SWEDIAN LIE

We live in a much more peaceful time than ever before. That might seem hard to believe given our current global political climate (rising extremist groups; cyber threats to international security; heads of state bragging to other heads of state about highly classified information; you name it), but in terms of mortal confrontations and conflicts, we are at an all time low.

This is not to say that the desire nor predilection for confrontation and conflict is not there (just look at who’s sitting in the Oval Office right now) but over the millennia, humankind have slowly — and, to be fair, with many false steps — moved towards a less fatalistic approach of resolving potentially violent disputes. Part of this is not only because of an emerging global diplomacy (as states began to realize they no longer live living in siloed civilizations) but also a general existential move away from the military arena to the sporting arena, which itself is a stage steeped with military connotations.

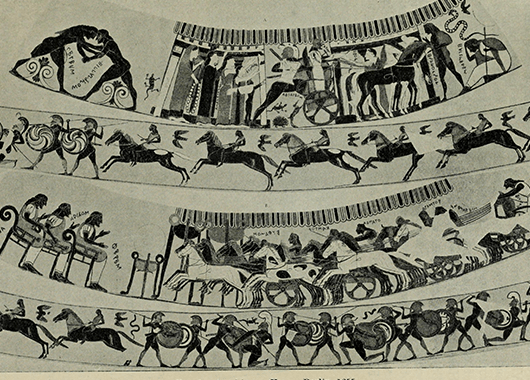

Funeral Games | Source: © Internet Archive Book Images/Flickr

For much of history, the term “sports” is synonymous with “training” — that is, military training. People, almost always men, competed with one another in a controlled environment in order to hone the skills and perfect the abilities required to survive and win a battle. In ancient civilizations such as the Greeks, Sumerians, and even the Irish, those who perished in battle were honored with funeral games, which not only commemorated them but also placed a positive spin to the brutal conditions that brought about their demise. Sports became a way to understand and perform the testosterone-drenched tensions and drama of a mortal confrontation, minus the mortal part. It became a liminal space whereby individuals can enter with their hearts in their hands, ready to give it up for a victory, but actually still return with it, ready to give it up for real in an actual military battle. The Ancient Olympics was very explicit about this performative element of sports, coupling athletic performances with ritual sacrifices as if to say that the only difference between sports and war is, indeed, whether you came back with your heart or not.

These days, sports are rarely as bloody as that during ancient Olympia. No longer is being an athlete synonymous with being a warrior, at least in the literal sense. That said, there is one particular slice of the sporting universe that still, at times, feel like war — and it’s no less bloody either. I’m talking about football derbies (the world game, not the one with million-dollar 30-second ad spots).

Steven Gerrard of Liverpool FC and Joseph Yobo of Everton FC clashing during the Merseyside derby | Source: © Football Off the Pitch

For those unfamiliar with the term, a “derby” in the footballing sense is a match between two local, usually rival, teams of a geographical location, which can be anything as small as a village town to a multi-city region. Probably the first ever football derby — and likely the one that gave the occasion its name — is an annual match between a team from St. Peter’s Parish and a team from All Saints in the English town of Derby. Given that it was a time before formalized association football, the game was chaotic and violent, to say the least, involving “up to a thousand players” and, in one instance in 1796, resulting in the drowning of a player. Since then, with the growing international popularity of football as an organized sport, the passion of those ‘thousand players’ have extended to the countless number of fans that support either side of a rivalry. As such, the aforementioned desire and predilection for confrontation and conflict grew beyond the athletes — it became a shared identity for the fans that bonded some and alienated others within the liminal space of the stadium. This identity defines your role as a warrior of one footballing side, even though you yourself are not participating in the actual event. This identity is a reminder that you still have an integral part to play in protecting and defending this partisan space. Without an athletic outlet to assuage the intensity of the rivalry or to perform the figurative duties of a warrior (to stand up for your community), the soldier instinct spills over into real-life bloody battles both on the field and in the stands. On derby day, football is no longer entertainment — it is war.

Let’s look at three football derbies that have become iconic internationally not only because memorable matches but also because of the unique socio-political conditions that underpin the rivalry: the Old Firm Derby, El Clásico, and the Merseyside Derby.

Up to Our Knees in F’in Blood: The Old Firm Derby

Like a pair of marble statues standing guard over the long and tumultuous history of Scottish football, the centuries-old clash between Celtic FC and Rangers FC — both based in Glasgow, Scotland — is one of the most anticipated matches in the Scottish Premiership calendar. The deceptively unremarkable name for this derby belies its incredibly violent, historically racist, and turbulent context.

Interestingly enough, the derby was given its unique name because newspapers of the time thought that the match — which today is estimated to generate about 120 million pounds for the Scottish economy — was mainly a money-making event between both clubs (ergo, ‘firms’) rather than a genuine intense local rivalry. You wouldn’t have guessed that from talking to fans of either clubs, though.

Source: © Daily Mail

The Old Firm derby became — as one banned song’s lyric say, “up to our knees in fucking blood” — so infamously tempestuous because of the complicated religious and socio-political context of its rivalry. Celtic FC was originally founded in 1887 in the poorer working-class Irish Catholic neighborhoods of Glasgow’s East End. The club crest features a bright green four-leaf clover that, although technically is not a shamrock, is still associated with Irish identity. Rangers FC was originally founded 16 years earlier, in 1872 in Glasgow’s West End, as a decidedly Scottish Protestant club. The club crest features the rampant lion iconography, which represents Scottish royalty. Tensions between Irish-Scots and native and Ulster-Scots were already present before either club came to be, mainly because of religious differences, but they were further escalated by the events around World War I. Irish-Scots — many of whom were Celtic fans — supported the 1916 Easter Rising, an insurrection against the British forces (which included Scots) that led to the founding of the independent Republic of Ireland, while native and Ulster-Scots — many of whom were Rangers fans — were traumatized by the tragedy on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, which occurred just a few months after Easter Rising and was the bloodiest day for the British in WWI, resulting in more than 5,000 casualties. As such, following 1916 many native and Ulster-Scots began to distinguish themselves as “loyalists” in opposition to the Irish “nationalists.” This division within Scotland seeped into football, with the emerging rivalry between Celtic and Rangers further reinforcing the sectarian borders that divided Glasgow and Scotland as a whole.

Crowd during the Old Firm Derby | Source: © FIFA

The deepest and seediest manifestations of racism and sectarianism emerged during the Old Firm derby, with incredibly offensive songs and chants that mocked historical tragedies suffered by both sides. Now-banned examples include the “Famine Song” sung by Rangers supporters, which ‘celebrated’ the 1840s famine that decimated the Irish population, and the “Ibrox Disaster Song” sung by Celtic supporters, which ‘celebrated’ the death of 66 Rangers fans during a safety barrier collapse in their home stadium of Ibrox. This division turned tragic in 1995 when Celtic fan Mark Scott was murdered following a football match — not even the Old Firm derby, but a regular Scottish football match — because he was a Celtic supporter who walked past a “Loyalist pub.”

There is one particular slice of the sporting universe that still, at times, feel like war — and it’s no less bloody either.

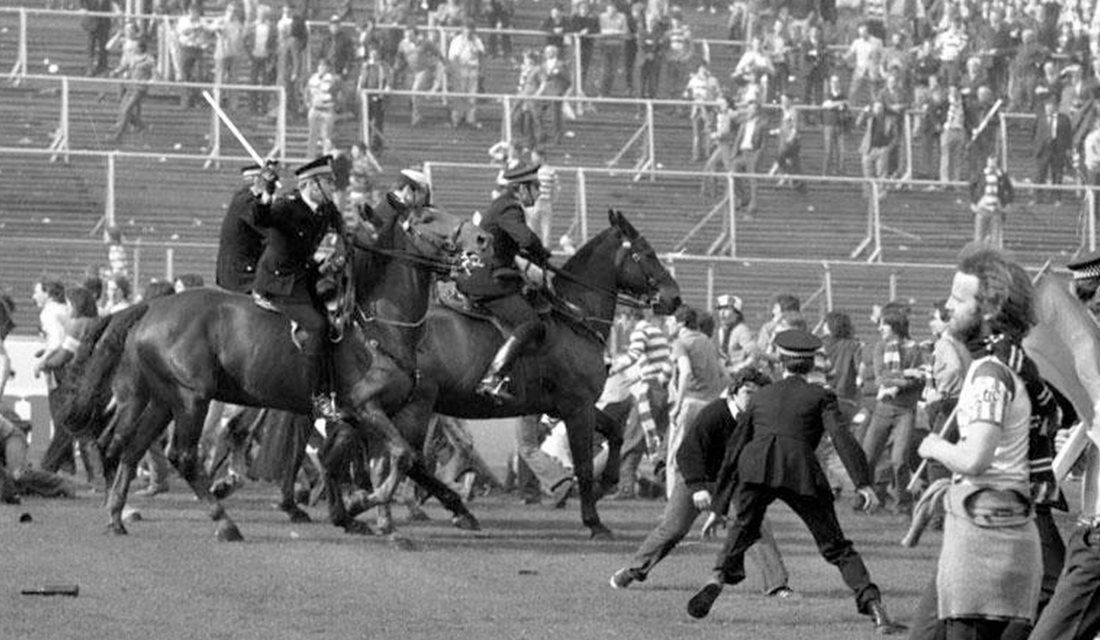

The infamous 1980 Old Firm derby, better known as the Hampden Riot, where drunken fans invaded the pitch and mounted police forces were deployed | Source: © Football Violence

Most people in Glasgow would argue that this sectarianism has dissipated over the years and that more and more supporters of either clubs no longer identified with the traditional religious and political stances of said club. Yet as recently as 2012, then-Celtic manager Neil Lennon, an Irishman, received homemade parcel bombs from Rangers supporters — luckily the bombs were crudely made and did not detonate. Bigotry dies hard, but it dies even harder when it is coupled with actual violence performed outside the liminal space of the sporting stage. In the case of the Old Firm derby, the dramatic historical context continues to color the occasion with a militancy that is breathtaking in more ways than one.

Club or Country: El Clásico

Technically speaking, El Clásico or “the Classic” is not a derby in the traditional sense, because the two sides involved — FC Barcelona and Real Madrid — are not from the same geographical region. FC Barcelona is from the Catalan city of Barcelona, which is more than 600km away from the Spanish capital of Madrid, where Real Madrid is based. A true Barcelona derby would be between FC Barcelona and Espanyol, while a true Madrid derby would be between Real Madrid and Atletico Madrid. El Clásico, however, has managed to capture the imagination of not only Spanish football fans but fans all over the world because of the incredibly political — and, at times, philosophical — context of their rivalry.

Source: © SigmaLive

FC Barcelona was founded in 1899 by a group of foreign and local footballers in Catalonia, a region that since the Middle Ages has, by one way or the other, been fought over by the French and the Spanish. When the club was founded, Catalonia was experiencing a surge of nationalism and the club’s founder, Swiss footballer Hans “Joan” Gamper, wanted to celebrate Catalonia and create a football club that embodies diversity and democracy, both values important to Catalan identity. Just a few years later in 1902, Madrid FC was founded. Being in the capital, the club was always close to the ruling power, which at the time of its founding was a monarchy. It is because of this connection that in 1920 they were renamed as Real Madrid — “real” means “royal” in Spanish — by the then-king King Alfonso XIII. Thus, from the very first beginning of their inception, both clubs are deeply rooted in and divided by opposing national identities and values. This national rivalry became even more intense during Franco’s reign in the 1930s. Even though presidents of both clubs suffered under the hands of Francisco Franco, FC Barcelona became the symbol of leftist resistance against the fascist Franco regime, which was based out of Madrid. It was during these times that FC Barcelona’s slogan, “mes que un club” or “more than a club,” emerged.

Sports became a way to understand and perform the testosterone-drenched tensions and drama of a mortal confrontation, minus the mortal part.

Gerard Piqué and Sergio Ramos | Source: © Associated Press/Daily Mail

In more recent times, the politics of Catalonia versus España has transferred from the national government to the national team. From 2008 to 2014 — what many consider to be the golden years of the Spanish national football team because they won three major international tournaments in a row: Euro 2008, the 2010 World Cup, and Euro 2012 — almost the entire starting eleven were comprised of either FC Barcelona or Real Madrid players. While this meant that they had probably one of the best teams in football history, it wasn’t without its fair share of drama. There were both Catalan players and Spanish players in the squad, which caused a lot of friction in the dressing room. Gerard Piqué, a Catalan native and a central defender for FC Barcelona, is well known for his outspoken support of Catalonia’s independence, including that of a proposed referendum. Sergio Ramos, a central defender for Real Madrid, has frequently criticized Piqué’s comments as disrupting the national team’s harmony. Given the amount of animosity between the two players, it is a wonder how they played alongside each other as the primary central defender pair during Spain’s golden years. It is clear that when it comes to El Clásico, at least for Piqué and Ramos, border politics has become personal politics — football players have become soldiers as well.

Crossing the Park Together: the Merseyside Derby

Both the Old Firm derby and El Clásico have shown a football derby’s ugly side, but there is one equally heated derby that’s known not for its chaos, but rather for its camaraderie. Dubbed the “friendly” derby, the Merseyside derby between Liverpool FC and Everton FC is the longest running derby in the highest division of English football and is based in the city of Liverpool, England. The name “Merseyside” comes from the river Mersey that runs through the city. Unlike Celtic and Rangers who are on opposite sides of town, or FC Barcelona and Real Madrid who are on opposite sides of the country, Liverpool and Everton are practically within earshot of one another; you’ll spend more time looking for parking around Stanley Park — which separates the club stadiums — than walking the 400m from one stadium to the other.

Anfield in the foreground and Goodison Park in the background, separated by Stanley Park | Source: © Liverpool Echo

One of the reasons why this derby is called the “friendly” derby is because unlike our first two examples, Liverpool and Everton were originally one club. Everton FC was established in 1878 and originally played at Anfield, the stadium that Liverpool plays in now. This unity lasted for more than a decade before several club board members — fuelled by political differences regarding prohibition — decided to leave and take Everton with them to a new stadium called Goodison Park. What was left at Anfield became Liverpool in 1892. This shared history, as well as the extremely close proximity, meant that there was a collective ‘Scouse’ identity that existed within the liminal space occupied by both clubs. A common phenomenon is that different members of one family support either Liverpool or Everton. During the Merseyside derby, the rivalry intensifies, but once the 90 minutes are up, supporters of both sides go home (sometimes the same home) and celebrate both a good fight and an even better fraternity.

Penned-in crowds during the Hillsborough disaster | Source: © Mario Cube

This fraternity is also bolstered by the collective acknowledgment of the biggest football tragedy that has impacted the city of Liverpool itself — the 1989 Hillsborough disaster. The incident itself didn’t actually occur in Liverpool, but was in the city of Sheffield, England, at Hillsborough Stadium. It was a match between Liverpool FC and Nottingham Forest FC, with a spot in the final of the FA Cup — the world’s oldest football knockout competition — at stake. Naturally, there was an incredibly high number of Liverpool fans who came to Hillsborough to watch the match — and the stadium was not equipped to welcome that many people. Within a few minutes of the match starting, it was clear that the flow management of the fans was very poorly coordinated, and people in the stadium began starving for space. It should be noted that this all happened during the height of hooliganism, and the local police treated many of the fans with that bias in the back of their mind. So instead of alleviating the increasing pressure, they cordoned off parts of the stadium to ensure that no Liverpool fans crossed into the area of Nottingham fans. This created a “penning” of the Liverpool fans — a literal border created by police presence — and a human crush happened. By the end, more than 700 people were injured and 94 were killed, with 2 more dying a few years later after their life support machines were switched off. The 96 who died that day ranged in age from 10 years old to 67 years old, and for many decades the police refused to acknowledge their part in the disaster, instead placing the blame on the fans for their supposed “hooligan” behavior.

This [derby] identity defines your role as a warrior of one footballing side, even though you yourself are not participating in the actual event. This identity is a reminder that you still have an integral part to play in protecting and defending this partisan space.

As a response to this injustice, both Liverpool FC and Everton FC gave their support to the victims of the Hillsborough disaster, aiding their efforts in the court system until, finally, in April 2016, a coroner’s inquest gave the verdict that the 96 were “unlawfully killed [due to] police failures, stadium design faults, and a delayed response by the ambulance service.” This was a significant victory after a nearly 30-year-long battle for justice. Everton’s chairman Bill Kenwright famously said in a memorial service to the tragedy in 2013, in solidarity with Liverpool FC, that “[the police] took on the wrong city — and they took on the wrong Mums.” Unlike the violence that drove people apart in the Old Firm derby and El Clásico, this was a violence that brought people together, albeit with an incredibly tragic cost.

Everton Blues and Liverpool Reds together | Source: © 32 Flags

While other derbies have brought the worst out of people, the Merseyside derby has brought the best out of people, and I think it is because at the heart of this particular derby is a fundamental shift away from the soldier mentality of old to the solidarity mentality of now. No longer is this liminal space — bounded by history, religion, socio-political circumstances, you name it — a territory that needs to be claimed, but is now a communal space to be shared.

If the Merseyside derby has taught us anything, it is that humankind is bound to love confrontation and conflict — we’re dramatic people, after all — but that love can be tempered by an even greater love for friendship and community, even in spite of diametrically opposed views, beliefs, and identities. As I said earlier, we live in a much more peaceful time than ever before — but that doesn’t mean there aren’t people who wish to threaten this peace. If we can learn to sit with an opposing derby fan on derby day, and perhaps even enjoy the passion regardless of who wins, then maybe we can also learn to sit with those we disagree with and create a new liminal space that invites rather than excludes difference and discourse. Maybe then we can finally believe that we do live in more peaceful times.