T. CHASE MEACHAM

Source: Swedian Lie

The rules are:

- Do NOT interact with anyone unless they interact with you first. IF they do, keep the conversation as short as possible.

- You will NOT have you a collection bucket. IF anyone leaves you money, we’ll donate it.

- Someone WILL be watching you the whole time. IF the performance needs to end, we’ll end it.

I was directing a friend in a play I wrote, called Polk Street. His character was homeless — a sort of ghost of the play who appears to the characters, and the audience, as a representative of the soul of the street that had left him behind. He had been a sex worker, and a successful one, and by some account made about as much on his streets as any of the shop owners did.

His relationship to the audience was more intimate than the rest — twice in the play the audience becomes his John, as he edges them to climax. He’s caring and he’s gentle, and he never gives up on the folks who left him behind.

We had the idea that he could interact with the audience early. Ahead of schedule, by positioning him — in costume — on the street, on the outside of the building. That the audience would walk past, and see him (or not), and enter the theater. And then, moments later, encounter him again as a half-way familiar figure walked past, ignored, forgotten, and remembered.

We had the idea he could begin the performance before the performance began, to an audience unaware they’d walked past the show. And so, to cover our bases, we gave him rules.

Consensual Performance

Informed consent is discussed a lot, as well it should be. In medicine, in sex, and occasionally in art that tip-toes past a point of implicit understanding. Most performances, traditionally, are performed in theaters. And theaters are laden with given contracts. Most audiences enter theaters very much knowingly, with tickets that they’ve purchased and certain expectations. And in most performance spaces, it is glaringly apparent which space(s) are for audience, and which are for performance.

The space for the audience may have chairs.

Maybe there are people who direct the audience to their seats. They usually are wearing special clothes.

Cell phones are no-nos, as is talking or texting or unwrapping hard candies.

In other words, the audience has rehearsed their parts as well. Most know their queues and directives, and are pretty cognizant of when the performance begins and ends. Both the audience and the performers are exercising learned behaviors derived from rehearsal. Except for the audience, breaking character is not so much forgetting as it is transgressing a social contract — one that dictates precisely the way an audience is and is not supposed to react to staged performance.

All of this works because the performance, oftentimes, is rehearsed and safe. Enough so that the audience does not need to react, even if they’re worried about themselves or the fates of the characters. The audience knows not to run up and save Hamlet from his death because it’s fake, and the actor’s fine. What happens in the performance space is rehearsed imagination and learned disbelief, and all plays — onstage, or off — are in on the game.

But it also works because the audience knows, and consents.

But what if the audience is unsure of the rules. What if an actor asks a member of the audience a question. Does she respond? Does she stay quiet? What if the performer touches her, or invites her onstage? What are the rules then?

What if there are no seats, and the performers and audience members are next to each other, without clear delineation?

What if she didn’t purchase a ticket? What if she isn’t aware she’s entered a performance?

Does she need to be told?

Interrupted Performance

In other words, the audience has rehearsed their parts as well. Except theirs are learned behavior, and breaking character is not so much forgetting as it is transgressing a social contract.

About an hour and a half before the play began, we began our outdoor performance.

We had discussed the rules with the actor and staked out the space. I took my spot on first watch, and the actor got into place. He was in costume (his hair had been dyed a brilliant golden-yellow). He had no collection cup. The air was cool but not cold; he was wearing a light jacket and torn jeans.

And he began to perform homelessness.

It was a city sidewalk in West Georgetown, the terrain of students and wealthy residents removed from D.C.’s main drags, and comfortably sheltered from more blighted pockets of the city.

It was a neighborhood where pretty much everyone is fine, in a city where many are not.

He began to perform homelessness in a city where many people live homelessness and few people care. Rare is it to see someone stop and give a dollar to a person with a cup, let alone have a conversation, ask a question, or offer help. Encountering homelessness is its own learned behavior, and for many, the reflex is cold, apathetic disengagement.

And living homelessness is a bit like being an actor, in that way — everyone knows your part and everyone knows the rules but no one wants to participate. Many choose to remain bystanders, stepping clear of those who perform their desperation on the sidewalk, lest they become a part of the show.

We imagined the same would be true here, for our actor on the street. Would anyone stop? Who would? Best-case scenario, a couple folks would recognize this person who they passed on the street as the performer who begins the show, and would possibly reflect. Worst-case scenario, no one would notice, or care, or remember.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The actor began his performance as planned, with me watching. To our surprise, it was only minutes that passed before someone stopped. A woman who’d been walking by was leaning over, trying to engage the actor in conversation as he kept his head low, face to the sidewalk.

He was obeying Rule 1.

She wouldn’t go away.

A few minutes later, someone else walked by and left some money on the ground.

Then someone walked by and took the coat off their shoulders, and wrapped it around him, and walked away. The first woman was still there, now scribbling out a check in her checkbook (I don’t know for how much), and someone else, it seemed, had dialed the police.

Spontaneous Performance

What happens in the performance space is rehearsed imagination and learned disbelief.

All of this is fine because the audience knows and consents.

But what if the audience is made unsure of the rules?

One of the most powerful ways to stage performance is outside of traditional space. If you remove the theater and the stage and the seats, and the ushers and the tickets — if you unburden an audience of the context and expectations of traditional theatre, then performance can become something dynamically organic.

It can be unexpected, delightful, or dangerous. Political or provocative.

Source: Nationaal Archief/Flickr

Guerrilla performance can be used as protest. Political rallies are among the oldest and most recognizable acts of impromptu performance, where one or more actors assemble at a given place, on a given time, to build a performance out of nothing. Some are planned, some impulsive. The power stems from engaging an audience who, often times, neither purchased a ticket nor planned to attend. They have been transformed from bystanders to spectators to audience. Except where most audience are keenly aware of their own roles, such is not always the case where performance is unexpected. Audience reactions become less rehearsed and more authentic; less rote and more organic.

A performance given becomes a performance returned.

Argentine performance artist Marta Minujín in a 1965 Happening titled Reading the News | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Then there are Happenings, a vague term for an abstracted performance that is multi-disciplinary, non-linear, and connected to environment. They can involve one or more actors. One or more spectators. About the only thing they do not involve are seats, stages, or constructs, the standard trappings of traditional performance where the audience is in on the rules.

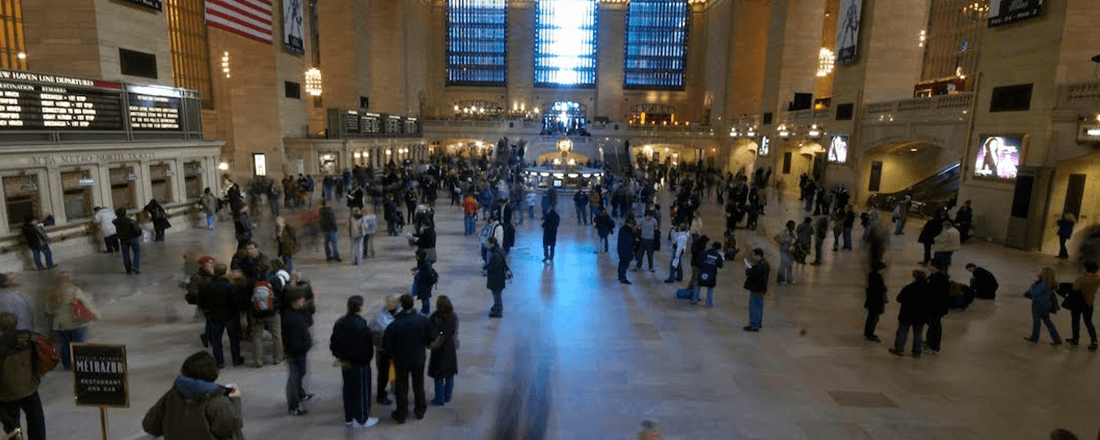

The popular descendant to the happening is the flashmob, a common meme of the 2000s in which a spontaneous, heavily-choreographed dance numbers burst into life alongside thunderous acoustics in large public spaces. Most of these begin with a bang, as a handful of performers emerge from a crowd to an omnipresent beat. The audience is surprised — and certainly, did not plan to attend — but all are immediately aware that they’re part of the show. The audience are aware that they’re spectating, and tend to define for themselves the playing space from the performance space. In that way, though unexpected, many flashmobs become much the same as any other show in any other space (except, of course, that recording is fine).

More interesting is the flash mob where the audience isn’t in on the joke, such as Improv Everywhere’s famous 2001 “Frozen Grand Central,” where over 200 ‘agents’ froze in place in New York City’s Grand Central Station as hundreds of bystanders walked past. Some folks noticed that something was up, but others did not. There were no sound cues to betray that a performance had begun; no naturally-defined delineation between performers and audience. Just 200 people, amid hundreds, who suddenly began acting under a different set of codes than those around them.

Frozen Grand Central | Source: © Improv Everywhere/YouTube

What separates Improv Everywhere from a flashmob is that actors play their roles straight. No breaking character, and no betrayal that they’re performing. But without an environmental queue, who’s to say the show has started? It falls upon the audience to first observe that something about the environment has shifted, and then to observe that is has shifted among so many people in so similar a way, that it must be coordinated. And then, for what end? Are a number of strangers behaving unnaturally to surprise and delight me? Or perhaps something more sinister?

Just a few weeks ago at a resort in Costa Brava, an attempted flashmob backfired when a group of improv players (unrelated to Improv Everywhere), pretending to be paparazzi, were mistaken for terrorists.

In most meme-worthy flashmobs, everyone’s in on the joke, and everyone knows a performance has begun. Everyone can relax and enjoy and take pictures. But in some instances, when the both the beginning and end of the performance is ambiguous and the actors don’t break character, the stakes get higher and the joke’s on the audience.

Profound Performance

An audience that does not know the performer will be okay, [and] may do extraordinary things in their own performed response.

One person was now writing a check, and another calling the police. This situation was no longer safe, let alone expected. This was Rule 3. This performance needed to end, and I needed to end it.

I rushed forward to the actor and the people around him.

“This is an actor,” I stammered.

“We’re doing a performance about homelessness.”

They looked at me.

“He is not homeless. This is a performance…”

They looked at me.

“I’m sorry.”

They looked at us, confused, and left. A little numb, we stepped inside the theater.

Very clearly a line had been crossed, and in the process, a performance that had been designed to expose people’s apathy had actually exposed their humanity and my naïveté. The actor felt he had been the recipient of profound generosity, love, and human decency — and in exchange had been disingenuous, and perhaps manipulative.

Performance that’s unexpected can be profound, not because of the artists but because of the audience. An audience that knows its place is staid and artificial. They know to be quiet. They know to clap at the end. And they know the performers will be okay.

But an audience that does not know the performer will be okay, may do extraordinary things in their own performed response. An audience that does not know why the people around them are acting strangely may encounter a confused rush of emotions. An audience that does not know that they are an audience, and which did not consent to the show, can make extraordinary discoveries because they are called only to react genuinely. All but impossible to do when seated with a ticket.

[If] you unburden an audience of the context and expectations of traditional theatre, then performance can become something dynamically organic.

And as such, the stakes are enormous. For any artist in search of genuine reaction from a non-consenting audience, their care must be utmost. In designing this performance, my focus had been solely on care of the actor:

- Do NOT interact with anyone unless they interact with you first. IF they do, keep the conversation as short as possible.

- You will NOT have you a collection bucket. IF anyone leaves you money, we’ll donate it.

- Someone WILL be watching you the whole time. IF the performance needs to end, we’ll end it.

The focus had been on attracting interactions that were brief, on attempting to skirt the ethical pitfall of collecting a disingenuous donation, and on rescuing the performer from the scene should something unexpected happen.

But no thought was given to our audience, whose kindness we had unexpectedly exposed in search of indifference.

All audiences ought to be taken care of, but especially those who do not consent. It’s a near-ubiquitous trope that all shows end with an acknowledgment of the audience — the time when the cast comes out and lets us know they see us, and that they’re grateful, and that all is okay. No matter what we’ve been through together.

So too ought non-consensual performances have an acknowledgment. They must have an “out,” a moment that betrays the coordination and acknowledges the audience. The Grand Central stunt ended exactly five minutes in, when every one of the 200 actors immediately sprung back into life with dynamic precision. It was a final salute that not only betrayed the group’s coordination, but allowed the room to break, breathe, and burst into applause. And like that, finally, everyone was in on the joke.

But designing that breaking point is every bit as challenging (or perhaps more so) than the performance itself. In our case, our sidewalk performance ended in a clumsy, fumbling ejection, due to my own inelegant design.

But for the improv agents in Grand Central, the out was a beautiful, coordinated climax that was simultaneously the beginning, end, and curtain call of a show that hundreds had been watching for minutes.

All audiences ought to be taken care of, but especially those who do not consent.

To perform for an audience that does not consent is not inherently unethical. But there must come a point at which it’s clear a performance has ended, even if wasn’t clear when it started. There must be a point at which the audience can be acknowledged. At which the performers can break character and escape. And at which the audience can get their time to reflect, should they like, on any new bits of humanity learned or experienced at their expense through the course of the show.

Otherwise, it may as well conclude in “sorry.”