KATIE BELLAMY MITCHELL

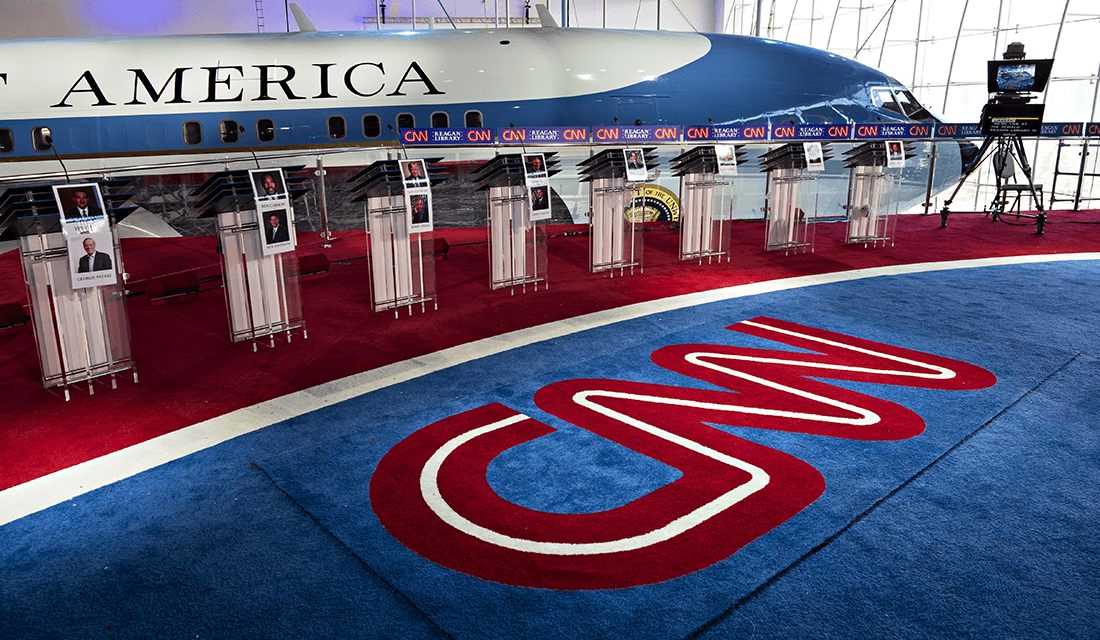

A stage can be as simple as a stretch of concrete sidewalk, or as elaborate as the red- white- and blue-carpeted end stage CNN built for the second Republican presidential debate. A small and select audience is seated in chairs on the same level as the then-eleven presidential candidates, who stood at podiums in front of President Reagan’s retired Air Force One — a symbol of the Republican Party, framing those who hope to decide that party’s future. One less obvious detail of the stage’s construction is particularly pregnant: in order to reach the height of the plane, CNN had to elevate the entire stage above three stories of metal scaffolding. CNN placed the stage both politically and physically out of reach of the American audience. Despite invoking the vocabulary of democratic spaces, the debates, rallies and town hall meetings that comprise the 2015-2016 US presidential campaigns are far from democratic.

CNN 2016 GOP Presidential Debate Stage in California | Source: © CNN/WhoTV.com

The act of building a stage categorizes the crowd at an event in terms of their participation, and therefore enables political interaction. Located on-stage, political performers are separated from their attentive audience. The nature of this separation establishes both who the participants are, and the terms of the relationship between these participants: politicians and their constituents. The architectural evolutions of stages — from Greek amphitheatre to church to opera house to boxing ring — reflect changes in this relationship. How many people are supposed to see the performance, and from where? Who should be in the audience? How much of the performance is supposed to be visible? And how much should the audience be able to interact?

Despite invoking the vocabulary of democratic spaces, the debates, rallies and town hall meetings that comprise the 2015-2016 US presidential campaigns are far from democratic.

In a democracy, politicians are representative of, and ultimately responsible to, voters. If voters are not allowed to participate, to ask questions, or to challenge and change the content of their representation, then the democratic process has failed. Because of this, audience participation is uniquely necessary to the performance of democratic politics, even more so during a political campaign to determine who will occupy a long-term speaking position.

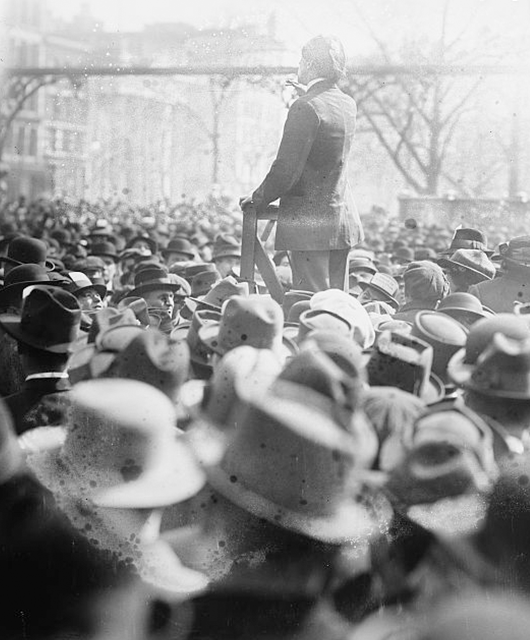

Source: Library of Congress/Flickr

In the ideal democracy, a citizen stands above the crowd for a moment, speaks while others listen, and then sits down again to join the crowd. Then another person stands. The principle of such conversations applies to soap boxes, balconies, podiums, and all democratic stages: for the duration of the individual’s physical elevation, they are politically visible. The speaker is an authority, and this authority rests on the power of the crowd, who decides to listen or not. These political platforms are spaces that anyone can stand up on and speak from, if we choose to listen. Even the President must eventually cede the four-year-long bully pulpit we afford them.

On a soapbox, the audience directly determines the authority of the speaker. This small-scale elevation is a pure type of democratic and dynamic power differential, which facilitates listening on the part of both the audience and the speaker. The positions are interchangeable: each participant speaks and listens. When we build infrastructure around this relationship, we make the inequality more static. We do this for good reasons: in a town hall with a moderator or a debate, for example, we have democratically decided as an audience that the people on stage are the ones who should speak. We have decided that they are worth listening to. This staging still preserves a democratic check because representatives have to respond directly to the audience, often in a question and answer session. Once we add billions of dollars in campaign finances, the interests of mass media corporations, and a national audience, the relationship of accountability is unrecognizable.

The panel of moderators present in the debates during this election season — chosen by the corporation hosting the event, and supposedly representing the audience — physically removes the American audience from the political process. Now, only the moderators and select audience members with pre-approved questions can check or respond to the candidate on stage.

The refrain of “work within the system” only makes sense if the system works: if the performer acknowledges dissent, disruption, and responds to questions.

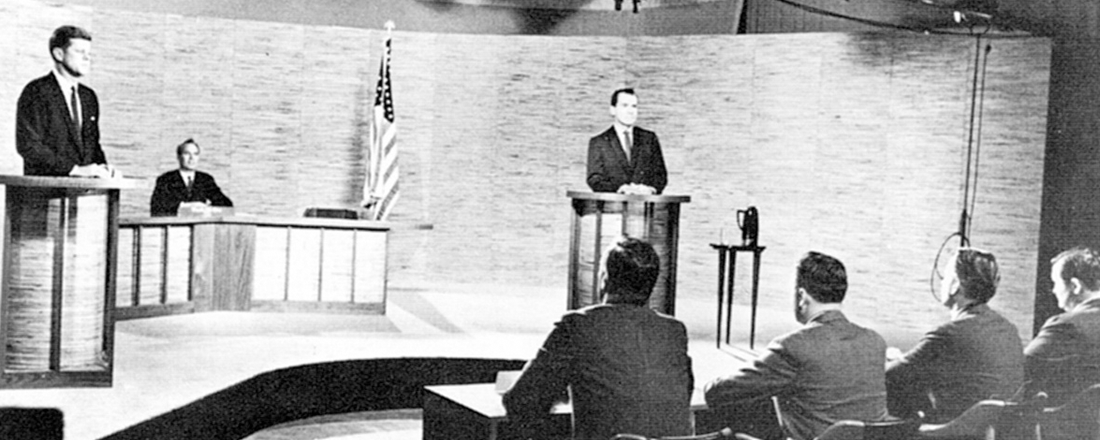

John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon during one of their presidential debates in 1960 | Source: UPI/Wikimedia Commons

Since the first televised presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960, the idea of candidate as performer, and politics as performance, has been increasingly relevant. We judge the competency of our leaders by how successfully they act out their role, by how well they can navigate their performance without getting thrown by a question, without stopping and ‘forgetting a line’ or betraying their character by contradicting themselves. When they fail, their legitimacy as a speaker crumbles. We want them off the stage. They don’t get elected. Someone else steps up from the wings.

In response to this highly controlled and unequal performance, we have a new type of audience. The protestor refuses to respect the political architecture of the modern “democratic” event. Protests happen in the context of a democratic process gone wrong. The refrain of “work within the system” only makes sense if the system works: if the performer acknowledges dissent, disruption, and responds to questions. It works if the stage is accessible to others, if the audience is also allowed its turn to speak. Protests happen when this inequality stratifies, when no one else is allowed to engage the performance. Protestors use the language of the political performance to point to the audience’s lack of a voice: holding signs, standing up, and speaking with authority.

What is offensive is a member of the audience refusing to relate to the stage in the ‘correct’ way, which is, apparently, to not engage the stage at all.

Across campaigns, candidates have ignored incursions on their performances. At a private event in South Carolina, #BlackLivesMatter protestor Ashley Williams asked Hilary Clinton a question about her support of mass incarceration, invoking the now infamous 1996 quotation that refers to at-risk black youths as super-predators: “We have to bring them to heel.”

Hillary Rodham Clinton | Source: Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

“I’m happy to address it,” said Clinton, “but you’re the first person to ask me,” she continued as the protestor was forcibly removed from the room. When the protestor and the offending sign were being dragged backstage, Clinton smiled: “Now let’s get back to the issues.”

Possibly more unnerving are the disembodied voices of the audience also caught on tape, attempting to silence the protestor. Variations of “You’re being rude,” “This is not appropriate,” and “You’re trespassing” cut across both Clinton’s and Williams’ voices, underscoring the architectural fragility of the performance of democracy and its inability to actually engage a dissenting voice, or an unplanned question.

Williams’ physical removal from the political space — being dragged off stage to applause — is particularly ominous when considered alongside Donald Trump’s campaign, which has done much more to actualize the threat of violence against dissenting voices. It is darkly ironic that Trump invokes his right to free speech while defending his right to hold a rally, as he explicitly threatens violence against protestors exercising their right to speak. He asked his selected audience in Las Vegas: “Do you know what they used to do to [protestors] in a place like this? They’d be carried out on a stretcher, folks.” Rather than engaging voices from the audience, he removes them from the political space entirely, and threatens those who might speak with physical harm.

The logic of the disruptive protest functions on the ideals of democratic participation: the privilege of a representative speaking position is contingent upon the assent of the audience represented.

Donald J. Trump | Source: Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

In a conversation with Don Lemon on CNN, Trump defended his campaign against accusations of threatened and actual violence. Trump asserted that protestors, rather than his supporters, were the instigators. Rather than mentioning specific violent actions on the part of protestors, however, he focuses on what is most offensive: their entrance into the political dialogue, their voice. “We had one [protestor],” Trump said, “his voice was like Pavarotti, Luciano Pavarotti.” Though he goes on to describe the protestor as a ‘tough guy,’ it is striking that what first offends Trump is the quality of the man’s voice: resonant, beautiful, compelling. This is a voice that others might listen to — one that is worth listening to. What is threatening is how the protestor’s performance points to the inherent inequality of the political theatrical space today. What is offensive is a member of the audience refusing to relate to the stage in the ‘correct’ way, which is, apparently, to not engage the stage at all.

The logic of the disruptive protest functions on the ideals of democratic participation: the privilege of a representative speaking position is contingent upon the assent of the audience represented. Protestor Marissa Johnson invoked these ideals when explaining her decision to ‘shut down’ a Bernie Sanders Rally in Seattle and change the topic of the political discussion. She cited Sanders’s failure to provide — at the time of the rally — a comprehensive criminal justice reform package, after he was first confronted by Black Lives Matter activists at the Netroots Nation Town Hall on Saturday, July 18th, 2015. “Bernie Sanders had the opportunity to do that and did not,” Sanders said in an interview immediately following the protest, “because among other things I wanted to talk about the issue of black lives, of the fact that the American people are tired of seeing unarmed African-Americans shot and killed.” His lament seems odd considering the protestors addressed exactly those issues: the conversation happened, led by the American people he wanted to speak for.

In America today, when campaigns are as heavily financed and politicians often fail to represent those they speak for, there are fewer and fewer disruptions of the performance space. We, the audience, cannot stand up. The performance is impermeable, a monologue. The defense of this monologue through scripts, selected questions, security, and the threat of violence against those who would interrupt, has rendered political campaigning a performance of democracy rather than a democratic performance. The audience cannot stand up.