ITUA UDUEBO

The Oxford-Webster Dictionary defines a generation as “all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively.” When you think about the idea of a generation, it’s often as a localized frame to understand history; Generation Z, the Silent Generation, Millennials, etc. Having a way to understand the societal, political, and economic factors that shaped a collective group of individuals helps us understand the events of their time and the ways they impacted it. When you understand exactly what it was like to grow up during the Great Depression and emerge as part of a reborn nation — the kind of commitment to patriotism and service that those conditions cultivate — it becomes clear how the brave men and women of the Greatest Generation stood the test of World War II; when you’re aware of the cultural rot, rampant capitalism and desperation for individual meaning that plagued Generation X, is it any wonder that they turned to detachment and dread as coping mechanisms?

Generations Throughout History | Source: © BuzzFeed Video/YouTube

The concept of social generations — as opposed to familial — has existed across societies for hundreds of years. In the Western World, the practice of generational naming wasn’t part of the cultural conversation until Gertrude Stein coined the term “Lost Generation” in 1924. It was her way of encompassing the aimlessness and collective shell shock of those who’d lived through World War I (1880-1900). After Hemingway quoted her saying, “You are all a lost generation,” in the epigraph of The Sun Also Rises, the term became popularized and a new historical convention was born. What started with Stein attempting to capture the spiritual alienation of those Americans who rejected the provincial, materialistic nature of the country has morphed into a journalistic trope, a cultural sentiment so common that some people mistake their generational identity for a personality trait. Baby Boomers imagine themselves as the men and women who built the modern American superpower through hard work, mental toughness, and a free market zeal second to none. Generation Z understands itself as the next evolution of the productive citizen, a group of people so imbued with technological prowess and activist zeal that comparison to older models is a moot point. The Greatest Generation is held up as a high mark of our culture and national spirit by the pro-military crowd; many an aspiring artist looks to the Beat Generation that laid the groundwork for the 1960’s counterculture, the great thinkers who rejected everything and sought new paradigms. The popularity of these identities is a testament to not only the common human need to belong, but the need to identify with our pasts, understand our present, and manifest our futures. We embrace generations because we embrace groupings and collective understanding, a sentiment which brings us back to the dictionary definition.

With one statement, a person can understand themselves in their own time. You are no longer just a 23-year-old in 2019; you are a Millennial young adult figuring out what being a Millennial young adult means.

“Regarded collectively.”

In the most straightforward sense, to be regarded collectively is to be examined as one part of a whole, a piece of a collective unit. It’s the difference between your boss roasting your entire project team and singling you out for the extra ten hours you contributed to the failed outcome. It’s also the feeling of being part of a championship team, even if all you did was ride the bench all season. Placing the individual within the collective is an act of deletion and alteration, a necessary aspect of sociological thinking that allows for macro-analysis. It’s within the other half of this equation, however, that our interests lie: the objects of this collectivization, the people being grouped.

In the moment when I say that I am a member of the Millennial generation, whether as an affirmative or simply an acknowledgement of being born in 1995, three simultaneous events happen:

- I am understanding myself as belonging to a group of people born between 1981 and 1996

- I am separating myself from people born before 1981 and after 1996

- I am attaching myself to a history of landmark events, political issues, economic trends and cultural shifts that affected people born between 1981 and 1996 in a significant, unique way during our developmental periods

And outside of that immediate moment of identification, in any discussion that involves these generational aspects, my thinking is affected by the following patterns:

- I am contextualizing distant history that came before my own time as the history of different groups, other people

- I am considering the present to be a direct result of that history, and therefore directly attributable to the other people who created it

- I am comprehending the future as something that will be affected by this group I belong to, a collective responsibility that I may or may not have a moral imperative to actively contribute to

These six methods of generational identification form a powerful framework for self-understanding. With one statement, a person can understand themselves in their own time. You are no longer just a 23-year-old in 2019; you are a Millennial young adult figuring out what being a Millennial young adult means. You look towards other Millennials for support and guidance while providing the same yourself. It doesn’t amount to self-understanding but it provides a framework for self-discovery to play out, along with empathy for other members of your generation. Is it any wonder, then, that with a framework this powerful, this encapsulating of so many different human psychological needs, that generational identification is also the source of massive, unyielding tension in our society? And furthermore, is this tension simply a result of outside stress factors and historical revisionism, or is there something inherent at play? Is the tension between generations a cyclical certainty, or a recurring phenomenon that can be mitigated with intervention?

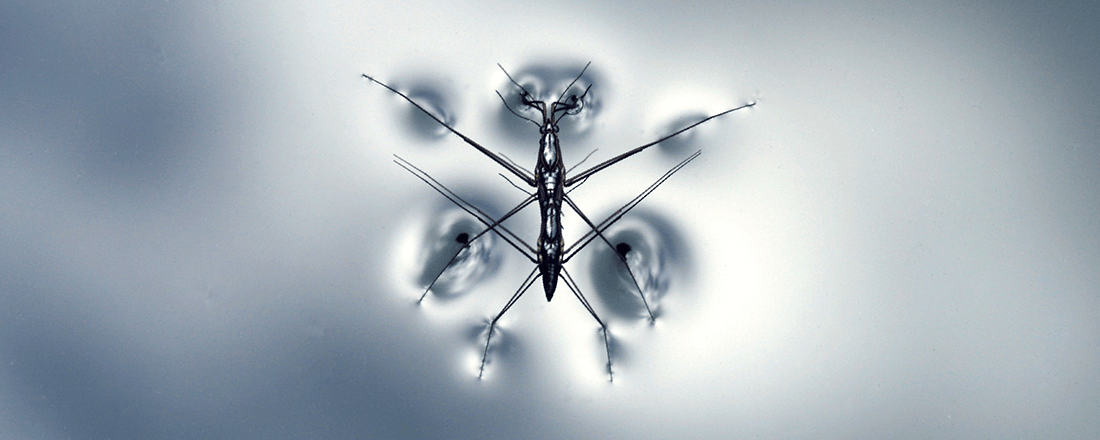

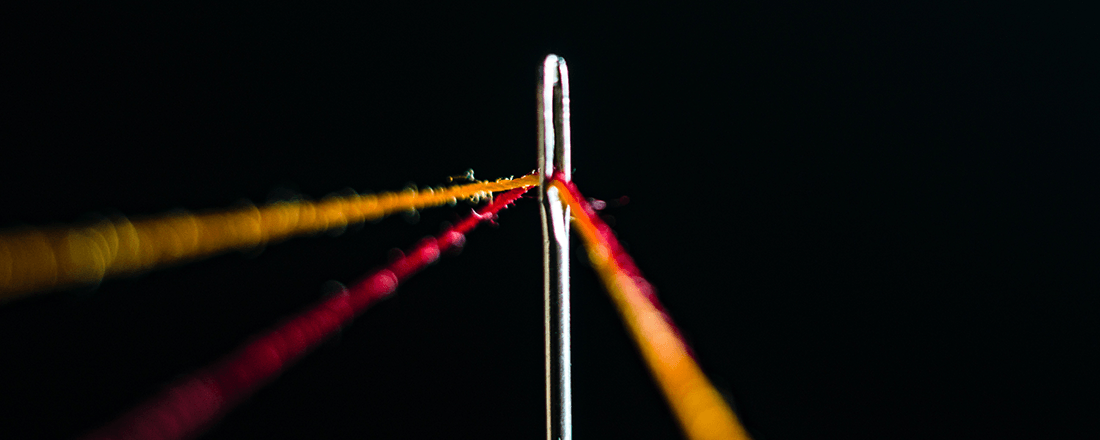

When you hear the word tension, the first thing that likely comes to mind is a state of discomfort. A negative. A stressful sensation. A tense situation is one false move away from disaster; a tense moment seems destined to never end. Tension is not an ideal state of affairs, but for all of its discomfort, tension is also natural. The scientific concept of tension, of a force that exists between two endpoints, is foundational to our current understanding of the universe. From the atomic restoring force that results from atoms and molecules being pulled apart to the pulling force transmitted from each end of string, tension is a constant in our lives. The negative connotation we associate with the concept works for colloquial purposes but it obscures the benefits of a more positive understanding. The endpoints of a string may be distant and destined for opposite directions, but beyond that conflict, they are intrinsically bound by the string itself, two elements of one entity. When you pull a string you create three forces, and the force that exists between two opposing forces maintains the physical composition of the structure. Release the tension by relaxing your pull and all force vanishes; end the tension by breaking the string and the structure is destroyed. In those moments of tension, forces exist beyond the string itself, and it’s within that tension that a relationship exists as well.

Having a way to understand the societal, political, and economic factors that shaped a collective group of individuals helps us understand the events of their time and the ways they impacted it.

As we examine generational tension, it’s important to reframe our understanding of the way tension manifests itself in our lives. It’s important to remind ourselves that an uncomfortable sensation, just like fatigue or heat or cold, is not something to be avoided at all costs. We have to deal with it. And we have to re-examine our experiences with generational tension in light of the relationship that exists within the forces at play. These other groups — these generational antagonists — are our mothers and fathers, grandparents, and, on occasion, siblings, and no amount of tension along generational lines is strong enough to break the bond that holds people together.

It’s important to remember all of this. But not always so easy.

When I was sixteen years old, my maternal grandma came over from Lagos to stay with us for a summer. She hadn’t been to the States since I was ten, and on that occasion she’d only stayed with us for a week as part of her month-long trip to the States. She had three children to visit and three sets of grandchildren to spoil, with New York as her first stop, providing me with what I can safely say was one of the best weeks of my life. As a professional baker, she considered it her duty in life to produce a miniature mountain of sausage rolls, meat pies and rum cake every day, and I considered it my responsibility as a loving grandchild to gobble them up. She brought over traditional clothes, lovingly bothered me to help her with the simplest tech problems, and shared stories of growing up in Nigeria back when it was a colony of the British Empire, which I remember finding both fascinating and deeply upsetting. I had fond memories of that week, and as a more fully grown teen, I was looking forward to spending more time with my loving, warm, baked-goods-machine grandmother… and then the first lecture came. And the next one, and the one after that, and the one after that, and so on and so forth. Life lesson after life lesson about how I needed to be a good son and bring honor to the household; about how spoiled we were after all the years of American living; about the clothes I wanted to wear, the friends I wanted to see, the music I was listening to in the privacy of my own earphones. It wasn’t as if I didn’t get an earful on these topics from my parents on a regular basis, but that had become such a routine that it hardly registered. This felt like some kind of deception, or better yet, an unveiling of a new reality where my grandma and I couldn’t find a single thing in common or have a single conversation that didn’t end with a semi-scolding. And in turn, the simple affection I’d had for her as a child turned into a far more complex set of emotions.

The love was all still there, of course, and the warmth in her smile. She still shared stories of her life, which I was able to interpret in new, developed ways, the life lessons she was imparting finding far more receptive ears than her speeches. Even the baked goods were still present, albeit with a far more restrained consumption rate — even as a defensive lineman, varsity football requires a high amount of nutritional discipline, and daily cupcakes were not part of the equation. She was the same woman I’d remembered so well, the same person, but I’d experienced some critical changes. Outside of the typical nonsense of puberty (which is a topic for another, more traumatizing day), I had developed a set of distinct behaviors and mentalities that can be traced to my generational identity. She was already bothering me for IT assistance when I was 10, but by the time I was 16 she viewed my social media habits as something to be chided rather than utilized. I still practiced deference to my elders and performed housework without complaints, but my disregard for traditional greetings and etiquette bothered her immensely. She was stuck in her ways and views, and I was growing into my own.

When it comes down to it, generational tension is a fact of life, and like all things in life, it can be good, bad or non-existent.

All the little things about who I was becoming. All the little parts of me that were pulling away towards a new direction. They also countered all the little things about her that had already been shaped by her life and times. Two endpoints moving farther and farther apart, separate but not separated. A strong tension that held us together throughout those changes, and will persist for all the changes I’ve yet to go through. I love my grandmother — a statement that I hope should go without saying–and that tension, that generational divide, doesn’t stand in opposition to that fact but rather alongside it. That tension is a fundamental element of our relationship, and even during the less pleasant times, that relationship is strong. As long as the string remains intact, tension is nothing to fear, and can only serve to make it more beautiful — after all, what good is a loose string in a piece of cloth?

When it comes down to it, generational tension is a fact of life, and like all things in life, it can be good, bad or non-existent. Good tension keeps the string tight; bad tension breaks it apart; non-existent tension keeps it from achieving maximum force output. Where generational tension exists, it manifests itself in unique ways, but it always stems from the same natural place. In order to answer the question of whether generational tension is cyclical, we need to look at settings where the phenomenon is prevalent and see how it manifests, whether or not it’s mitigated, and if it’s possible to erase altogether.

There was one time during that long summer where I was getting ready for a “date” (I thought it was, she thought it wasn’t, real fun time that was) and my grandma started in on something about getting into trouble with girls, a topic I had neither the time nor life experience to engage with. After avoiding a series of awkward chats with my mom and one fumbled “When I Was Your Age” story session from my dad, I’d be damned if it was my grandmother that trapped me in a conversation about my love life. When it comes to subjects that don’t span well across generational lines, sex and dating have to be near the top of the list. Depending on the culture your family is part of, the topic is either understatedly uncomfortable or forcefully forbidden. Sexual behaviors and norms, across times and societies alike, are no stranger to fluidity and change, and while that evolution and conversation continues to unfold, the tension that forms the bedrock of it continues to create a force that binds us in our common sexual nature. In any given community or family setting, one can find a bevy of individual sexual sensibilities on all topics, from arranged marriage to polyamory. What our parents valued and what our children value when it comes to sex and relationships, even if it converges with any individual beliefs, is/will be shaped by factors and trends that don’t apply to us.

Outside of the natural sex drive, the influence of society and culture is the primary determinant of sexual norms of behavior — those change over time, resulting in a natural tension over what’s appropriate and healthy. In my grandma’s time, the concept of dating didn’t even exist, at least not in a way so open that it had a name, and proper courtship was done only with the intention of producing a proper Christian marriage. My experiences with dating have avoided the “M” word like the plague and fall all along the wide spectrum of commitment. Premarital sex was a special level of sin back in her day, especially for an upstanding young lady like herself, whereas I’ve [redacted for personal, conversation-avoiding reasons] and cohabiting before marriage is an expected behavior. The conflict is drawn across lines of propriety and shifting norms, which means that the generational tension on the subject is heavily backed by social reinforcement, making mitigation even less possible. It’s exactly in the nature of that conflict, however, that we find the synthesis of values that makes the cyclical tension a benefit born from an uncomfortable state. As much as I might fully embrace the freedom of the app-facilitated, new-person-a-day dating culture (would it be too on the nose to mention that I’m writing this right before heading out to a Hinge date?), there is something to be said for the amount of dedication involved in the kind of courting my grandfather had to pull off to find his soulmate. That doesn’t mean I’m going to start visiting girls’ parents every weekend, but it does make all the running around we get up to these days seem a little more shallow in comparison. And while my dad might still have hope in his heart that my sister won’t be dating until she’s married, he’s gotten much more comfortable with the notion of dating in the first place, and certainly better with noticing the double standards that abound in his understandings. That better place where both sides arrive at is the result of tension, and when generational differences are put aside in the name of coming to better, healthier terms with one of life’s biggest mysteries/joys, it’s a cycle that continues to provide us with positive outcomes time after time.

It’s important to remind ourselves that an uncomfortable sensation, just like fatigue or heat or cold, is not something to be avoided at all costs. We have to deal with it. And we have to re-examine our experiences with generational tension in light of the relationship that exists within the forces at play.

Another realm where generational tension comes to light is, of course, the workplace. Or at least our views on work ethic. My grandmother is the daughter of a well-regarded community elder and a phenomenal homemaker, and she’s been a successful bakery owner for most of her adult life. Suffice to say that she knows a thing or two about hard work. Another thing she knew about was calling us lazy whenever any task was done with less than 500% effort. Again, this was one of those refrains I’d heard from my parents a million times over which somehow found a new sting from my grandmother. In terms of any generational tension, her statements on work ethic didn’t mean too much at the time given that my grades were good and housework was a fact of life, but they started to take on a new meaning when I entered the workforce. While one would naturally think of family as the most prominent setting for generational tension to play out given the built-in dynamics, the workplace sees it more often and in more extreme forms. Unless you work in Silicon Valley, yet another startup, or the unknowns of self-employment, chances are the age dynamics in your office involve senior employees being older than the people they supervise. This follows just about every rule of logic; experience comes with age, and the responsibility of leadership should follow suit. The old master leading the young apprentice has been a social archetype since the dawn of skilled labor, and so we understand the connection between age and knowledge as a natural fact. What does this mean for the generational tension of the workplace? This tension manifests as different styles, thought processes and methods competing for validation through success. Our approaches to work are a product of our individual upbringings, educations and collections of professional experience. Outside of the basic workplace truths — work hard, take pride in your craft, don’t black out at the holiday party — everything is improvised, and the choices we make reflect fundamental generational divides in values. Do you work better as part of a team or as an individual? Do you take pride in paying your dues or do you expect to be rewarded for excellent work in your first few years? What does leadership look like to you — teaching others the correct way to do things and ensuring their success, or giving them the freedom and motivation to innovate and thrive? Wherever you might land on these questions, part of that answer was decided for you at birth, which might be a dramatic way to frame one’s age but an accurate one nonetheless.

Generations that grew up valuing community are bound to hold teamwork in the highest esteem, while those who grew up in more individualistic times will understand its necessity but believe in their own power to affect change. While it might have been bad form at one point in office culture to demand the biggest opportunities in your earliest years, in this day and age anyone without that kind of ambition is doomed to career stagnation. Whatever means and strategies one generation finds the most effective, another is likely to find either offensively outdated or just downright offensive.

How to understand power – Eric Liu | Source: © TED-Ed/YouTube

The workplace setting creates endless opportunities for generational tension to sprout because it requires a constant amount of interaction between value sets in pursuit of the common company goal, but it’s that same unifying motivation that provides the mitigation factor. Any good manager knows that the best way to keep a multi-generational office is to focus on the tension as a source of synthesis. If my grandmother and I had to work in the same office, which I imagine is just one of many forms my own personal hell could take, then the entire focus of our tension would shift. Instead of her fixing the countless problems present in her progeny, she would be telling me all the ways I could be more productive and beneficial to the company, which is indirectly how beneficial I am to her paycheck. The market economy mandates the intersection of ideas and perspectives to create a sum that’s greater than the whole, which leads to more personal and group gain; after all, incentivized individuals have a way of getting over group biases. That tension generates the force that can lead to discussion, which leads to takeaways, which lead to plans of action and new results. The mentor-apprentice relationship is an archetype because of its cyclical nature, and the same can be said of the tension between those two ends of the string. It’s rooted in a foundational logic and manifests in an equally logical way: new ideas and old ideas combining and clashing to create better ideas. As any good manager will tell you, results are what matters, and the results of workplace tension prove that a little bit of discomfort can make a big difference to the bottom line.

Whatever means and strategies one generation finds the most effective, another is likely to find either offensively outdated or just downright offensive.

The only thing that remained consistent between my grandmother’s visit when I was 10 and the summer I was 16 was the 6 years of further mind-phone integration — I was more useful for IT needs. Consider the fact that, aside from her age, she also has servants that take care of things like this for her on the day-by-day. Every little issue with her phone, anytime she wanted to change a TV setting, every time she made an attempt to navigate the Internet, I was on call. Lucky for me she was never ambitious enough to try out the family iPad, but there was more than enough to keep me busy. Technology is probably one of the most clear cut examples of the cyclical nature of generational tension because the idea that informs it is the simplest to understand: progress moves forward. Old tech dies and new prototypes are built every single day, everywhere from your young entrepreneurs to the underground geo-dome below Seattle where Amazon keeps their R&D department. And of all the technology one could use to underscore this fact, the greatest remains the one I’ve been using to randomly check my Facebook timeline while writing this because that’s just the way my brain works now.

The Internet has changed life on this planet in ways that defy comparison. To think that just as little as 20 years ago, people’s access to information was limited to their physical realities is terrifying on a level it shouldn’t be but still is. If I want to know something, anything in the world, all I have to do is go on my phone and ask it. Where to go, what the weather’s gonna be, who had the seventeenth-highest-selling album of 2004 (Metamorphoses by Hilary Duff, in case I didn’t date myself enough in this piece); with full blown university level course material offered online for free, my ability to learn is limited only by my effort and copyright attorneys. This is the world I occupy, and as perfectly as that makes sense to me, imagine how little sense that makes to someone who saw the advent of online in their later years. Crazier still, imagine how little sense my relative awe with the Internet makes to someone who’s only ever understood 5G data and handheld computers as just another thing that exists, like sticks or rocks.

Teens and elders bridge generation gap and digital divide | Source: © PBS NewsHour/YouTube

The generational tension centered on this technological divide is unique because it’s the only area where the common ground is this clear: everyone knows that the Internet is useful and is only getting more useful. Every time your grandparents forget that they don’t need to yell into the webcam to make it work, it’s another example of people far removed from this tech age of ours embracing new ways of doing things. More importantly, the technological divide can result in opportunities for bonding across generational lines; it took me years to realize that what I saw as constant intrusions into my FIFA time in the form of tech requests were probably the majority of time spent with my grandmother, three-minute interactions that meant far too little to me and far more to her than I’ll probably ever know. The technological conditions I’d grown up in didn’t diminish my need for personal interaction, despite what Boomer Internet comics might say, but they did alienate me from the importance of those moments, the essential nature of those small memories. If I had to pause my video games and get off the phone a few hundred — or thousand — times to help her out and give her the time she needed, then the result of our generational tension on technology was a stronger human bond, and that makes it all worth it.

The tension around technology comes from two distinct but related places: the fear of obsoletion, and the rejection of antiquity. The tension that surrounds the Internet comes from the deepest, most subconscious part of our group instincts, that what is here now exists against what was here before, and in line to be destroyed by what comes after. What’s the other thing everyone agrees upon about the Internet? That we simply can’t stop using it. It’s one thing to be useful, it’s another thing to be addicting, and that outcome is a fear that exists both outside and because of that tension. If you’ve went your entire life doing things a certain way, and then one day you’re presented with an amazing thing, and then told that your only two options are to fully adapt to this new thing or be left to the wayside, some natural resentment is going to build. At the same time, if your entire existence revolves around the amazing thing and then the people of authority in your life deride it as symptomatic of your generation’s problems, you’re going to lash back and mock their ignorance. It’s a cycle that follows one of our most fundamental, clichéd truths: we fear that which we do not understand.

Is the tension between generations a cyclical certainty, or a recurring phenomenon that can be mitigated with intervention?

Generational tension occurs when we identify as members of a group, understand ourselves as belonging to that group, and then use that as a filter for how we interact in the world. Whether it’s in the office, in awkward conversations with your mom about your dating life, or as you try for the millionth time to explain how VPNs work, the forces that create this tension are present and constantly at work. Generational tension is cyclical because it relies on fundamental truths about how we view the times we live in and the people we are, but just because it can’t be stopped doesn’t mean the attempt should never be made. If we start to reframe our view of tension as a binding force, as the only thing keeping the string upright, then maybe we can start figuring out how to bridge the gaps it builds in the process. If we can all start to meet each other halfway, across the battle lines that change by the decade, what happens after that might be better than any one generation can imagine.

As long as we don’t rip each other apart.