ANGELINA CHAIRIL

About Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi

Sandro Botticelli | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Widely known as Sandro Botticelli, the story of the Florentine master turned present day global pop icon is indeed a fascinating one. Under the patronage of the famed Medici family he rose to prominence in the late 15th-century Italian art scene. Son of a humble goldsmith, young Botticelli flourished as a painter under the apprenticeship of Florentine painter Fra Filippo Lippi. His reputation as an established painter in Florence at the time is further acknowledged as he started his own painting workshop in 1470, as well as a 1480 commission of the Old and New Testament frescoes in the Sistine chapel by Pope Sixtus IV. His most well-known masterpieces were created during that similar period of time, with La Primavera painted in 1482 and The Birth of Venus in 1484.

This fame and acknowledgment, however, is short-lived during his lifetime, possibly due to a mention in the authoritative Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, a 1550 book by Giorgio Vasari. Having seen both La Primavera and The Birth of Venus at one of the Medici properties, Vasari recounts his observations of Botticelli’s works as showing admirable skills in drawing, coloring, and composition, noting that his works are of tremendous beauty. This artistic valuation and praise, however, comes second in the hierarchy of the High Renaissance art as Vasari valued the works of Michelangelo and Raphael as “perfection” — a statement which eclipsed Botticelli’s admirable status in the High Renaissance period. Despite this, Botticelli was dimly remembered during this period for his celebrated illustrations of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

Three hundred years on, his works and influence rose from the grave, as it was rediscovered and became the adoration of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of the 19th-century; an adoration which lingers on to the present day. The story of this decline, rediscovery, and revival was recently visually re-enacted through the Victoria and Albert Museum’s spring blockbuster exhibition, “Botticelli Reimagined” — a visual celebration of Botticelli’s works as well as his ongoing influence in present day fine arts and popular culture. This exhibition includes around 150 works, 50 of which are original creations of Botticelli.

Botticelli Reimagined | Source: © Victoria and Albert Museum

Exhibitions as a Static Performance

Most important of all, every performance — be it live or static — “manipulates” environments prepared specifically for an audience so as to achieve a certain goal.

Note the use of the word “re-enact” to describe this exhibition, as it will set the linguistic tone for paragraphs to come. Though arranged in a reversed manner, the chronological nature of the exhibition’s display suggests a great intent of identifying “Botticelli Reimagined” as a focus in narrative, rather than a mere visual account of Botticelli’s artworks. This somewhat overpowering presence of a narrative thus encourages the audience to look at the exhibition in a performative manner.

Just as Botticelli’s life story takes an unexpected twist, to speak visual art through the language of performance could very well be a twist worth attempting.

Similar to a live performance, an exhibition includes more or less comparable elements: a design of display is like that of a set design, curation is similar to direction, different sections make up the different scenes or acts in a narrative, and artworks are the stars of the show. Most important of all, every performance — be it live or static — “manipulates” environments prepared specifically for an audience so as to achieve a certain goal. Keeping in mind an indisputably crucial role of the audience in a performance, how does “Botticelli Reimagined” live up to the suspense of these audiences?

On Beauty and Its Reinterpretation

Entering the gallery room, the first encounter with the exhibition is a short clip from the first James Bond movie, Dr. No. The scene played, in particular, was of Bond girl Ursula Andress emerging from the sea in a white bikini, clutching a conch shell — portraying a modern 20th-century revival of the Birth of Venus. This scene, and the whole gallery room, is additionally drowned beneath a melody of Bob Dylan’s Sad-Eyed Lady of Lowlands, with a nearby accompanying wall text suggesting the relation between the singer’s ballad and how it references the artist’s melancholic female types.

Botticelli Reimagined | Source: © Victoria and Albert Museum

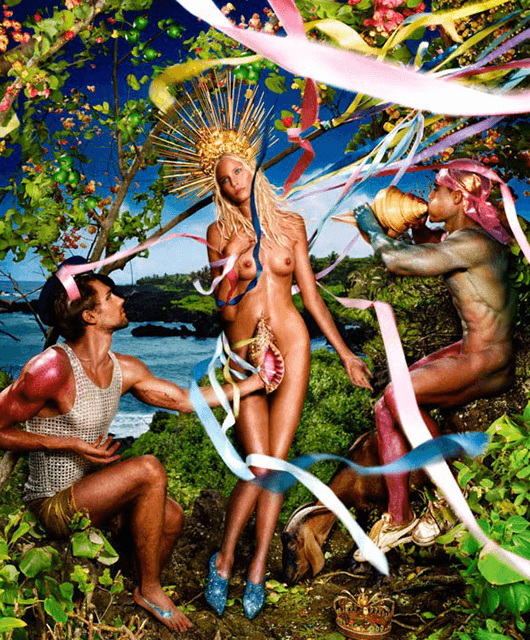

David La Chapelle’s Rebirth of Venus | Source: © Victoria and Albert Museum

In this first section of the exhibition entitled Global, Modern, Contemporary, the audience will also find a wide array of Venus-inspired paraphernalia altogether screaming the same language of kitsch. A silkscreen close-up of Venus by the pop-God Andy Warhol, a genital like gold conch shell strategically placed to cover a shiny nude woman’s private parts in a photographic tableau by David La Chapelle, and a rendition of Venus boasting oriental facial features as painted by Yin Xin along with two outfits by Dolce & Gabbana — with fragments from The Birth of Venus printed all over them — these works, while presenting a contemporary point of entry to the story of Botticelli, are at the same time blatantly confusing for the audience who came armed with a thirst to learn the story of the great Florentine artist.

It seems as though in attempts to tell the story of Botticelli’s glorious afterlife, the directors of the show undertook a clichéd method of attention grabbing.

They chose a star-studded cast to perform a simultaneous impersonation of the artist’s most notable character (surprise, surprise!), Venus. It almost feels like an attempt to address the history of American musical theatre by showing a medley of popular Broadway hit songs — it’s catchy, but it doesn’t tell you anything about the history of American musical theatre.

On a Positive Note: Birth of the Neo-Critic?

With regards to visual art, the inherent instability of visual language gives rise to multiple meanings and interpretation, and the audience is thus free to interpret a text or image regardless of authorial intention.

This method could be seen as looking at the past through the eyes of the present; a thoughtful way of inviting the audience to dip their toes in the water, so as not to be overwhelmed by the distant discourses of 15th-century Renaissance art. Considering that the artist’s most visually familiar works (La Primavera and The Birth of Venus) are not physically present, to those less familiar with Botticelli’s career the first act of “Botticelli Reimagined” is a slap in the face to remind each visitor just how monumentally influential Botticelli’s images are in the present day; to make sure they keep in mind which 15th-century Renaissance artist is the star of the show.

Botticelli’s La Primavera and Birth of Venus | Source: Wikimedia Commons

In finding another way to make sense of this loosely interpreted legacy of Botticelli as presented in “Botticelli Reimagined” one may also confide in a possible proposition such that discussed in the short essay “The Death of The Author” by Roland Barthes. In it, Barthes suggests that most often texts can only be understood in relation to other texts, and it is rare that they only convey a single meaning. With regards to visual art, the inherent instability of visual language gives rise to multiple meanings and interpretation, and the audience is thus free to interpret a text or image regardless of authorial intention. The audience reception itself is, therefore, relevant in the projected narrative of a story.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (photo taken by none other than Charles Dodgson, a.k.a. Lewis Carroll) | Source: Wikimedia Commons

In any case of understanding a text, play, or, in this case, an artist’s legacy, according to Barthes, the author should no longer be considered a divine source and authority of how the work is interpreted. In defense of the show’s curators, the way they framed the essence of Botticelli’s legacy has hence become a parallel narrative in the discourse of Botticelli’s story, just like how the Pre-Raphaelite artists of the 19th-century started their own parallel narrative in looking at Botticelli.

This determines how the audience’s interpretation of this reinterpretation of a life story is shaped, though to continue the canon in this fashion will eventually lead to even less and less of Botticelli and more of what many may think of him primarily — as the creator of a classical standard of beauty. After all, to quote Barthes again in this matter, “The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author;” unveiling a shift of command to the new generation of critics and interpreters camouflaged within the audience.

One Century Prior, a Frame Narrative

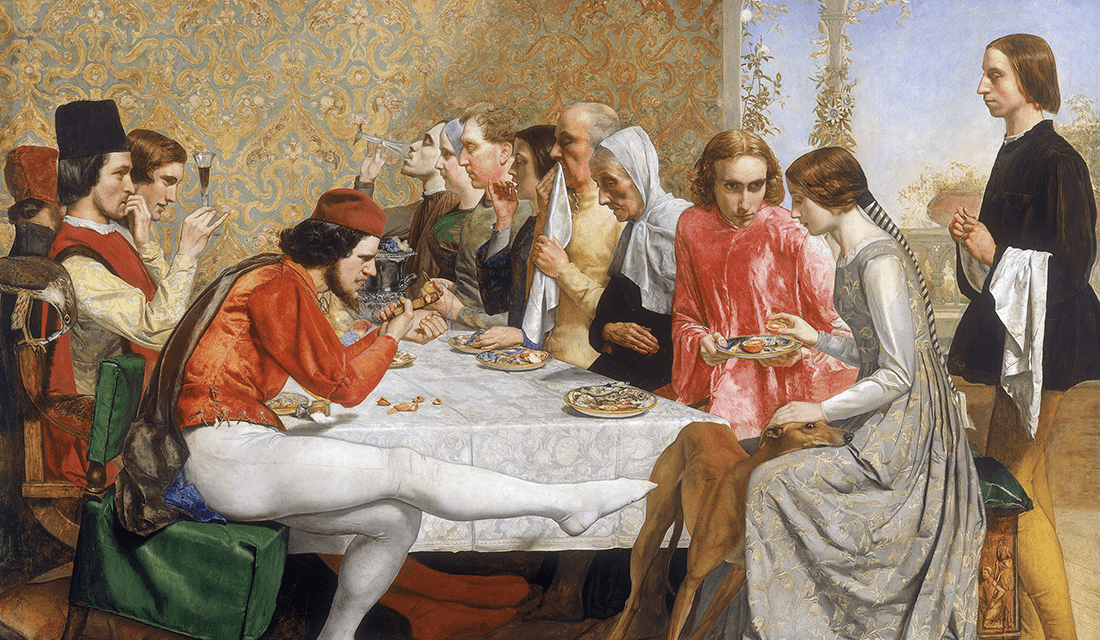

Still narrating a story from Botticelli’s afterlife, this second act is played by a whole new set of different actors; a series of creations by the Pre-Raphaelite artists who rediscovered Renaissance romanticism and idyllic beauty from the works of Botticelli. This rediscovery is thought to have been sparked by the Napoleonic secularization of religious houses, resulting in the dispersal of this “primitive” High Renaissance art in London and Berlin. In 1848, the first Italian panel by Lorenzo Monaco entered the National Gallery in London — an artwork believed to be the influence behind Sir John Everett Millais’ inaugural Pre-Raphaelite creation, Isabella.

John Everett Millais’ Isabella | Source: Wikimedia Commons

The story of “Botticelli Reimagined” thus continues with its second act: a gallery entitled Rediscovery. In a typical narrative arc, this would be the section of the plot marked as a “twist.” Continuing a visual journey through the curated legacy of Botticelli, the narrative is set one century prior to Global, Modern, Contemporary. Though one could only imagine how visually nauseating this century-long time travel is to the audience, a somewhat comforting view of warm-colored set display consisting of softly colored carpet and wall combination comes as a relief to the eyesight after the shining black set and glittering work combo of the previous gallery. Visually disjointed, but comforting nonetheless.

Botticelli Reimagined | Source: © Victoria and Albert Museum

The audience is faced with another set of Botticelli appropriations in a slightly more uniformed stylistic method, such as Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s flame-haired beauty in the striking 1873 La Ghirlandata and a tapestry by William Morris titled The Orchard, clearly mimicking the composition of La Primavera as well as highlighting the beginning of Botticelli’s influence in decorative art.

As a soundtrack of Claude Debussy’s 1887 musical suite Printemps (which was inspired by a reproduction of La Primavera, by the way) plays in the background, one thing is made clear in this section: that the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood found a gem in Botticelli’s works; an essence worthy of adoption and reproduction in their own plays — an apparent, more identified frame story within the main narrative such that one of Dante Gabriel Rosetti.

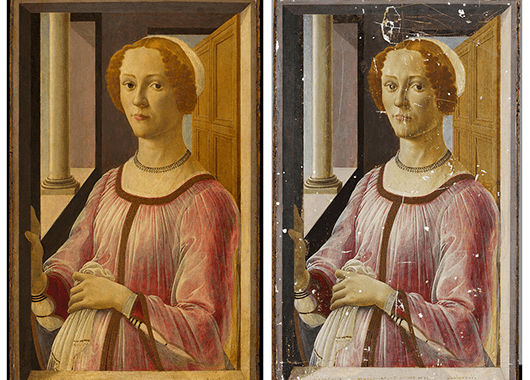

Portrait of a Lady, Known as Smeralda Bandinelli (after and before restoration) | Source: © Victoria and Albert Museum

The man credited with discovering beauty in the then-unconventional depictions of Botticelli’s works might not have expected this unlikely revival of interest in Botticelli when he purchased his Portrait of a Lady, Known as Smeralda Bandinelli for a bargain of £20 at Christie’s auction house in 1867; proving just how undervalued Botticelli’s works are at the time. This portrait, which finally made it to the V&A’s own collection — included in this exhibition and hung nicely in the next room — was then re-sold by Rosetti for £320, as he sold his own creation to the same patron for £735.

Though Rosetti himself has never stepped foot in Italy, his study of Botticelli’s work ignited a Renaissance fever among his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries, followed by their travels to Florence in search of this hidden gem of unconventional beauty.

FaceTiming Botticelli

Having travelled across a centuries-long journey through a kitchen-sink type display of Botticelli’s afterlife, in the most anticipated final act of “Botticelli Reimagined” the audience finally met the esteemed painter face to face, as they are confronted by the original casts of the show on stage. To much of everyone’s delight, the good looking cast performed really well in this final act, entitled Botticelli in His Own Time.

Botticelli Reimagined | Source: © Victoria and Albert Museum

Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Among the list include original works by Botticelli himself pulled from the V&A’s own archive — a selection of brown ink on vellum illustrations of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, and the aforementioned recently restored Portrait of a Lady, Known as Smeralda Bardinelli. Moreover, there is a great selection of his religious-themed works, namely the stunning Madonna and Child and Two Angels from Vienna and the larger than life (and unmissable) Mystic Nativity — the only known signed work by the Maestro created towards the latter end of his career — on loan from the National Gallery.

Adding to the diverse portfolio of this Florentine artist are two prototypes of the Venus figure, each an equally stunning standalone image that lets the audience marvel in great detail at the undisputed universal standard of classical beauty. Dated 1490, the pair is on loan from the collection of national museums in Berlin, of which its Gemäldegalerie venue hosts the same exhibition franchise, “The Botticelli Renaissance,” last year.

In addition, a series of Botticelli’s beauty portraits — supposedly all modeled by his long time muse Simonetta Vespucci, in a variety of possible views of the woman’s face and hair — are also present. Connoisseurs of beauty and aesthetic would undoubtedly feel spoiled rotten by such a generous ‘FaceTime’ of this calibre.

A Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Speaking of FaceTime, we should point out the fact that it is a tool of great relevance within the discourse of cultural analysis — both in performing and visual arts. Arguably, as mentioned in Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the essence, or in his term “aura,” of an artwork lies in its unique presence in a specific time and place. He argues even further to state that this aura is one which is impossible to reproduce through other means.

In the context of “Botticelli Reimagined,” what can the audience gain from being in its physical presence?

A rare combination of Botticelli’s masterpieces from the world’s esteemed art institutions, that’s one. The unique experience of being face-to-face with these works gives a sense of historical otherness in relation to us, sparked by the immediate feel of distance between the observer and the observed — one which is unlikely in a non-direct or physical encounter. Being in the physical presence of this exhibition also means the audience can feel the pulse of Botticelli’s aura grow stronger as they journey from the first to the last gallery.

Also, fortunately, the static nature of an art exhibition allows for several unique ways one could enjoy the story. Though it might be frowned upon, we could easily fast forward to the end and, arguably, to the best part of the show — really immersing oneself in the rich legacy of Botticelli and his studio. Unlike that of watching a live performance, the audience’s encounter with the narrative is not controlled; they could pause and ponder on a certain artwork that is of personal interest to them; they could rewind, pick, and choose certain artworks to make up a frame narrative of their own. Best of all, in this particular scenario of encounter, the audience gets to play director.