KELLEY KIDD

Above are just a few of the endless headlines on the covers of lifestyle magazines such as Vogue, Glamour, GQ, and Men’s Health. Nearly every cover out there features at least one headline like this. They include an imperative statement, tell you what you must have and think, advise you on how to be the person you want to me (usually by purchasing something), or inform you that your opinion on something you recently enjoyed is simply no longer accurate. They speak with an unquestioned authority on the subject of how you should look, dress, feel, and want. Their statements carry the weight of everyone’s opinion of you behind them, commanding readers to alter their behavior in order to receive continued approval from the rest of society. Yet, without the participation of their readers, these instructions are nothing more than words written and decisions made by a small group of designers and marketers. The life and death of a trend rest in the hands of an audience to perform its popularity. Its success relies on a complex system of interactions in which each participating player must be both audience and performer.

The Birth of a Trend

It may initially seem as though the performer-audience relationship is a straightforward transfer of information from marketers to market. In this view, “the fashion industry” — a too broad phrase that will here encompass fashion designers, forecasters, and marketers — would present the world with a performance modeling how the market should look and act, and the market would then absorb and repeat. However, the collective audience that makes up said market are also the ones that carry the majority of the weight of actually disseminating information about what is “in” and what is “out” by choosing to recreate the performance presented to them. Because this audience participation is so crucial to the effective enactment of trends, fashion designers and marketers seek to deeply understand their audience first. The fashion industry, as a result, begins as the audience rather than the performer.

The late iconic photographer Bill Cunningham’s street fashion section for The New York Times titled “On the Street” | Source: © The New York Times

Fashion designer, forecasters, and marketers must observe the behaviors of the market in order to understand what aesthetics and ideals will most appeal to participants. Fashion marketers conduct in-depth research surrounding the practical needs, cultural norms, values, and preferences of potential target markets. They consider the economic factors that will shape a consumer’s choice to buy or not to buy. Their voice in the room represents the market forces influencing fashion. Fashion forecasters “are lifestyle detectives: men and women who spend their time detecting patterns or shifts in attitudes, mindsets or lifestyle options” using historical and social information. They respond to bottom-up influences, taking into what trends are beginning to independently emerge in popular culture. They foresee what will likely appeal to people in both the long and short term, essentially adding to the process the information about what we like before we even know it.

Simultaneously — and in (at times conflict-ridden) conversation with this information — designers create clothing and ideas. Designers tend to prioritize the artfulness and inventiveness of fashion, which is crucial to driving change in trends over time. This continuous evolution is central to the “planned obsolescence” that drives the ongoing transition of trends in consumer preferences, which generates a good deal of the industry’s profitability. However, these creations vary in their accessibility to the public and their innovation level, and sometimes the creativity of the design comes into conflict with the market needs of the moment. Nevertheless, these three characters of designer, forecaster, and marketer must first operate as audiences in order to perform their roles successfully.

A brand must understand a market so deeply that it can sell itself as the tool necessary for proper performance of its culture.

Staging the Trend

With their powers combined, armed with information about their audience, these teams shift into the performative role. They determine what fashion will land on the runways, on magazine covers, and in store fronts. These tools serve as the first mechanisms through which a trend is outwardly performed, presenting to the public the available options. In this moment, we see the clearest instance of the fashion industry performing for its audience, the market.

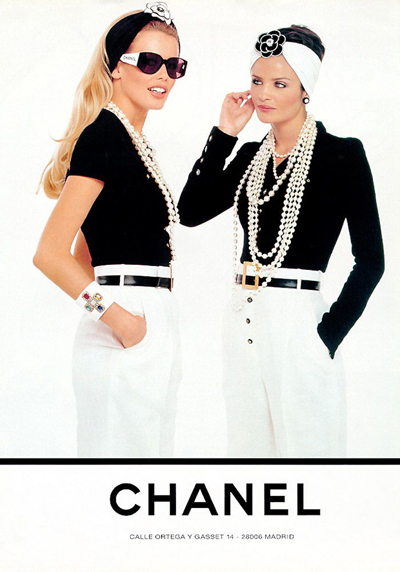

Vintage Chanel ad | Source: Simply Frabulous

Magazines and runways speak directly to the members of distinct social scenes. The market for a particular trend tends to be a group of people who share a culture — who participate in the same kinds of leisure activities, prioritize the same degree of nonchalance or effort in appearance, work in similar environments, and share similar socioeconomic status. The fashion industry provides each of these distinct audiences with a set of images directly associated with each of the factors that make up their identity. If you are this age, this is what you want, magazines instruct. If you like festivals, here is what you wear to be pretty and lovable, dictates advertising. Chanel says nothing and simply presents an image that speaks to the wealthy, and their name itself informs you that wealth looks the way they do. These performances establish the platonic “form” of each culture, informing individuals what represents the ideal version of each persona.

Macy’s iconic flagship store in Herald Square, in 1907 | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Retail settings serve as the mechanism for distributing the physical materials required for a trend to come to life. This requires simultaneously acting as both audience and performer. Fashion marketers try to sell to them in order to distribute their products and trends, rendering them an audience to the fashion industry. Simultaneously, a store or brand affiliates itself with a culture — that is to say, an effort level, an age group, and a socioeconomic status. In order to do so, it must deeply comprehend each of those factors. A brand must understand a market so deeply that it can sell itself as the tool necessary for proper performance of its culture. They must select products that allow us to feel that we are expressing ourselves, connecting us to those who share our culture, and properly signaling our participation in the subgroups relevant to us.

The Social Performance

From here, the performative power over the life of a trend falls into the hands of the audience. Henrik Vejlgaard, a researcher on the life of trends, posits that trends are brought to life by trendsetters. These are the first audience members to transform into performers, and they also tend to be those who have the attention of other audience. They are often creatives, innovators, and people with a good deal of social capital, like celebrities. As these individuals begin to perform new trends, taking the greatest risks and experimenting with new fashion, they indicate to their social circles what performative options are available. In turn, the people around them begin to select their own performances from those choices.

Audrey Hepburn and her Givenchy black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany’s — a scene that brought the “little black dress” to mainstream attention | Source: Wikimedia Commons

As social animals, we tend to position ourselves as audience members to our friends and connections. We seek to learn from them, emulate them, meet their friends, spend time engaged in the activities they enjoy, imitate them, or use them to be closer to what they are close to. We surround ourselves with those whose notes on being we intend to absorb. Those around us are often doing the same, so the flow of information and feedback becomes bidirectional. As information about a trend disseminates from trendsetters to trend-followers, the performer-audience relationship becomes more fluid. As the people around us engage in a trend, we receive the data that this trend is something positive; part of the kind of person we are interested in being. Simultaneously, our performances share other bits of information with the rest of our social circles.The 1995 comedy Clueless, which defined the fashion trend for an entire generation | Source: Wikipedia

The 1995 comedy Clueless, which defined the fashion trend for an entire generation | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Shared social norms and priorities further facilitate the flow of fashion choices between people, since these particulars shape what speaks on both logistical and aesthetic levels to certain groups. In turn, those who want to participate in and be seen as part of a particular section of society will perform the associated trends in order to more effectively participate in that trend. This reinforces the power of those trends, so that more audience members see it not only in their own social circles but also as they walk down the street in certain areas, participate in certain activities, and go to work. Each member of the scene becomes both performer and audience. Individuals view themselves as participating audiences and select performances that will allow them to fit in.

At the same time, however, they contribute to the performance that other participants witness. The whole world in which you participate becomes made up of a performing audience where everyone simultaneously signals to one another what is “in” within that culture. These performative audiences proceed to select from and mimic what they see around them, until a trend has saturated the market to which it appeals. Once saturation has been reached, the life of the trend begins to fade, and the process begins again with something new.

The life and death of a trend rest in the hands of an audience to perform its popularity. Its success relies on a complex system of interactions in which each participating player must be both audience and performer.

Trends exist in a complex ecosystem of players that are all equally performer and audience, participating in a constant exchange of information between consumer and industry. The industry relies on consumer participation and must, therefore, tailor its creation to the interests of its audience in order to succeed, yet at the same time, the audience’s participation feels all but obligatory. The ubiquitousness of trends, their constant flux, and their performance makes it nearly impossible to exit the system despite being as much a part of its enactment as those ostensibly deciding what is fashionable. Each time you select an outfit, you are reflecting the performances you have witnessed and playing a role for other audience members to watch and respond to.