DANNY RIVERA

Are you a fan of Star Wars? Are you a fan of The Lord of the Rings? Are you a fan of Harry Potter? Star Trek? Game of Thrones? If you are, I don’t necessarily have to explain to you why you’re a fan. For the uninitiated, however — for those who have certainly heard of these franchises but may not necessarily have gotten into them and their various media — it may be hard to understand how they inspire such furor. Many things do — the idea of being a fan of something is hardly something new — but fiction, fiction that spreads over books, TV, movies, merchandising, fiction that inspires near-rabid excitement, has to have something beyond just being a really good book, TV show, or movie, right?

It does. A film can move you, touch you, thrill you, excite you, and still not incite the kind of fervor that The Lord of the Rings, Star Trek, and Star Wars have for 60, 50, and 40 years, respectively. No, what lies at the heart of these obsessions are the worlds in which these stories take place. Battles of good versus evil, stories of self-discovery, triumphs of friendship are all well and good, but they’re that much better when they take place in a fascinating world. I don’t mean just setting — I mean in an entirely different world.

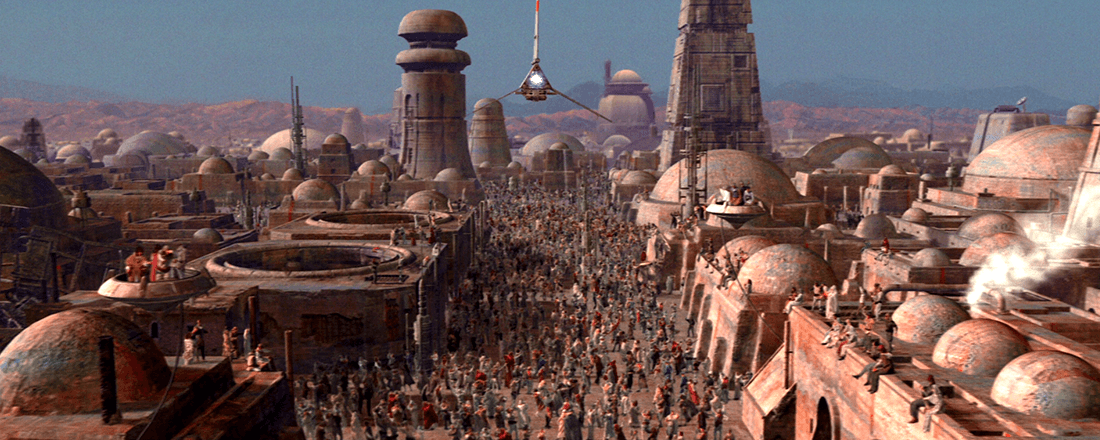

The Tatooine port-city of Mos Eisley, from Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope | Source: © Star Wars Wikia

These worlds, the best ones, that is, are essentially built from the ground up.

Christmas scenes from the Harry Potter movies | Source: © Harry Potter Wikia

One of the most exciting things about the Harry Potter series is that Harry’s adventures take place, essentially, right under our noses. He goes shopping for school supplies in a neighborhood hidden by magic right in the heart of London. It’s the thrill of escapist fantasy writ large: something wholly new and different right at our fingertips. Harry lives the very fantasy we get swept up in when we read or watch our favorite books, movies, and shows. He gets to walk through and touch and smell and breathe and taste and live in fantastical, magical places. These worlds, the best ones, that is, are essentially built from the ground up. New planets, new cities, new towns, new animals, new races, new languages.

Extensive research and time and effort was put into designing things that had even only a second of screen time — all in the efforts of building a landscape that looked and felt as if people had been living there for a long time.

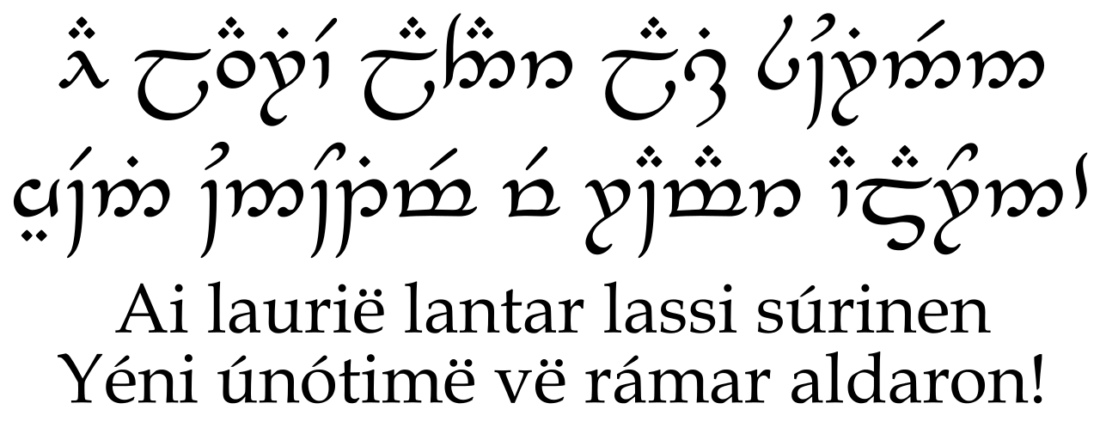

A new language is one of the most effective tools (if not the most effective tool) in building a fictional world. Language, I think, is the easiest way to communicate to an audience the reality and depth of a world you’re creating. Hearing a new language can be jarring, of course, but when it’s presented to an audience organically, it’s wholly immersive. After all, communicating is something we take for granted nowadays, isn’t it? How effective for an audience member, then, to see people communicating in a language easily recognizable as no known human tongue, but to see it done with the same ease and casualness with which we speak to one another?

Creating a language is by no means easy, but if you can present one to your audience, you’ve taken a massive step towards opening up the world. This presents various challenges depending on the medium, of course. The cast of the film and television adaptations of The Lord of the Rings and A Song of Ice and Fire famously had to learn Elvish as well as Dothraki and High Valyrian, respectively, before and during filming. The challenge there, of course, is not only making it sound authentic but being willing to reconcile (or fail to reconcile) what one reads and hears in their head with what is ultimately captured in performance. That is, however, a risk for all adaptation.

The Elvish language of Quenya, invented by J.R.R. Tolkien for his The Lord of the Rings series | Source: Wikimedia Commons

The work put into devising the languages for The Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones (the television show based on A Song of Ice and Fire), and even Star Trek is as well-documented as it is extensive, which leads one to ask, “Why?” Why spend so much time developing something that will play not an insignificant role in your work but won’t also be the main focus?

Simple: world-building. One of the driving philosophies behind the production of Star Wars was that the world had to feel real. It had to feel lived in. So extensive research and time and effort was put into designing things that had even only a second of screen time — all in the efforts of building a landscape that looked and felt as if people had been living there for a long time. What greater demonstration of civilization than language?

It’s a question of narrative distance and, I believe, world building. What is the language the audience speaks and understands?

Beyond the immersion, however, language is the very embodiment of the appeal of fantasy and science fiction: it is at once foreign and inviting. We consume fiction of this type to not only escape our world, but to enter another. I, personally, am terrified by the idea of going to a new place — not knowing the language, the culture, even the lay of the land — and having to find my way. I can imagine, however, that the thrill I get entering a new fictional world is the same kind that compulsive travelers get. Nothing is more alienating than being unable to understand someone speaking to you, but when that comes in the context of, well, adventure, it’s almost a dare to try to understand.

Concept art for the award-winning opening title sequence of Game of Thrones | Source: © Art of the Title

It would be near-impossible to learn about, let alone navigate these new worlds, without help, which is what these fictional stories often provide. In Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, we meet Han Solo, a swaggering, well-traveled smuggler who understands a variety of different languages. Luke Skywalker is, in essence, the audience’s avatar, wide-eyed and excited, and Han (and to an extent, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Luke’s mentor and neighbor) guides Luke through this new world, translating languages and helping him navigate cultural pitfalls.

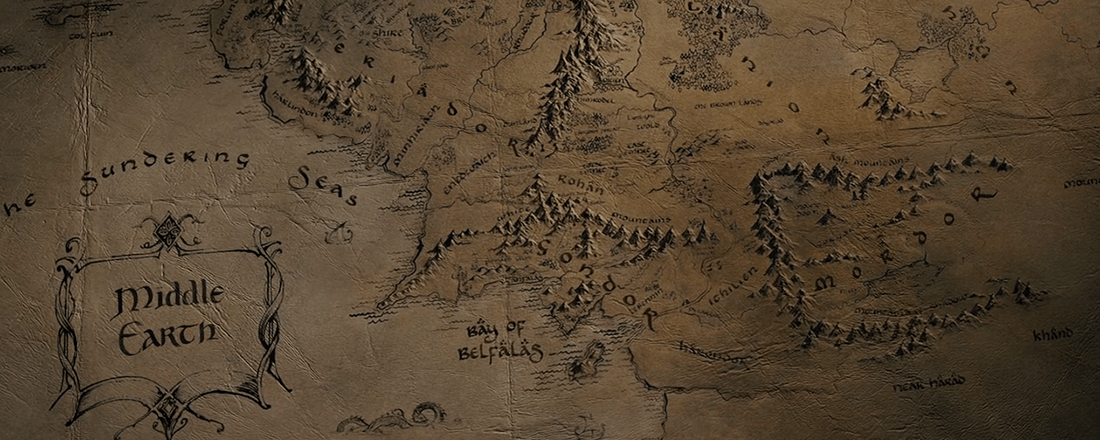

Gandalf the Grey and Aragorn provide the same function in The Lord of the Rings, functioning as guides and mentors and protectors for the wide-eyed and curious Frodo Baggins. Rubeus Hagrid does the same for Harry Potter, much in the same way Spock does for Captain Kirk. (This last comparison is less obvious as everyone in Star Trek seems at home in this world. The difference is Kirk often dives headlong into situations and causes trouble, getting out of it with the help of his crew that explains the statuses quo of whatever world they’re on.) It helps, of course, that all of these characters are charming, warm, and welcoming in their own right. They speak our language as we try to learn the languages of these new worlds.

Map of Middle-Earth from The Lord of the Rings | Source: © LOTR Wikia

Both Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings were released initially in English. The language we hear or read in America and the U.K. is English, even though it’s called Galactic Basic (Star Wars) or the Common Tongue (a phrase used in both The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones) or what have you. The fictional languages remain the same, of course, but when these movies and books are translated and/or dubbed for other countries, what happens to Galactic Basic? Is Basic another language altogether and we just submit our native tongue for it, or, because it was originally written in English, Basic is English, and Basic is then translated into German or Spanish or what have you? It’s a question of narrative distance and, I believe, world building. What is the language the audience speaks and understands? Is it their own, or is it also being translated for them? Who do we identify with? Who is our window? Who helps us understand? Where do we deviate? What characters or worlds do we look at and say, “Now that’s somewhere I want to live?”

After a point it may be irrelevant whether [a fictional language is] English or whatever Earth language it’s translated to, but ultimately, it functions as our way into the world.

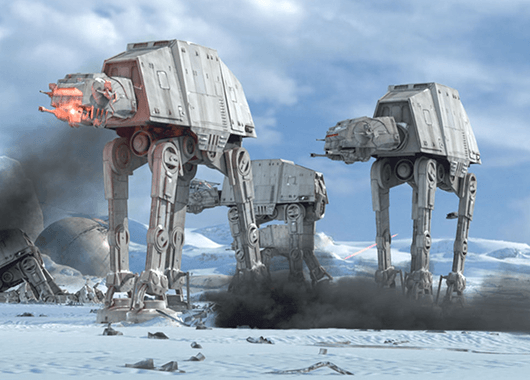

The infamous AT-AT | Source: © Star Wars

In a recent interview, co-creator and executive producer of both Star Wars: The Clone Wars and Star Wars Rebels, Dave Filoni, expressed an affection for different pronunciations. For example, the imposing, mechanized transports that first appeared in Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back, the AT-AT, has been the subject of debate over its pronunciation: is it “ay-tee, ay-tee,” “at-at,” or just — as it has been called — a “walker.” Filoni encourages all uses. Twi’leks from the planet Ryloth pronounce their race “twylek” in the northern hemisphere of their planet, and “tweelek” in the southern hemisphere.

Filoni used these examples to illustrate that a universe is much more believable when things are pronounced differently. He considers it preposterous that everyone across the galaxy would pronounce every word exactly the same way. Why? Because we don’t pronounce things the same in our world. Filoni related that he’s encountered fans who pronounce names of human characters differently because of their own regional inflection, and he celebrates that. At the very least, I think it’s safe to say that Filoni would believe Galactic Basic to be its own language, being “translated” for whomever the film’s audience is.

The point being Galactic Basic, the Common Tongue, whatever, is the reader’s language. After a point it may be irrelevant whether it’s English or whatever Earth language it’s translated to, but ultimately, it functions as our way into the world. Han Solo, Gandalf, Hagrid — they function as translators, not just of language, but of culture. Language and culture, of course, however, are wholly intertwined.

Everyone speaks a language, so characters that do that too — fictional or not — establish a subtle, but powerful connection with your audience.

On Game of Thrones, the character Podrick Payne becomes a squire to a knight, and as part of his education, Pod is instructed that someone of a knight’s class (a higher class) would address a woman as “my lady” and not “m’lady.” In Inglourious Basterds, characters meet a terrible end when they signal the number three with the wrong set of fingers. (No, German isn’t a fictional language, but the distinction in cultural expression reflects the world in which the story takes place.) In The Lord of the Rings there is a language that is the very manifestation of evil, and to speak it is to court misery. There are countless variations on the ideas of language being used to conjure magic (my favorites come from the world of comic books, where Zatanna the witch speaks words backwards; or where Nico Minoru can use a word to conjure a spell, but only once, and to use it again she must use that same word in another language).

The reality I’m trying to drive home is that language is a very real thing. Everyone uses it. It lives and breathes and changes over time, from culture to culture, from region to region. It’s our first line of connection. Therefore it’s shorthand, in fiction, for reality. You can spend time establishing hierarchies and planning cities and writing histories (and, really, you should, because it’s fun; G.R.R. Martin uses his A Song of Ice and Fire series to do more of what J.R.R. Tolkien does with The Lord of the Rings), but the quickest way to immerse an audience is to let characters speak a new language. Everyone speaks a language, so characters that do that too — fictional or not — establish a subtle, but powerful connection with your audience. Combined with a translator, language can be the very thing that grabs your audience by the ear, pulls them into the story, and makes them consume your world wholesale.