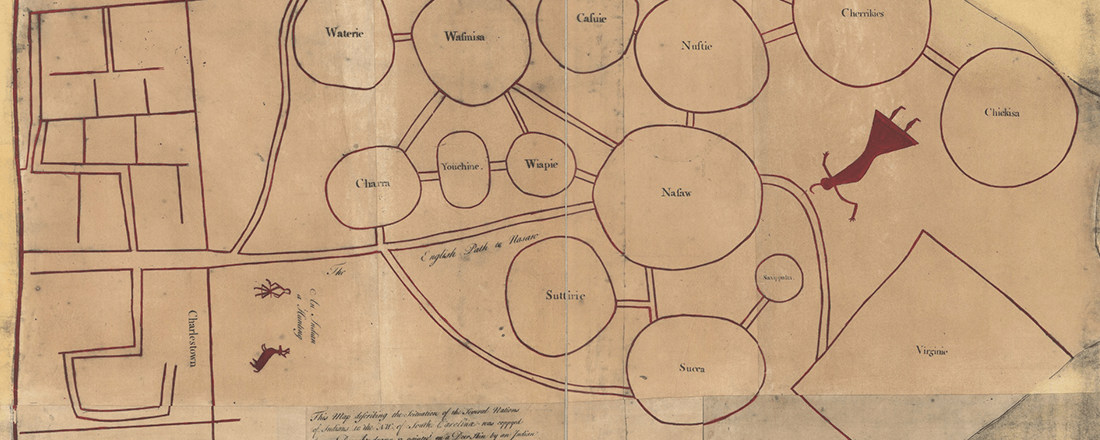

As a member of the Catawba Indian Nation growing up in South Carolina, maps were used in my classes which fabricated a history where my tribe did not exist. The Catawba have lived along the Catawba River since at least the end of the Roman Empire. In fact, we held most of what is now the central and western part of the state until the late 1760s when we negotiated a series of treaties where we agreed to limit our activities to a smaller area (i.e. a reservation). However this reservation was still 200,000 square acres, until South Carolina illegally took the remainder of our land in the early 1800s. A simple Google search for “13 colonies” uncovers an almost universal acquiescence to depicting South Carolina in its modern shape, despite the historical reality being drastically different.

1721 Catawba Map of South Carolina | Source: Wikimedia Commons

The lands on which the United States of America is built weren’t just populated and overseen by multiple indigenous nations in a general sense.

The sites that were targeted for the creation of new settlements were chosen specifically because indigenous societies had already made them hospitable to human life.

In 1611, the same year that Shakespeare’s The Tempest was premiered, English colonists expanded in North America for the first time. The fort at Jamestown — it is a common piece of historical revision to refer to ‘Jamestown’ as a town, colony, or settlement when at its inception it was understood as a fort, a specifically economic and military venture — realized that their position was decidedly untenable as a permanent settlement.

To rectify this situation and ensure a return on their economic backers’ investments, the leaders of the Fort of Jamestown decided to expand further inland to an island referred to by the colonists as Henricus. Henricus wasn’t chosen because it provided the optimal raw resources for the British colonial experiment, but because it provided ample resources, strategic location, and an already established infrastructure.

Colonial Map of New York, then called New Amsterdam | Source: Free Amsterdam

Claiming indigenous infrastructure — the intricate continental system of trails, clearings for farming, waterways and irrigation systems — was used consistently in English colonialism. Broadway, the street which has become synonymous with New York theatre, is another example. The road, which is now used ubiquitously as a symbol of the metropolis, culture, and civilization, is built on the Wickquasgeck Trail which was used by the Algonquian before any colonial powers ever arrived on Mannahata.

To legitimize the land taken from indigenous people, not only must Indians be erased from the spaces now occupied by non-indigenous people, we must also be erased or minimized in the retelling of important historical dates.

Possible portrait of Crispus Attucks | Source: Wikimedia Commons

For example, Crispus Attucks, widely considered to be the first casualty of the Revolutionary war, is often depicted as white, but was of African and Wampanoag descent. Hamilton, the widely successful ‘hip-hopera,’ leaves Indians mostly unmentioned throughout. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s vision of early American politics is a world where Indians are peripheral despite the fact that the historical Alexander Hamilton and the other revolutionaries were constantly interacting with indigenous nations. U.S. history is indigenous history. It’s just not a story U.S. theaters, writers, actors, and storytellers like to share because the U.S. frequently turns out to be the villain — an overly-aggressive, imperial, foreign power.

The Missing Context

Research has become the contemporary theatre artist’s best friend. I have yet to be in a production that has not integrated research into the production schedule. I am a young theatre artist so I’m not sure if this is a new trend or an old one — in all likelihood it is both new and old — but the research instinct is also an instinct towards context.

The contemporary artist wants to know the geographic, political, and historic coordinates of a work’s setting. The artist researcher wants to how a how a work fits into the context of the block, the neighborhood, the city, the state, and the nation in which it is premiering.

However as subjective beings undertaking the overly-wrought, objectivism-soaked ceremony of ritual, we begin this process with assumptions.

Assumptions, as syntheses of experiences and consumed media, aren’t inherently bad. However assumptions more often than not flow along the well-worn platitudes of those in power. Our assumptions about the space of the United States are grounded in the stories we’ve heard and continue to tell one another.

Case Study: Cherokee by Lisa D’Amour

Two couples — one black, one white — flee their suburban pressures and try to connect with nature by camping in a forest near Cherokee, North Carolina. But their vacation is upended when one member of the group vanishes and the others are visited by a mysterious local…who brings the otherworldly woods to life and unearths buried desires that might change their lives forever.

– Synopsis of Cherokee

In early 2014 Wilma Theater in Philadelphia premiered Cherokee, a new work by Lisa D’Amour. The work was later staged at Woolly Mammoth Theater in Washington, D.C. If we ignore the New Age tropes — one character asks her amnesiac husband, “Do you think it triggered some kind of primal knowledge or something?” — we can see this piece as full of radical possibilities of individual and societal transformation. And because racial diversity is explicitly mandated by the work, it could also be read as a proposition for a racially integrated future.

Cherokee | Source: © Woolly Mammoth Theater

But the fantasy of people coming together on neutral territory — rented from Indians at a discounted rate — only happens in a world without history. Mike, the character of miraculous transformation, says of his change, “A person. Manifesting personness. Without the burden of history.”

Lenni Lanape, also known as Delaware Indians | Source: Penn Treaty Museum

In Lisa D’Amour’s work, the campers (i.e. settlers and ‘arrivants’) claim the campsite as the stage on which they reinvent themselves and their relationships but Cherokee takes for granted the land upon which it is produced. The work was originally premiered at Wilma Theater in Philadelphia. Of course this land was not always Philadelphia — it was known to the Lenape nations for millennia before Columbus terrorized the ocean blue.

The assumption that we are starting with a neutral space and constructing meaning on top of it is a consequence of America’s first operational foreign policy: Manifest Destiny. Once the U.S. succeeded in taking controlling through brute force all of the people and land between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, it became important to constantly validate the occupation of indigenous lands. That the United States has some kind of legitimate claim over land it aggressively colonized is reiterated until it becomes common sense — something always communicated but rarely stated and never questioned.

Understanding Cherokee as a work performed on occupied indigenous land begs the question — who wins when we forget history? This issue is brought into particular relief because of the title and topic of the work but are we not all at fault for reasserting settler rights when we perform on land stolen from indigenous people without actually addressing that context? Silence in situations of oppression is quiet acquiescence, not neutrality, so not mentioning the continued occupation of indigenous lands reasserts the United States’ colonial presumption of control from sea to shining sea.

Doing Better

Reiterating tired and inaccurate stories about the history of the United States is simply bad storytelling.

Theatre has a complicated relationship with “reality.” At times, it purports to know truth about the nature of the world. At other times theatrical works assert their rupture from reality. In fact, “suspension of disbelief” — that ubiquitous theatre term — is about how the audience receives theatre and understands it relative to their idea of reality.

Conversely we can say that theatre is about suspending reality to create something else on top of that clearing. But this suspension of reality is never a complete break; we want our theatre works to have some relationship to reality so we selectively suspend reality. For example, most theatrical productions don’t ask their audiences to suspend their belief in gravity, or the United States as a legitimate structure, or strict gender binaries to enjoy a theatrical production.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

However, indigenous people are always asked to suspend their disbelief about shows which reassert that the United States came into its current shape organically instead of through the systematic dispossession of land from indigenous people. For example, Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson suspends our disbelief that anyone during the 1800s used Green Day-esque rock-opera ballads to communicate with one another. However, it selectively retains reality by dramatizing certain aspects of his life: Andrew Jackson did become president; he did preside over the expulsion of Natives from the eastern United States; he did advocate for universal white, male suffrage. However, in the imagined world of Alex Friedman and Alex Timbers native dispossession and genocide is understood not as central to Jackson’s life and works but as a peripheral moment. Reiterating tired and inaccurate stories about the history of the United States is simply bad storytelling.

Theatre is a frame, of course, outlined by the space, the audience, and the performance. Theatrical work, like all frames, must exclude many things in order to focus on a person, place, event, or idea. It would be facile to respond to this call by saying that indigenous issues are simply outside of the frame of a work. The horrific Indian removals that tore land from Indian nations and placed it into the hands of settlers like the Ingalls were simply outside of the scope of Little House on the Prairie. Placing indigenous voices outside of the frame is the historically safe choice in American theatre.

So how can non-indigenous artists make better work? Hiring more natives to write, act, produce, direct, and dramaturg in staged works and paying them for their labor is a good beginning. If this poses problems for your production, then you can always start by momentarily suspending your belief about the lands on which you are performing. A few questions to start that process:

- Where will this work premier? Where is the work set?

- Whose land was it in 1491?

- How did it come under control of non-indigenous people?

These questions aren’t intended as ‘indigenous inclusion’ checkboxes but as starter tools for disrupting our assumptions and setting us on a path for a more truthful theatre.

“I will tell you something about stories … they aren’t just entertainment. Don’t be fooled. They are all we have, you see, all we have to fight off illness and death.”

– Leslie Marmon Silko