T. CHASE MEACHAM

The hottest new trend in tech is messaging — chatting, with words or pictures or video, within the tidy walled gardens of an ever-expanding number of apps and services designed to bring communication BACK to the cell phone. Finally!

Smartphone companies are racing fast into messaging, and the seemingly endless potential when billions of people communicate together. Facebook has Messenger (not to mention WhatsApp, which it bought for $19 billion in 2014). Apple has Messages. Google is jumping in (a little late) with Allo and Duo.

The world’s most popular messaging app as of 2016, Whatsapp | Source: Whatsapp

![]()

A vintage set of emoticons from the magazine Puck, published in March 30, 1881 | Source: Wikimedia Commons

It’s like a nostalgia for days when kids would peck out messages with keys numbered 1-9. When they used “G2G” and “BRB” (this was when back when it was possible to go offline).

They also had “POS” for when mom and dad walked in (this was back when there were desktops).

[Messaging apps] represent a new way to do an old thing.

But messaging apps today are suites of new capabilities and tools, enabling conversations of words, voice, images, and video. All is contained in a running “transcript” — a searchable, reviewable, sometimes-deletable record of everything we type. Included in those tools is a new symbol set — part character language, part code — an evolution from 1-9 to ? and ?.

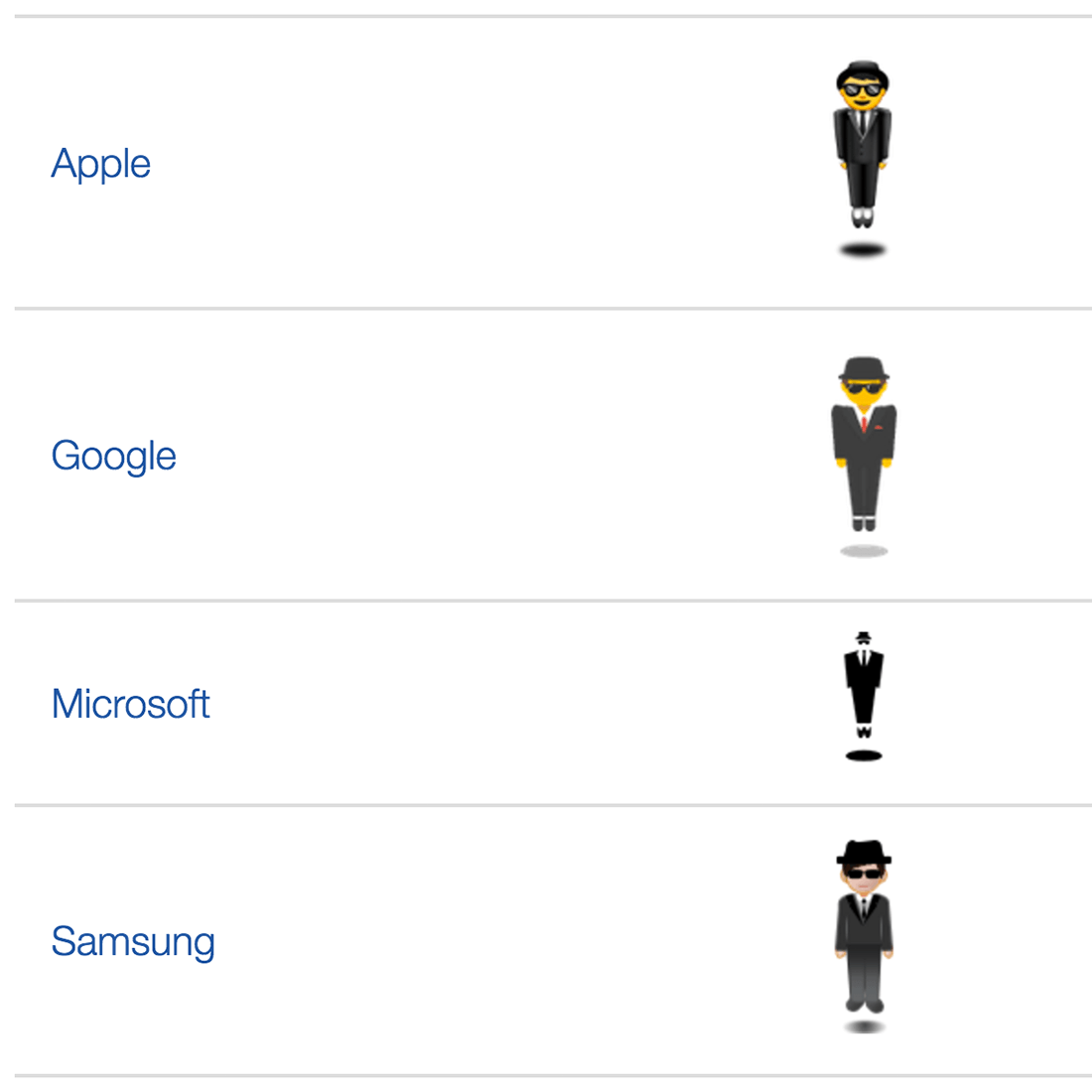

Man in Business Suit Levitating — try using that in a sentence | Source: © Emojipedia

This one to our left, by the way, is defined as “man in business suit levitating.” Kids of today will have no idea how limited we used to be with 1-9.)

Messaging apps, perhaps unsurprisingly, are the most-used mobile applications — more than social messaging, email, Pokémon GO, or Tinder. They represent a new way to do an old thing. A made-for-internet way to pass a note or stage a protest, with the potential to connect billions and the platforms to keep them engaged. Like a concert of actors in communication from all corners of the connected world.

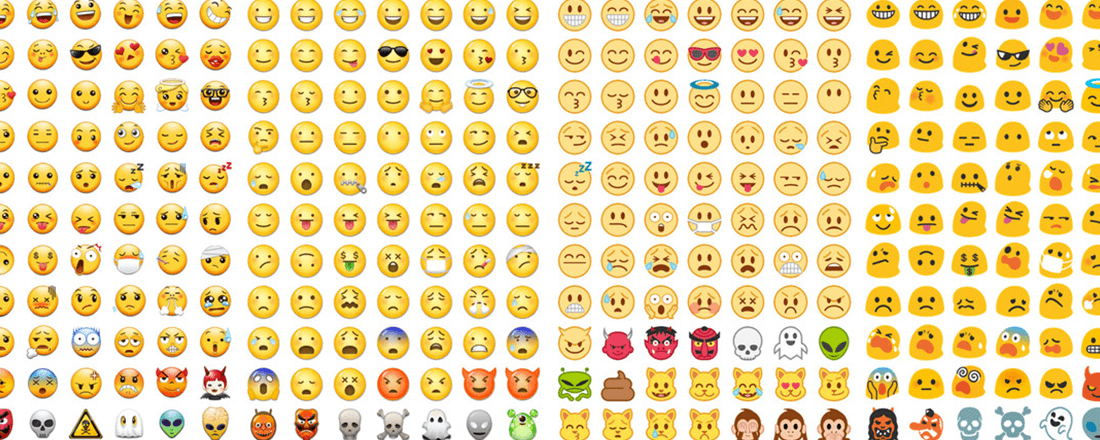

Emojis have been like a delightful accent to this new global conversation. Once an obscure, 1990s-era character set from Japan, emojis have exploded into something of a pseudo-language, with a growing portfolio of characters and expressions to suit a hungry base of newly-native speakers.

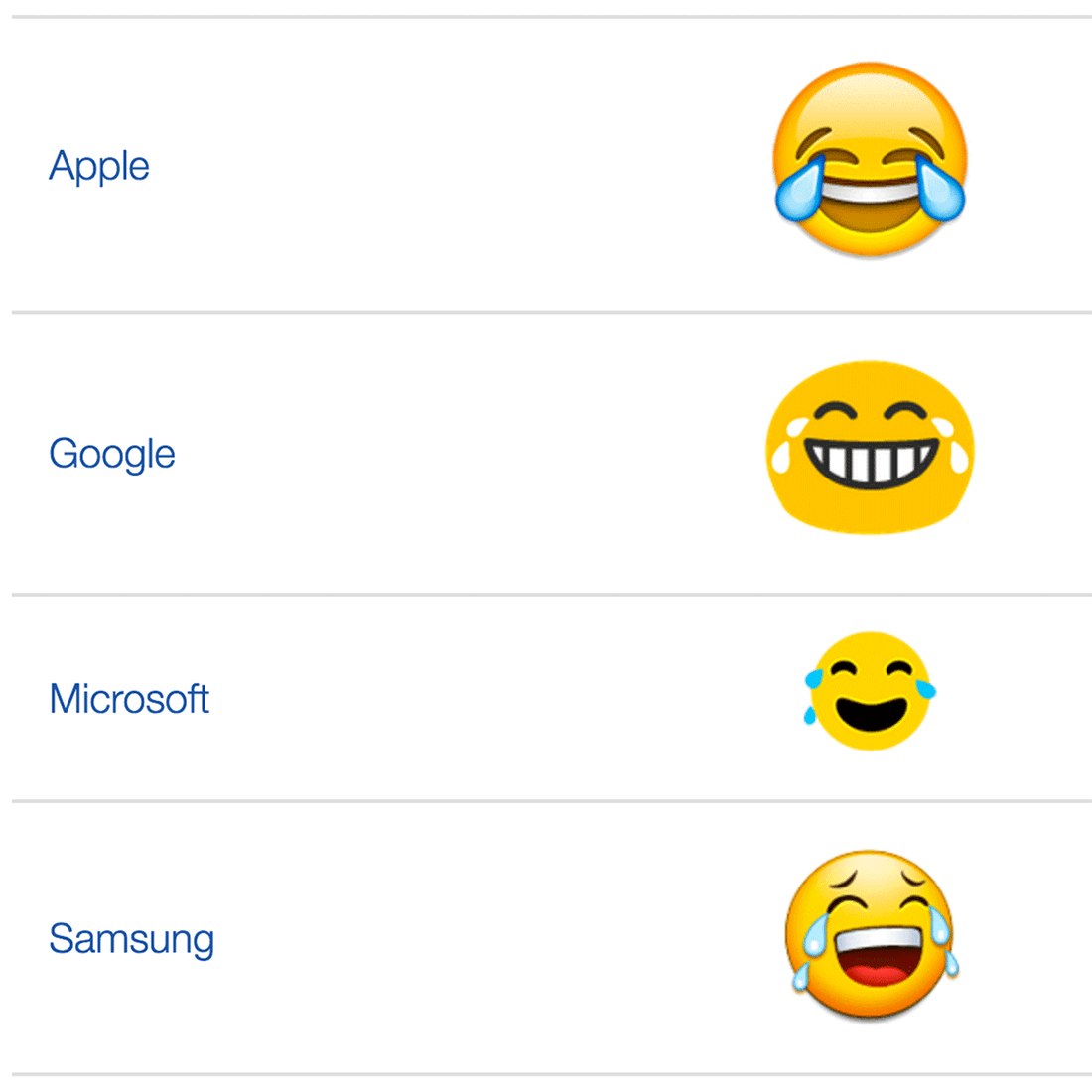

How emojis are rendered across various Android devices, and we haven’t even gotten to iOS emojis… | Source: Android Central

Simple enough that anyone can write.

Powerful enough that anyone can read.

The pictographs took off with Apple’s inclusion of an emoji keyboard as a hidden, opt-in feature buried inside iOS. Now they’re everywhere, on every major mobile and desktop platform. Not as a hidden feature but as a mainstream method of communication. They even picked up Oxford Dictionaries’ 2015 Word of the Year award (?), a testament to an old-school thing like English racing to adapt to words that are neither words nor letters. Sort of like grandparents on Snapchat — sweet, anachronistic, and uncomfortable.

Emoji work because EVERYONE understands the code. It’s not based on characters taught but on characters implicitly understood.

Face with Tears of Joy | Source: © Emojipedia

The winning emoji, by the way, was ?.

But ? isn’t really a word, since it’s not really letters. But calling emoji a character language may also be a stretch. In the newest emoji standard, there are 1,851 official characters, compared to over 50,000 in Chinese and another 50,000 at least in Japanese Kanji (though well-educated speakers of both are estimated to know between five to eight thousand).

Too many glyphs for an alphabet (Latin has 23 letters; English 26; Arabic 28; Hebrew 22). Too few for a character set.

But just enough, perhaps, for casual expression with international capacity. A ? is a ?, whether you call it “caniche” or “פּוּדֵל” or “pudel.” So too a ? a ?, and an ? an ?. Languages only work when two or more people understand the code. Emojis work because EVERYONE understands the code. It’s not based on characters taught but on characters implicitly understood.

Languages also crave standards, so that all users may operate in the system with similar sets of tools. The tools need to be flexible enough such that typographers can add accent, emotion, and nuance to the set — but rigid enough that variants convey the same basic information.

For most languages, standardization in the digital age has come by way of the trade group Unicode Consortium, a 501(c)(3) non-profit made up of big-name tech players like Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Oracle, as well as government ministries, international agencies, research institutions, and others. Its purpose is controlling and regulating Unicode — a widely adopted standard for consistent encoding of text covering over 128,000 characters and over 135 modern and historic writing systems. Each supported character gets a specific code point or sequence, and each operating system reads them identically.

For most languages, Unicode is mostly an index of the letters and characters necessary for pretty much anyone on the planet to have a digital conversation. But for emojis they’re more like a board of governance, charged with keeping the internet’s lingua franca standard across platforms, staying current with users’ needs and reflective of users’ values.

There’s something delightful and performative in reading emojis, because the story you interpret is wholly yours — distinct from the author’s. Distinct from anyone else’s.

Rifles are out; that salsa dancer might be sexist; some people are gay; colors are diverse (careful with those white ones).

Some of the new emoji to be included in Unicode 9.0 | Source: © Emojipedia/Cult of Mac

The earliest Unicode emoji standard (Unicode 6.0) was a combination the early Japanese pictographs from the 1990s and Unicode’s own additions, which have been added to ever since. Unicode 7.0 gave us that man in a business suit levitating. Unicode 8.0 offered skin tone variants (that standard, if you’re curious, comes from the Fitzpatrick scale).

Unicode 9.0 has bacon, clowns, pregnancy, and selfies. Finally!

Whereas old-world languages are defined by users and indexed by Unicode, new-world languages are requested by users, authorized by Unicode, and then standardized.

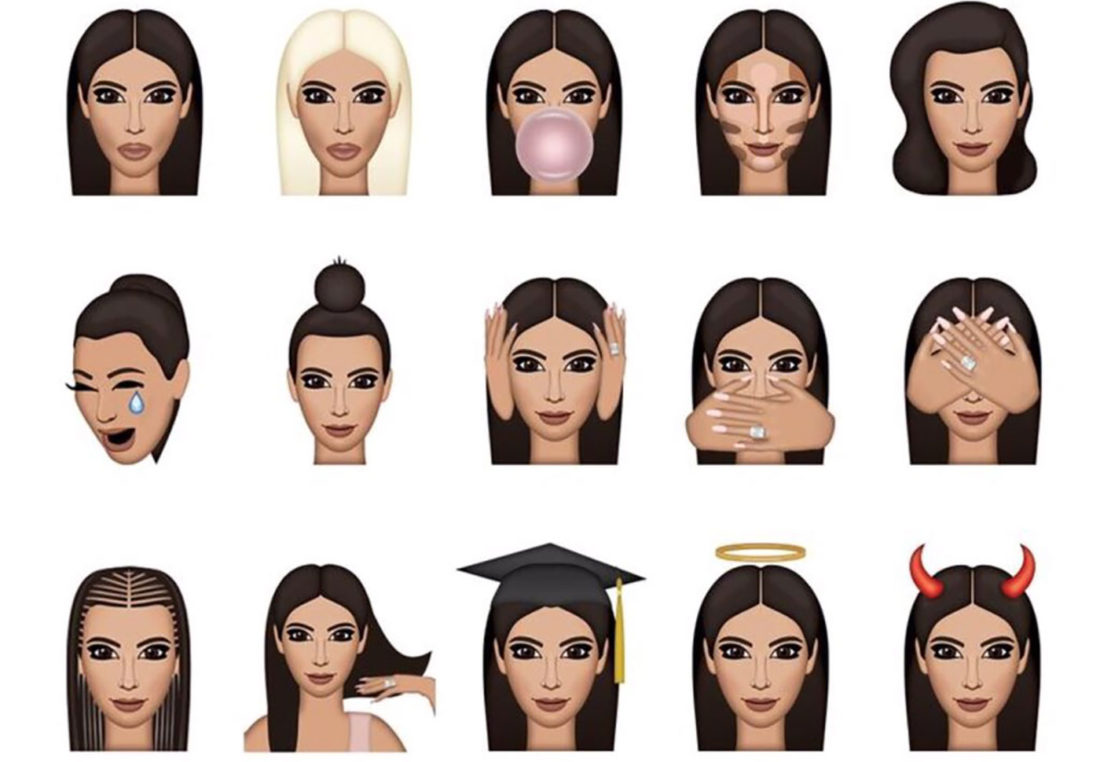

A sampling of the emojis in Kimoji | Source: © Kim Kardashian/Venture Beat

All this makes the Unicode Consortium unwittingly influential, not only as an indexed standard for pre-defined languages, but as the authoritative source of the direction of emojis. Any company (or any Kim Kardashian) can make whatever emoji they like, but if they’re not coded in Unicode, they’re just pictures. Not language.

This controlled release of new characters represents something uniquely modern about communication. Whereas old-world languages are defined by users and indexed by Unicode, new-world languages are requested by users, authorized by Unicode, and then standardized.

But what emojis cannot offer, even with widely-adopted standards, is interpretive consistency. Comprised of instantly-recognizable glyphs, the product of two or more creates a story that no two people will read in the same way. There’s something delightful and performative in reading emojis, because the story you interpret is wholly yours — distinct from the author’s. Distinct from anyone else’s.

For example, in sending you a message about my recent Cancun trip, I could type:

??????

Which you could read, literally, as:

Salsa Dancer • Thumbs Up • Ring • Grimacing Face • Celebrate

Or, more likely, as a story, such as:

I picked up salsa dancing, which, while terrific, makes my spouse very nervous, but in the end we had a wonderful time.

Or maybe:

I recently watched a salsa dancer and had fun — only to discover later that she and I are to be engaged, and that’s great!

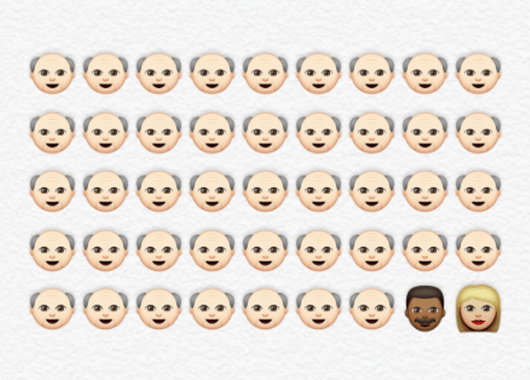

Or take, perhaps, this image below:

One could interpret this glyph set as 43 white men, one black man, and one lady. Or one could interpret this as history.

But within these characters (in this instance, three) is an emotional capacity that, while perhaps not greater than that contained in an alphabet, is likely more expedient.