JENNIFER FRIEDMANN

6:43 PM, February 1, 2016. I drop my phone on the concrete floor of the Des Moines field office bathroom and spiderwebs spread across the screen. The battery is at 8%, worn down from months of searching for reception between small towns in Kansas, and from a day of navigating between 150 doors in Oskaloosa.

The shattered screen lights up — my boss. Glass slivers in my finger as I swipe to answer. “Are you near your car? Yes? Good. I’m going to send you an address. I need you to pick up two people from there and bring them to their caucus site before 7:00 P.M. or they will not be able to get in.” I go 50 in a 30-mph zone the whole way across town to an apartment complex where two women are standing outside in the bitter dark. They are overflowing with gratitude, just coming from a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, where one of the women who’d been having a rough time had decided she wanted to start being part of institutions greater than herself and was reconsidering her apathy towards voting. She had decided that she wanted to go caucus that night for Hillary Clinton, whom she had always admired, because “she’s strong, like I want to be.”

I get them to the back of the line outside the primary school gym at 7:00 exactly and, on the verge of sobbing, with all the authority I can muster, tell the line volunteer that these women must be admitted to the caucus or else.

When NBC finally announces that we’ve won Iowa — all precincts reporting, by some fraction of a percentage — it is 2:00 A.M. I am lying on the floor of the field office surrounded by exhausted staffers and soda cans, legs rubbery from four days of knocking doors nonstop in the snow, full of a quiet, definitive pride.

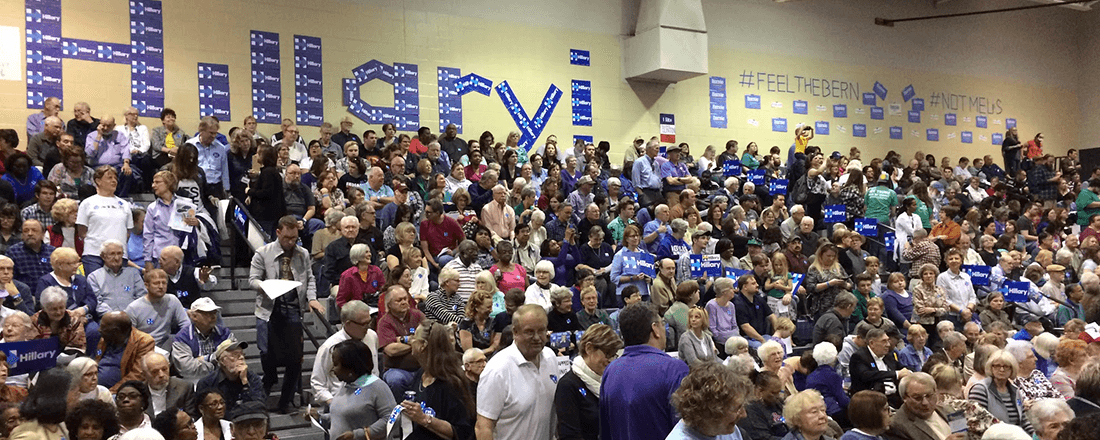

Hillary Clinton at a Des Moines, IA campaign event | Source: Gage Skidmore/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

The Kindness of Strangers

On my first day as an organizer in Kansas, I arrive at my boss’s house, where I will be staying until someone can find me housing. My “turf” spans 64 counties, two time zones, and one of the most conservative districts in the nation. I need to make 900 phone calls this week despite having only 600 “likely supporters” in my universe. “Call twice.” I also have to convince a few dozen people to drive over three hours to knock doors in Iowa, in the snow. I learn that, despite professing an Emersonian penchant for self-reliance, I am okay with asking total strangers for ridiculous things. By the end of the first week, I have secured not one but three guest bedrooms, a printer I can use, the Wi-Fi passwords to every cafe in Topeka, and a single phone bank volunteer who will keep coming every week except the one when he has heart surgery.

Courtesy of supporters in Kansas | Photo by the author

Campaigns are knit together by the kindness of strangers: HQ anticipates their gifts (“just get volunteers to donate that”); organizers use them to survive. The family who adopts me in West Des Moines asks me what type of snacks I like and buys every flavor of the granola bar I mention so I’ll be sure to have the one I like. Casseroles and baked beans show up in the Manhattan, KS field office so I won’t starve. The keycode to an Estes Park apartment is offered after the caucus when I need to get out of Kansas. A coffee gift card appears on my desk. Another adoptive family never complains when I wake up the dogs at midnight after a long night at the office. The homes and furniture we borrow, the lives that shift around our presence. Nothing is asked in return, except that we win.

Working 16 hours a day means that work ceases to be work — there are only waking hours and sleeping hours. It never occurs to me to not work during the waking hours. Every conversation, even over beers, revolves around Hillary and ends in a volunteer ask: “So which day this weekend will you come with me to knock doors — Saturday, or Sunday?” To most of Kansas, I am the Hillary girl. Any unique component of my identity is meant as a layer of approachability on top of blank passion. Women for Hillary. Hikers for Hillary. Chicago Public School alumni for Hillary. Warby Parker-wearing, hip-hop-loving, bird-watching, sci-fi nerds for Hillary. My last name is Hillary Rodham Clinton.

We went to Kansas because organizing is the way to inspire change from within the community, even if it takes many cycles.

The Stories We Tell

We learn to use our “personal story” at every opportunity, rehearsing different lengths for recruitment calls and county party meetings. It is far more persuasive, and more pleasant, than facts. If CHIP saved your life as an uninsured kid, you’ve got a reason to support Hillary that doesn’t require articulating how she’d revamp the public-assisted private-sector healthcare system. It also serves as a defense mechanism past the rapidly disintegrating boundary to my “real life.” Lots of white boys tell me that I am wrong; they use terms like “neo-con” that they’ve seen on Reddit, or they unwittingly parrot conservative talk show radio hosts and their 30-year effort to discredit this woman. I would like to recommend a pile of articles and books, discuss at length her history as an activist and accomplished public servant, and point out the particular policies and speeches that inspired me to quit my tech job in San Francisco and move back to the Midwest. Instead, I tell my personal story. I try not to lose friends.

Will and Daniel, the Nebraska organizers, keep me sane. When there is a naked doll face-down on a battered couch in the screened-in porch I’ve just let myself into, I text them a picture and tell them to come rescue me from the basement dungeon if they don’t hear from me. When my packet full of doors to knock is mostly residents of a retirement home with unfavorable entry policies, they offer advice: “Put your ninja skills you’ve been honing your whole life to the test. Ask to use the bathroom. Put your clipboard in a pizza box and pretend to be the delivery chick. Do your senior home entry hair flip: ‘I’m going be at the caucus Monday night, you should come too ;)’”

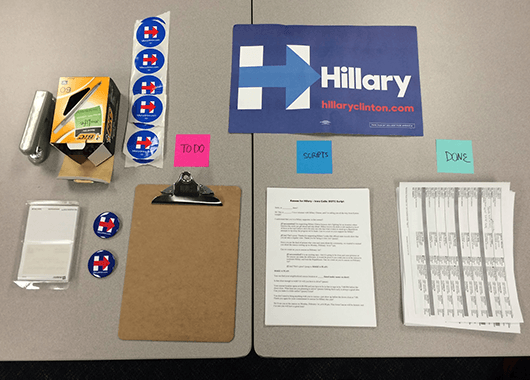

Phonebank setup | Photo by the author

We are joking, usually. We help each other push far beyond our comfort zones until rejection and safety are no longer concerns. We send Snapchats of terrifying dogs, inaccessible doors, Panera interiors, and piles and piles of data to enter alone on a Saturday night. We watch Billions over Google Hangout sometimes, if we finish before 11:00 P.M. We dream of a day when we will have our own army of interns pitted against each other in a bloody competition over who can make the most calls.

Interns are essential. We call them “fellows” and make sure their Twitters are scrubbed of anything some Fox News reporter might use to make us “look bad,” whatever that means. I drive a car-full of them up to Council Bluffs on the coldest recorded day in human history and deposit half, car-less, on a snowy suburban road, praying that they finish their packets before they freeze to death. In exchange, I tell them stories, teach them the volunteer team leadership model, and help them get selfies with Hillary and Bill. I never meet Hillary, because I am a staffer, and fangirling with the candidate is not going to get those doors knocked. Needing to be strong for the interns pushes me through the worst times, like those times during the six-hour marathon phone banks when I wonder how exactly my Ivy League education is relevant to the dialing of yet another 775 area code.

Nothing is asked in return, except that we win.

Four days before the KS Caucus, I learned that we will not be knocking doors in Salina. Not one. I have spent weeks driving four-hour round-trips on the I-70, cultivating volunteers, training leadership, and preparing them to knock doors for the caucus, estimating that we can win 7 of the 10 delegates — believing it. My team is ready, bright-eyed, scheduled weeks and weeks in advance for these last few days, risking small-town reputations to display Hillary placards in their windows. I cannot tell them that Hillary has decided they do not matter.

A surreptitious box of targeted doors is delivered to the front porch of my volunteer canvass captain. I know she’ll do what I’ve trained her to do, because this is what it is to be part of something greater than ourselves.

I never meet Hillary, because I am a staffer, and fangirling with the candidate is not going to get those doors knocked.

It is not until we lose the KS caucus 68% to 32% that I realize I, too, had not been told. This is what is required of field staff: they must never be allowed to lose hope, to conceive of any possibility other than victory. In the rurals, that requires an ignorant optimism, an anti-logic that permits the confirmation bias of talking mostly to supporters to shield you from reality, even when that reality yells at you about Benghazi in the campus coffee shop and calls you a baby-killer.

In a well-functioning field program, the organizer denies this reality by feeding on the stories of her volunteers, and her volunteers feed on the passion of the organizer in a feedback loop of devotion.

There is the 80-year-old daughter of Mexican railroad workers who co-founded the local chapter of NOW, receiving donations quietly from women who told her that they couldn’t publicly support the organization because their husbands would never let them; she couldn’t believe she would live to see the first woman elected as President.

There’s the college student from the staunchly Republican family who evaluated each candidate thoroughly, and found that Hillary’s platform would do the most for people with severe special needs, like her sister.

There’s the Vietnam Vet who is staunchly anti-gun.

And, of course, there’s Nathan, who shows up to the basement of the Kansas City church every day after he gets off of his second shift at McDonald’s and starts knocking doors in the neighborhoods where the white volunteers won’t go.

People whose lives depend on Obamacare, people without documentation, people who have close to nothing but give it all anyway.

Close to the end, we share their stories with each other on our nightly calls, reminding each other who we are fighting for, why it was so important that we win.

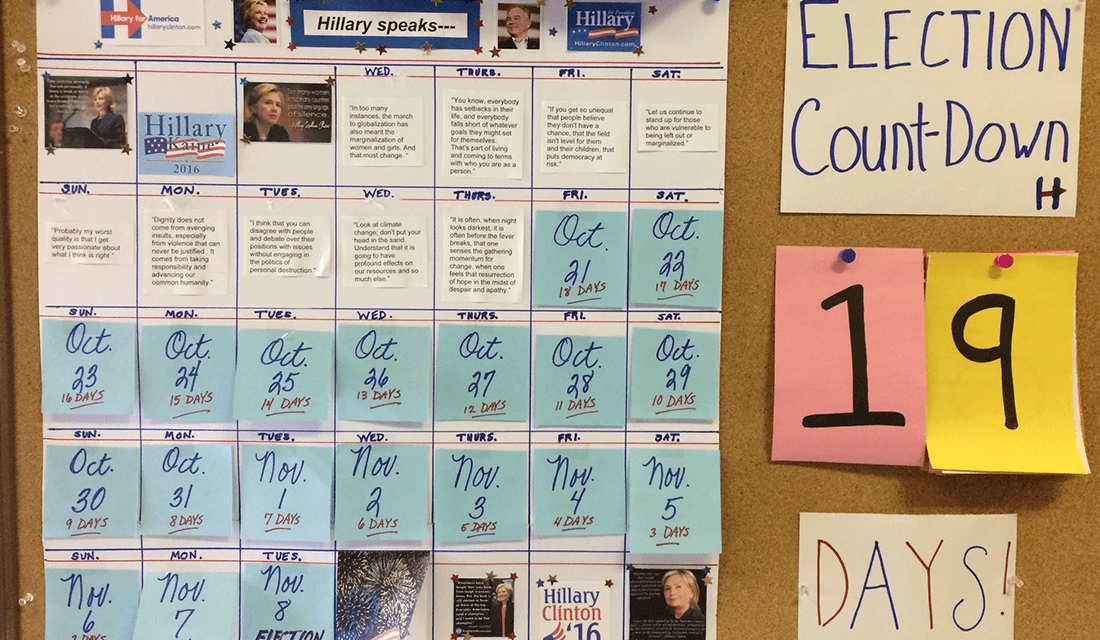

Manhattan, KS Caucus | Photo by the author

Many months later, I understand that we were never going to win in Kansas. We went there because Hillary wanted to, because she hired organizers in all fifty states, even if there was no chance of sweeping the state in the general election. We went to Kansas because organizing is the way to inspire change from within the community, even if it takes many cycles. My volunteers knocked doors for many local Democratic races in November 2016. They even won some. Now they’re running for office themselves. That was why.

Whatever It Takes

I use the savings from my tech job to buy a Subaru with heated seats and the window wipers that still work in the middle of Kansas ice storms. I name her Inka — after one of the Russian space dogs — and use her to achieve extreme things. 6,000 miles in the first month; 35,000 miles in eight months. Brooklyn [the national campaign headquarters] doesn’t know what to do with us after we sweep the Super Tuesday primaries, so I drive around the country in what I hope is the right direction, spelunking in Mammoth Cave and backpacking solo for a few days in the Great Smoky Mountains. I am wrong; they tell me I will be doing opposition research in California and that I need to be there by Friday. Inka and I and go for eighteen hours in one day, from eastern Arizona to Flagstaff, AZ, while I blast vapid young adult superhero audiobooks to stay awake.

I spend hours in cold municipal buildings photocopying legal documents proving definitively that Trump is the worst human ever, and between courtrooms, I get to traverse this glorious country and its most eccentric roadside attractions. During a very lonely but beautiful week in Aspen, CO, I acquire expertise with microfilm machines and the intricacies of property law. There are new types of conservatives out west, ones who want land rights back, ones who don’t care about abortion, and ones who really like both guns and the environment. I develop strong opinions about which interstates are the best, and for the first time in my life, the presence of Starbucks thrills me, because it is not gas station coffee. I don’t tell anyone I work for Hillary and I feel like a secret agent.

We learn to use our “personal story” at every opportunity, rehearsing different lengths for recruitment calls and county party meetings. It is far more persuasive, and more pleasant, than facts.

A few months and a few thousand miles later, I’ve collected the requisite proof of scrappy determination to graduate to a Regional Director level, for which I will manage a collection of rural organizers via “When I was in Kansas…” stories, one for every occasion. For the general election, I moved to the gorgeous, rolling hills of Southeastern Ohio, where I learned that I’ve been saying “Appalachia” the city way. I hire an amazing team who sacrifice pant legs to German Shepherds and early mornings to county parades to activate every single Democratic voter in the region. Sometimes their stories break my heart: when a black volunteer had the cops called on him; or when we learn the extent to which a community has been transformed by opioid addiction; or when an organizer had to leave their supporter housing, because the family’s daughter has given birth to a baby she didn’t know she was carrying. Other stories, we cherish; I come to love this fiercely independent land in the hills. When a phone bank leader has a Hillary yard sign that keeps getting vandalized, she promises to vaseline the stakes and cover them with crushed light bulbs. She is, perhaps, more polite than the Ironton man with the gigantic beard, who happily recounts, “I took out my shotgun and told those punks to leave my yard signs alone!”

Between our highs and lows, which we share every night together on the checkout call, I am the center of the wheel, responsible for keeping the spokes connected while we push ever forward, with more and more intensity, doing whatever it takes to keep moving. Now I am the one who fills the gaps in logic for why my team needs to register so many voters in 90% Republican towns, referring to the “statewide win number,” the number of voters registered and doors and phone calls we must have completed by November 8, or else Trump becomes our president. We learn to trust the numbers above all else. We exceed them, and thus there is no way we can lose.

Photo by the author

At 2:00 A.M. on November 9, I am sitting on the cement outside the field office next to someone’s smashed beer bottle, singing Ella Fitzgerald’s “Misty” to myself. My team is inside, champagne sitting unopened, forgotten, in the mini fridge. We have turned off CNN at this point. I recognize, with some solace, that all former and future sadness in my life cannot compare to this.

Some of the white boys call me. I seem to be regaining friends, or dissolving my identity, already.

Will calls from Pennsylvania. For once, we have very little to say to each other.

“Thousands and thousands of people will die,” he mumbles.

“I know.”

“I worked harder than humanly possible.”

“Me too.”

“If you’d known we’d fail back in January 2015, would you have done it?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah. Me too.”