KYLE NOLLA

The screen reads, “Loading.”

You’re entering a new world.

In a few moments, you’ll have magic crackling at your fingertips, or perhaps the weight of a futuristic gun in your hands. Maybe you’ll leap across space — into a spice-mining colony galaxies away — or across time — into a medieval village where you could be arrested for accidentally killing a chicken.

But first, you have to choose your character.

![]()

Various video game characters | Source: Remeshed

What is your skin color? Do you have tattoos, scars? Big nose or small? How about weight and build?

And maybe something you took for granted: are you a boy or a girl?

In a game, we actively control the movement, decisions, and the powers of our avatars, and that puts us in tune with their goals and personality traits in an incredibly powerful way.

Although people typically make characters that are cooler versions of themselves, others choose — time and again — to make characters very unlike themselves. Women who always play boy characters; men who only play girl characters. These aren’t a small number of players, either: one survey in World of Warcraft, one of the most popular MMORPGs (Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games; a mouthful, but self-explanatory) of all time, found that 23% of men and 7% of women play the opposite gender. And luckily, I know quite a few of them.

World of Warcraft | Source: © Blizzard Entertainment

Video game worlds are the perfect spaces to explore and perform gender — to be immersed in a story unlike your own or to communicate with others in a new voice. But playing as another gender is complicated in new ways, too. In embodying a new character, we change our behaviors in ways large and small. In performing that character, we draw on and perpetuate stereotypes. These “avatar effects” — coined the Proteus Effect by researchers Nick Yee and Jeremy Bailenson — show that just as much as we influence games, games also influence us. And that ‘dual influencing’ is an important aspect of the gender-switching experience.

Your avatar is the face you present to the world, and the world responds to it in turn.

Research hasn’t reached the point yet where it can tell us exactly why people gender-switch; personal experience is much more useful to us here. However, research can tell us what happens to people when they play as avatars, which is an equally interesting thing to consider.

So let’s play.

The Players who Appreciate Sexy

Men gender-switch their avatars three times as often as women — and, if you’ve ever played a third-person video game, you may have some guesses as to why. Yes, sometimes it really is about butts; when a player is staring at a character’s back for hours every week, they might want to have something pretty to look at. And although it may be less common, it can certainly go the other way, as well.

“I like looking at a hot dude when I play games instead of a lady. I mean, there’s so many sexy ladies all the time. I wanna look at a sexy dude. When I was playing Fallout 4, I put my guy in just a harness for almost 15 levels.”

– Rachel, 25

(Fallout 4 is the most recent chapter in video game company Bethesda’s Fallout series, which is set in a post-nuclear-war America. Players fight mutated beasts, build and support colonies, collect treasures, craft items, and more — all as the character they’ve created).

Character creation in Fallout 4 | Source: Fallout Wikia

Even these players, who don’t necessarily identify with their avatars strongly, can still be affected by their avatars in turn. In the aforementioned study on World of Warcraft, the authors collected and analyzed chat logs and movement patterns, and compared male and female players who did and did not gender-switch. Although the men who played the women identified as men in the usual sense of gender roles, the behaviors they embodied with their female avatar reflected the stereotypes they knew of women. They used more emoticons when they’re chatting and picked hairstyles & outfits that were traditionally feminine and attractive. Their embodiment did not perfectly reflect the female players they might be mistaken for, however; men moved like other men, with lots of jumping and rapid movements, regardless of the gender of their avatar. Another study found that men who play as female avatars in games engage in more direct help-seeking behaviors than they would as male avatars, and receive help from those requests more often too.

Even players who make gender-switched avatars for reasons outside of immersion and self-exploration are still affected in terms of their behaviors by their avatars. The powerful medium of video games can truly alter our reality, whether we intend it to or not.

When players are motivated to play games for action or competition, the character they play is more like a tool than a person. But when someone walks into a game wanting a story, the person who lives that story becomes much more important.

The Players who Explore Themselves

The many facial variations of the Argonian race | Source: The Elder Scrolls Wikia

Your avatar is the face you present to the world, and the world responds to it in turn. Embodying an avatar that’s unlike you can be an experiment in a new self. You can play as a girl and watch as male players give you extra attention, or play as a boy and watch criticism of your gameplay drop by more than half (that one’s a personal experience). With all that considered, consistent gender-switching in social games could be an outlet for people who identify as transgender, genderqueer, or gender-fluid. The game worlds offer another way to present themselves in ways that they may not have the time, safety, or resources to in the real world.

Julia, 25, was assigned female at birth and identifies as agender. Her go-to avatar is the feminine male, or, in worlds which allow it, animal races such as the reptilian Argonians of the Elder Scrolls series. Ultimately, her choice of avatar isn’t motivated by pretty faces or butts; instead, she feels more comfortable playing a male avatar — “for fantasy and release” — and presents as male in voice chats.

“I’m not sure if it’s because I want to feel accepted into the online communities dominated by men, or if I just want to present myself that way. But I feel more comfortable with a male avatar in front of me, and it’s not just to look at their faces or butts!”

– Julia, 25

Ultimately, Julia plays for the story, the challenges, and the communities around games, and although she brings with her a preferred avatar, she still dresses and plays them according to the world. Self-exploration is an element of what motivates her in avatar creation, but it’s not the only element.

Similarly, Noelle, 22, is a friend who identifies as “an enormous white trans woman” and did create female characters like who she wanted to be for a short period of her gaming life. However, that’s not her primary reason for playing characters radically different from herself now — the story is far more important, which we shall find out.

The Players who Weave Stories

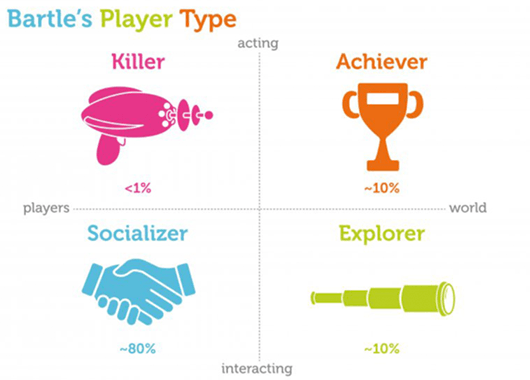

Richard Bartle’s taxonomy of player motivations | Source: RepIgnite

People who design and develop games have created taxonomies for their players as categorizations of player motivation. Are we targeting ‘Killers’? Does our audience want ‘Mastery’? Amid these different types of taxonomies, one type of player always seems to be present: the one who’s in it for the story.

Game developers have risen to meet this demand by creating sprawling worlds with intricate histories, storylines that change based on player choices, and, of course, endlessly customizable character avatars. It makes sense: when players are motivated to play games for action or competition, the character they play is more like a tool than a person. But when someone walks into a game wanting a story, the person who lives that story becomes much more important. A different character can mean a different experience entirely.

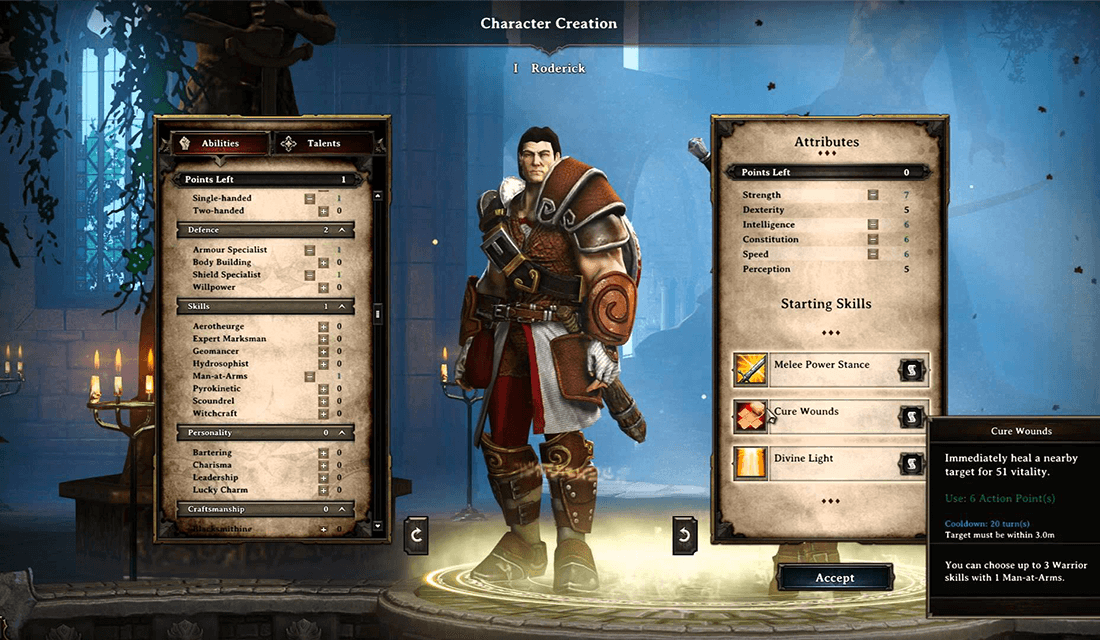

Character creation in Divinity: Original Sin | Source: © GameSpot

So, it’s no surprise that some gamers who are driven by immersion, escapism, and story also choose to gender-switch.

Tom, 25, is a friend who’s completely at ease with his gender, loves story in games, and regularly plays as women avatars.

“I find myself utterly compelled by guiding, and ultimately being responsible for, the exploits of someone that amazes me. And a woman responsible for the complete upheaval of the world in which she lives, and who gains the awe and reverence of everyone witnessing her actions, is someone I would find truly incredible.”

– Tom, 25

Thus, being a woman isn’t so much about ‘being a woman’ as it is about elevating his experience of the game and the story.

Seun, 23, is African-American, male, and plays games for escape, story, and the world. He also plays women exclusively. Although he considers aesthetics in character creation, he’s not simply creating a pretty face.

“In the process of creation, I am entirely concerned with aesthetics, focusing on whatever I think would make my character look best to me. At the same time, an avatar’s story — the one I give for them, mind you, not the game’s own — are a typical part of the creation process for me, and will influence decisions for me when aesthetics cannot. For instance, when deciding if a character would have a scar on their face or an eyepatch, if I like how both of them look, then I will often delegate to story as the deal breaker.”

– Seun, 23

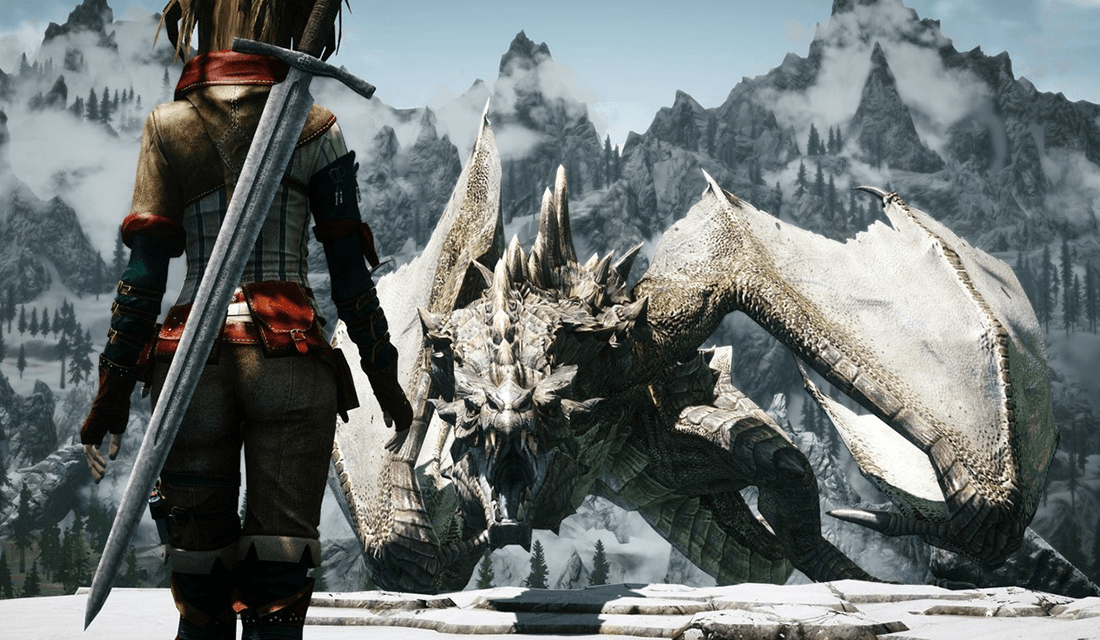

Sometimes, creating an avatar is a way to access a new version of story, as discussed above; however, creating a highly specific and different character can also be a celebration of story itself. Noelle describes her Skyrim experience by saying, “I decided to match the look to the character I wanted to play. The Skyrim character in particular […] was designed to be a terrifying mage of great age, power, and anger. And that was how I played her, too.”

Skyrim | Source: © Bethesda/Forbes

(Skyrim is another Bethesda game from the Elder Scrolls series. It takes place in a typical fantasy setting, with dragons, magic, non-human races such as elves, and little modern technology. Players fight dragons, go on quests for lords and spelunking in caves to find treasures, craft alchemical potions from collected herbs, and so on.)

Tom puts it eloquently:

“I think that a lot of people have a lot of different reasons for playing [open-world RPGs], but for me, it’s the story. And I don’t mean the story that Bethesda writers insert into the games — in fact, anyone can tell you that Bethesda’s writing isn’t exactly stellar. What draws me in is the story that I create for myself through character progression.”

– Tom, 25

How the Game Makes the Player

There are a few things we can draw from all this. First and foremost, controlling an avatar is a measurably different experience from watching a movie or reading a book. In a game, we actively control the movement, decisions, and the powers of our avatars, and that puts us in tune with their goals and personality traits in an incredibly powerful way. Perhaps that’s why so many people find it so rewarding to be immersed in a game with a highly customized, unique avatar — by embodying these characters, we delve into a fantasy escape that’s deeper than what we can experience by being observers alone. Gender-switching takes that immersion and fantasy a step further.

Video game worlds are the perfect spaces to explore and perform gender — to be immersed in a story unlike your own or to communicate with others in a new voice.

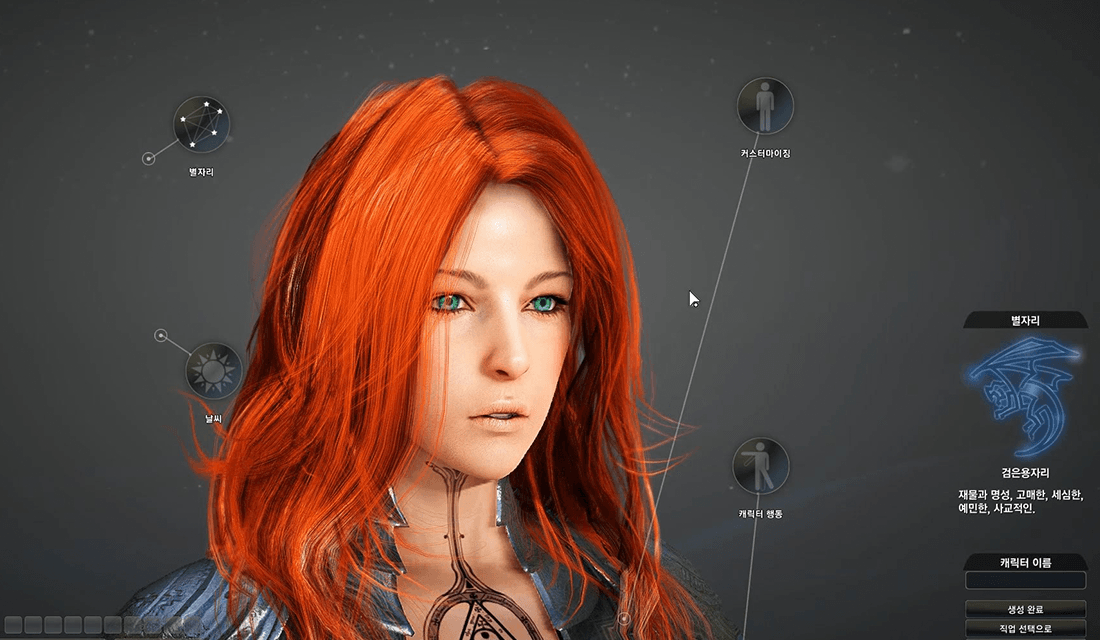

Character creation in Black Desert Online | Source: Gaming Society

But the possibly sinister flip-side to this deep character connection is that, in social contexts, embodying our characters requires us to draw upon the stereotypes that we assume others would make of our character, thereby enforcing those stereotypes whether they’re right or wrong. Although gender-switching with a character may be performative (and, in that performance, often therapeutic), it should not have to mean conforming to and perpetuating a rigid understanding of gender.

For as long as people judge each other based on gender, avatars will be judged and commanded based on those judgments. It’s just one more space where everyday stereotypes are absorbed and amplified back by people who do not live them. But, if there were any place where we could change those patterns, it would be the fantastical and unreal world of gaming.

So, here are some suggestions: Support developers who create fully-fleshed-out characters who are underrepresented in games. Buy and play the games that make you live that character’s life, not just mime it. Or, better yet, find out what those lives are like in the real world. Then, playing them in a game, you can remember that you are still you, not just the “girl version” or “boy version.”

So: Go play. Try on somebody else’s shoes. I’ll be at my Xbox.