KATIE ROSENGARTEN

Donald Trump | Source: Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

When Trump announced his bid for the U.S. presidency that devilishly hot day in June 2015, the world laughed. Whether out of genuine disbelief or shock, everyone’s jaw seemed to collectively drop. Was it a joke? A comic bit? More ink was spilled about who would “do” him on SNL than about the political ramifications of a reality TV host — famed for his catchphrase, “You’re fired!” (which has gained eerie application in the past months; @JamesBrienComey…) — who was now angling to occupy a new role, also with its own slot on primetime TV, as the leader of the free world. New Yorker cover artists suddenly broadened their color palettes to include bronzed orange and macaroni yellow. You could almost hear the Stephen Colberts and John Olivers of the world chuckling with the satisfaction of having new joke material. In short, artists did what artists do: represent reality.

[T]he persuasive power of any piece of art lies in its ability to use both the relief of comedy and the gravitas of tragedy to create a convincing representation of reality.

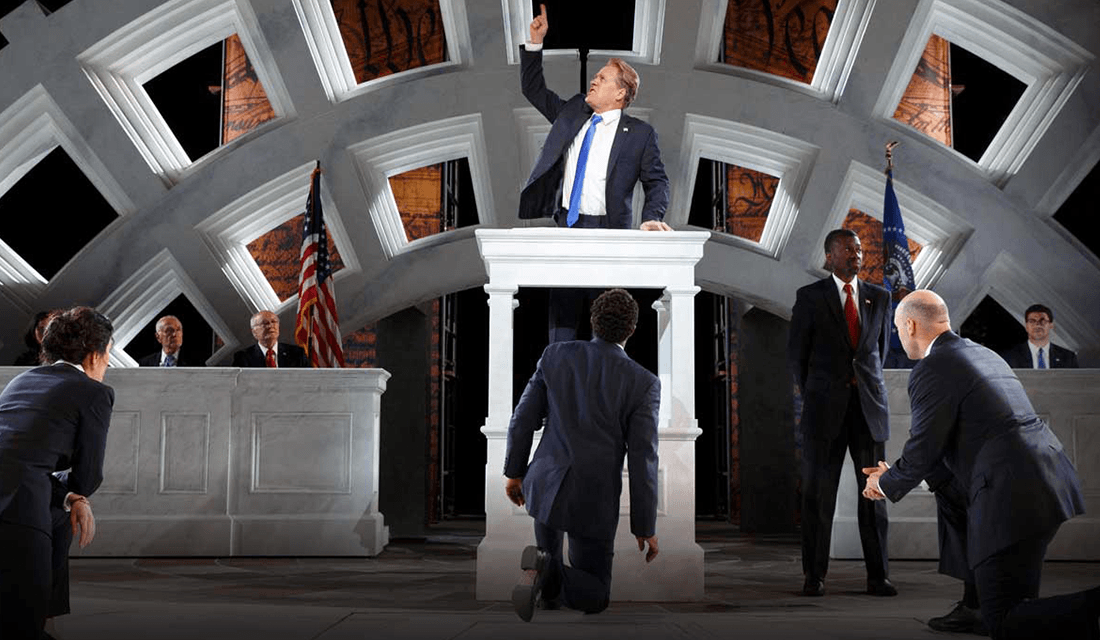

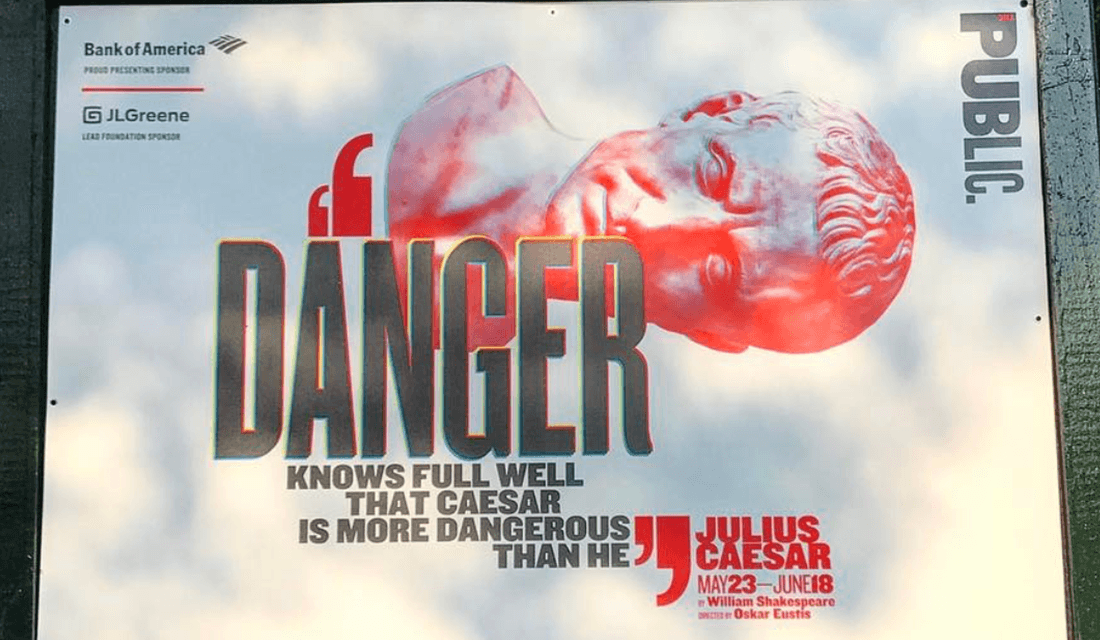

In addition to the slew of late night comedians, theatre companies across the country took up the mantle of representing our tyrannical POTUS. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar became the production favorite to add to companies’ seasonal lineup as a kind of conversation piece in response to Trump’s election — a pointed yet still indirect critique, with all the actors still clad in non-confrontational togas. Oskar Eustis, the artistic director of the Public Theater in New York City, chose to cast the country’s current tyrant-in-arms, Donald Trump, as his Caesar, opting out the usual toga for a power suit, the laurel leaves for a red tie, and coaching Caesar’s wife to adopt a subtly Slovenian accent. I myself have not seen a performance of the Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, so all analysis of the play as it relates to my argument is informed by my reading of various reviews, interviews, and op-ed articles from The New York Times, as well as my familiarity with the play itself and its reception history.

Public Theater’s 2017 production of Julius Caesar | Source: © Public Theater

While deflecting in an interview with the New York Times any direct equation of Julius Caesar to Trump (he retorted, “Julius Caesar is Julius Caesar”), Eustis couldn’t deny the creative and directorial decisions made by his production that led to a stream of right-wing and corporate-sponsor backlash. While any character in a toga with stab wounds will forever be a Julius Caesar, it seems that any character with a backwards toupee, rounded mouth, and tiny hands will forever be a Donald Trump. Policy aside, Trump has succeeded in one very noticeable way: he has created a character type of himself. In that sense, Trump has instigated — even welcomed — a Greek handling of his presidency. Insofar as it is political, it is equally performative. Each executive order guarantees an SNL parody; each diplomacy errand generates a comic strip in the Sunday paper; even each facsimile of political progress, whether a fake bill signing or prolonged handshake, is its own kind of performance, not necessitating any further artistic commentary.

These twin axes of politics and performance were first inextricably intertwined by the Greeks — and most famously by the Athenians in the 6th-4th-centuries B.C.E. It was a combination germane to the very nature of Greek democracy itself. Both political and performative sectors were byproducts of a civilization which — without the luxuries of social media and telecommunication — relied on face-to-face interactions, whether between a buyer and a seller, a politician and a citizen, or an actor and an audience-member. Everything was done in debate-format; even the stichomythic back-and-forth of dialogue in plays staged in the Theater of Dionysus harkened to the political debates that took place just down the hill in the agora. Politics were performative: captivating rhetoric and its key ingredient persuasion were at the heart of any politician’s potential success. Vice versa, political types and events provided ancient tragedians and comedians with roughly delineated outlines of characters that could later be filled in with their singular contribution of dialogue and monologues and costuming.

Theater of Dionysus | Source: Katie Rosengarten

The origins of both were birthed through parallel paradigms of growth: the most important political body in Athens — the ekklesia or popular assembly — served as the pool from which individuals with an aptitude for political argument might arise and eventually join the boule or popular council. Similarly, according to Aristotle’s theories about the development of the Greek theatre, the first performances involved a body of people singing and dancing. Over time, individual members of the choral body got the chance to sing individual arias — a trend which eventually led to the full separation of the chorus as its own entity and a cast of individual actors, at first only one-two and later as many as four-five. Athens was a city composed of equal parts politics and performance, and it comes as no surprise that our culture, most notably our political system — which prides itself on and legitimizes itself through its classical origins — mirrors that of the ancient Greeks. The question of whether a production of Julius Caesar during Trump’s presidency is reflective of the ruler himself is inherently a Greek, democratic question. Yet, Eustis hedges the question by asking: why? Why is a Trump-ed up representation of Julius Caesar a threat to our American democracy?

Trump is a tyrant by the Greeks’ definition, and the artistic community’s impetus to represent him as such also stems from Greek traditions.

Politics and performance alike arise from natural human instincts: on the one hand, to regulate, and on the other, to represent. We try to rationalize and systematize our behavior through laws and rules that we all agree on, mediated through some structure of a social contract. We learn about ourselves and the society that engulfs us by watching others, whether they wear togas or suits or those Shakespearean tights with awkwardly placed stripes. Yet, regulation and rule-binding always generate a mixed reaction; making anyone do anything is an uphill task (just ask your average preschool teacher). Yet, representation is a kind of non-binding regulation of morals and values. By witnessing admirable figures, whose behavior or idioms or costuming either resonates with our own or inspires us to do differently, we are encouraged to act like them. Conversely, when there is a non-admirable character onstage whose behavior either explicitly transgresses legal boundaries, or implicitly stretches the limits of societal norms, audience members are given reign over their interpretation of the actions portrayed.

Oedipus | Source: Albert Greiner Sr. & Jr./Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

The most iconic depiction of a tyrant has been awarded over time to Oedipus, the mythic Theban ruler who not only fathered illegitimate children but whose family was so socially transgressive it engendered its own chapter in Freudian diagnoses. Tragedy is instigated and generically defined by acts of transgression; in this case, Oedipus unknowingly killing his father, Laios, and fathering children with his mother, Jocasta. As Sophocles dramatizes him, Oedipus is a tyrant and a tragic figure: his tyranny stems from his unconventional rise to ruling status, and his tragic nature stems not — as many high schoolers might say — from some “tragic flaw,” but from his subjugation to a series of tragic events which culminate in a peak of, on the one hand, a painful recognition of his transgressions, and, subsequently, a reversal of his fate thereafter. Oedipus’ tyranny, as defined by his ruling status, enables and catalyzes his tragedy; in order for him to fall, he has to start out at some kind of achieved “height” — in this case, both societal and character-based. Not only is Oedipus a ruler, he is an earnest ruler, whose genuine and fierce desire to rid Thebes of its plague instigates his own personal unraveling. As the model of a tragic tyrant, Oedipus challenges the perception of Trump’s tyranny as a tragedy — at least insofar as our artistic community has represented him thus far.

First and foremost, Oedipus’ and Trump’s respective tyrannies differ on a definitional level. The Greek word tyrannos means any figure who gained power through unconventional (i.e. non-hereditary or electoral) processes — a definition which also has strong echoes in today’s reality of concerns over Russia’s possible technological interventions in the U.S. electoral process. Furthermore, we the American public mimic the citizens of 5th-century Athens in our use of performance in weeding out tyrannical figures. With the rise of a tyrant figure as the most central internal threat to Greek democracy, theatre in Athens, whenever it depicted tyrant-types, served as a kind of moral litmus test for Greek society: if any tyrant character seemed too familiar, too akin to a current politician, they could use the play as a political warning sign, a basis for their fears. In that sense, Trump is a tyrant by the Greeks’ definition, and the artistic community’s impetus to represent him as such also stems from Greek traditions. Yet over time, the term tyrant has veered from its Greek origins and taken on evolved notions of a political figure who usurps power for their own power-mongering purposes. Tyrant has become, in some contexts, synonymous with dictator and autocrat. While the solipsistic existence of the tyrant surely matches Trump’s presidency thus far, it also wouldn’t be a misuse of the term to label his rule Trumpus Tyrannos.

Despite its tragic-sounding title, Trumpus Tyrannos is more reflective of the classical model of comedy (thus far; we’re only in Act One). While comedy occasionally used its colloquial power to depict larger-than-life figures like Trump in less lofty, more quotidian guise — such as the demigod Hercules as an insatiable glutton — it rarely depicted, or structurally relied on, tyrant characters. Ancient comedy was “an imitation of inferior people,” a represented reality in which everyone was vulgarized and popularized — one distinctly different from tragedy’s periphrastic, elevated tone. Aside from aesthetic differences, tragedy’s structure, going off of Aristotelian theory once again, was driven primarily by plot, not by character. While we don’t know whether Aristotle thought the opposite was true of comedy (even though he does note a reversal between the narrative structures of tragedy and comedy) there is significant evidence in both ancient comedy and modern satire for such a reversal. In that sense, Trump’s rise to power fails the tragic criterion of the primacy of plot over character. We first met Trump as an already caricatured version of himself, and it was the convincing portrayal of that character that later led to policy promises. It is tragedy’s prioritization of plot that allows a tyrant like Oedipus to garner sympathy, to win over those witnessing his pain and catalyze the cathartic cleansing within them. Conversely, Trump’s character-first attitude to politics has disadvantaged his attempts at coming across as sympathetic; no tragic arc or catharsis can save his story — or, for that matter, those subject to the very real consequences of his “unreal” presidency.

Ancient tragedy and comedy masks, Hadrian’s Villa | Source: Wikimedia Commons

It makes sense then, from this classical understanding, that it was the comedians who first took on the mantle of representing Trump, even though he quite comfortably inhabits a caricature of a tyrant. So how has our tyrant found his way into comedy? And furthermore, is representing Trump in the theatre a tragic task or a comedic one? Eustis’ production seems to signify a change in the overwhelmingly comedic tide of satire, and comedians are relying more and more on tragic notes to add poignancy to their bits. The two genres are halves of the same coin, after all, and ideally, the two would complement each other. Art, through its representation, has the power to instigate action, and the persuasive power of any piece of art lies in its ability to use both the relief of comedy and the gravitas of tragedy to create a convincing representation of reality. The comedic community has kept us laughing through a range of unbelievable incidents. Yet the theatre community, spearheaded by Eustis and his contemporaries, respond by asking: are we still laughing? Our tyrant has seemed to do the impossible multiple times, including existing as a tyrant in a decidedly comedic reality. But when does this comedy become a tragedy?

[…] Trump’s character-first attitude to politics has disadvantaged his attempts at coming across as sympathetic; no tragic arc or catharsis can save his story.

It’s simply not enough to apply the tried and true classical archetypes to figures like Trump. Such applications run the risk of falling into the type of trap that Eustis avoided when he assured the New York Times that “Julius Caesar is [still] Julius Caesar” — namely, the risk of arguing that Trump is just another tyrant figure, and not his own brand of autocracy, born of its own concoction of right-wing and exceptionalist thinking. It puts Trump in a familiar box when the trademark of Trump’s acting is his use of the unpredictability card, of going off script, as it were. The questions that the comedians are asking theatre directors is are we still laughing? Will there ever come a point where our gasps of surprise turn into gasps of horror, when our laughter will turn into fearful baring of teeth? Or have we already gotten to that point? The task of molding Trump into a tragic figure requires more than simply attaching him to the long lineage of Julius Caesars, or even feeding into the comedic parody. Furthermore, it stunts the range of possible creative responses to his actions. If one of the most essential responses to Trump’s administration is a call to creative arms, then we need to allow for any and all types of responses that might ignite a fire of political resistance. It’s all too tempting and perhaps fitting to depict Trump — a hyperbolic figure by nature — through the lens of a performative genre such as tragedy or comedy that relies on exaggeration and distortion. Yet, wouldn’t it be all the more powerful to depict him simply as he is? It seems to me that that is the harder work at hand — to demask the tyrant as he has projected himself onto debate stages, and to peer inside his psyche, or whatever other element marks him as human. That’s the true work of the playwright, at least in ancient terms: to paint psychological portraits of human beings in order to provide the audience with a reflection of society. As Eustis was quoted as saying in defense of the theatrical craft, “When we hold the mirror up to nature […] often what we reveal are disturbing, upsetting, provoking things. Thank God. That’s our job.” And so the question remains: are we still laughing?

Billboard advertising Public Theater’s 2017 production of Julius Caesar | Source: Public Theater/Instagram