CELESTE CHEN

He likes to watch her eat cake. This is what they do after fights. He will stop by Pete’s, the tight corner bakery up the road, and bring home whatever feels right. Some nights he buys a slice of their chocolate ganache, and on other nights, when he wants a slice too, he takes a stab at the carrot cake. She has never criticized his choices, but he knows that he doesn’t always get it right: she’s not the biggest fan of carrots, or of carrot cake. Once, after one of their more spectacular and thunderous fights, he bought two entire cakes — angel food and a coffee-walnut. He wanted to get it right that time.

Tonight, he brings back a slice of plain vanilla cake. It’s November, and pies and cheesecakes have supplanted cakes on the menu. The loud couple in front of him picked out the last few slices of the blueberry cake, complete with buttercream frosting, for their equally loud children, and so by the time it was his turn, he was left with either vanilla or carrot. The choice was clear.

When he returns, she has lit the candle in the kitchen. On the table, a small plate, the size of a child’s head, is framed by a single fork and a glass of milk. He sets down the small cardboard box; Pete himself had tied it up with a pink ribbon and a little flourish. (Make her smile, son, hmm?) Now, she cranes her head forward. Her wrists, slender-tender, scissor through the cardboard like twin silverfish as she unwraps the box and carefully transfers the slice onto the plate.

“How was Pete?” she asks.

“Good. He was about to close up. This was one of the last slices.”

“Would you like any?” She waves the fork in his general direction.

“No, I’m not really hungry.”

She makes a face, huffs a bit.

“Suit yourself.”

He takes the chair across from her and studies her. With her hair so short and arms askew, she looks almost alien in her lemon slip dress. There is something sweet, but not quite fully there, about her. He has known this for a while now. It used to bother him, a stubborn thought-worm that he couldn’t shake off: What did she actually think? Did she actually understand him? Understand them? And the one that used to rattle him the most: Was this all just an unconscious, well-intentioned ruse? Was she really only interested in what he had to say, not because it was intrinsically interesting, but rather because she loved him? What was she hiding?

“This is really good,” she says, “thank you.”

He isn’t sure quite how to respond, and so he continues to watch her from across the table as she twirls her fork through her slice.

“I’m sorry,” she says. She chews slowly; he can hear her swallow. He imagines the cartilage tensing and collapsing underneath skin. Esophageal peristalsis.

“I’m sorry too,” he says.

Judith Beheading Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi | Source: Wikimedia Commons

He doesn’t really know what to do when she cries. If she believed in something greater than herself, she would have resorted to prayer by now. She likes the stories — poor Agnes, who lost her head; Joan of Arc, all the Teresas. When she learned of religious ecstasy in elementary school, it felt so real and consuming. There was something romantic about the agony. All the little statues of women with their lips halfway parted, their hands clasped tightly, their eyes skywards — they had always looked to be in a state of perpetual orgasm.

Two years ago, he took her to Italy for their three-year anniversary. They spent a few days in Naples. On their last afternoon, they wandered through the Palace of Capodimonte, where she stumbled across Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes. Standing in front of it, she felt something unlodge as she stared into Holofernes’ still-open eyes. A ribbon of disgust uncoiled in her belly; she didn’t like this — whatever this was — but she didn’t dislike it either. Her body responded by heaving her shoulders and choking her up.

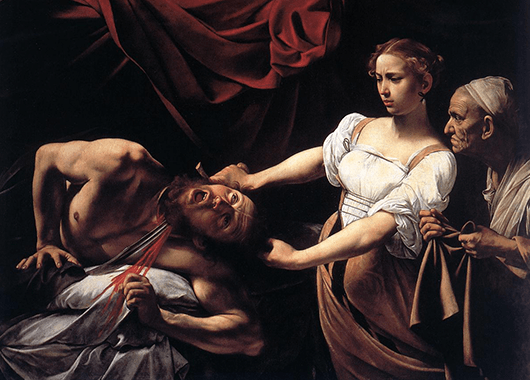

Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio | Source: Wikimedia Commons

He was dumb and mute beside her as she cried, but she was grateful that he had enough sense to keep silent. After Naples, they ventured to Rome and Florence, where she kept finding herself confronted with this vision of Judith as she cleaved Holofernes’ head from its body. There was Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes at the Palazzo Barberini, where Judith, resplendent with an expression of intense focus, had already driven her sword through Holofernes’ throat. And then a few days later, there stood, in the Palazzo Vecchio, Donatello’s tribute to the coup de grâce.

It’s been a while since she last believed in the parades of ecstasy and devotion, but that has just meant that she has had more time to create her own icons. She will spend afternoons watching movies like The Notebook, Waiting to Exhale, and Lust, Caution, and then locking herself in the bathroom to rest her hot face against the clammy tiles. And then she’ll watch them again. Sometimes she will allow herself to hope that maybe understanding the way they feel and the way they act will shed light on her own questions.

Tony Leung Chiu-Wai as Mr. Yee and Tang Wei as Wong Chia Chi in Ang Lee’s 2007 film Lust, Caution | Source: © Alphacoders.com

Instead, she has found that, when she cries, she also cries for Rachel McAdams in The Notebook, for Bernie in Waiting to Exhale, and for Chia Chi in Lust, Caution. Their stories goad her on; when she cries, she is no longer upset with just the small tragedies of her own story. They tell her, No. No. Yes. Should she stay? No. Should she go? No. Why is she unhappy? Yes. She wants to tell him that she carries their stories and that they don’t need to be so upset. But still, they whisper, their perfect nails digging crescents into her thoughts.

She also wants to say, “This cake is communion.” She wants to find words to explain to him that this marriage consists of more than just two bodies in a certain mental orbit. That after every time they fight, the cake that she eats inevitably recalls its previous siblings: the strawberry cake he sweetly presented to her when she had been fed up with his drinking (he still never stopped); the red velvet slice after he took on two shifts on her birthday night; the double chocolate when he found her curled up crying after their very first fight. They have a slice of their wedding cake in the freezer, carefully wrapped in cellophane. A morbid part of her wonders if they will ever reach that point. She thinks she would serve it to him, if it came to that.

She eats her cake. Phone buzzes with an alert. Reads a story about a man who has bitten off a girl’s nose on their first date. Four and twenty blackbirds, picked off her nose.

He thinks of her most acutely whenever he’s high or drunk. When he’s drunk, he wants to jump off their ledge. It’s not a high apartment building, so he’d likely break a leg. Worst case scenario would be a shattered hip. It’s his femoral artery that would be at most risk. He knows it would never come to that, but it’s still nice to know.

When he’s high, though, he thinks about how insane this all is. In nature, things repeat themselves and then multiply: the branches of the trees, the branching of his neurons, the networked web (redundant, he knows). Leonardo da Vinci used to draw from nature when trying to nail down flight; Ramón y Cajal’s sketches of brain tissue all looked like roots and veins.

But her and him? They orbit each other, in concentric circles like some John Donne shit (though to be fair, he will always defend A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning; what a masterpiece). They will fight and he will buy her cake and they will make up, and round they go at each other until the next time. There’s no multiplication; only repetition. “Baby, baby, please, don’t go,” she’ll say, and he won’t go. He can’t. Was she so naive that she was staying because she didn’t know anything else?

Perhaps she will sleep with him tonight. He can see the sliver of her thigh beneath the table. He finds himself wanting it more than he’d like — he’s starving. She is halfway done with her slice, and she catches him staring.

He moves forward. Her breathing is ragged as he brushes the back of his hand against her leg. He thinks, if she were a bit smarter, she would aspire towards achieving the air of someone halfway between Michelle Pfeiffer in Scarface and Nabokov’s Lolita. But she’s not.

“Thank you,” she says.

“Baby, please—”

Everything is still as he stands up and she squirms back into her chair. It’s the chair that her father once sat in when he was young. It’s not quite a family heirloom, but it is the same chair that she sat in when she was seven, the same chair that her mother slumped in when her brother died, the same chair she used to excitedly wait in for him to come home. He watches her swallow that last bite of cake and it’s as if she is swallowing wholesale whatever it is that once made her young and lovely and whatever je ne sais quoi that once made her distinct.

He catches her practicing her smile sometimes and it makes him want to punch a wall. Nowadays, he just puts a slice of cake in front of her. She’ll eat it for them. The birthdays, the funerals, the fights — none of it really matters as long as there is cake. He can make her eat. He can make her happy. In his small existence, he can be a god.