TANISHA HUMPHREY

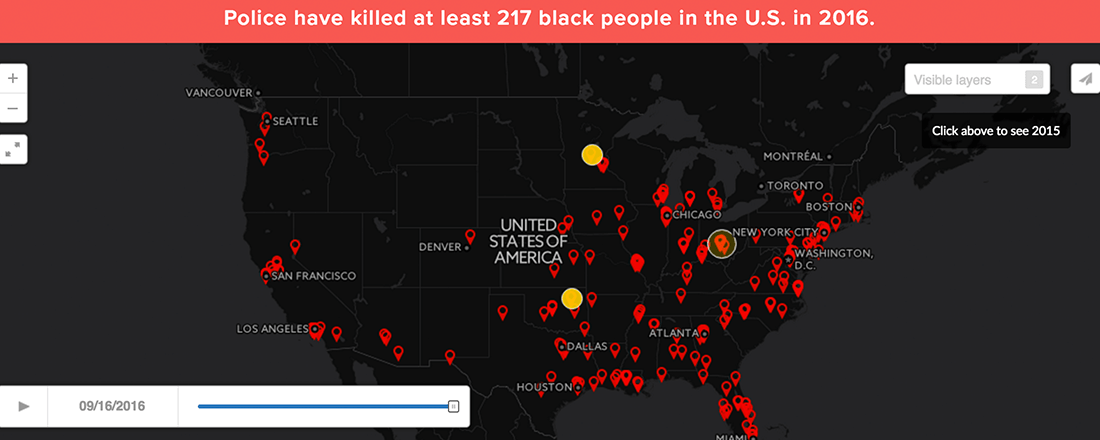

This summer, a deeply painful and very heated conversation about police brutality kept race at the center of American national discourse. Collectively, we grappled with Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and Dallas. As we closed out the summer and fall emerged, we added Terence Crutcher, Keith Lamont Scott, and Alfred Olango to the list. As sure as the list grows longer, the conversation continues.

Source: © OpenStreetMap contributors/CARTO/Mapping Police Brutality

Poster for the critically acclaimed 1959 film Imitation of Life, which explores issues of racial passing, class systems, and gender | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Police brutality is an incredibly polarizing issue, with race forming the line right down the middle. Almost as heated as the conversation about police brutality itself is the conversation about how it should be protested — cities have been rioted, highways and major throughways have been blocked, and athletes have protested our national anthem. Millions of Americans have Googled “What is Colin Kaepernick’s race” and have found dozens of articles to answer this question. To assume anything about what a person believes in based on the color of their skin is problematic — but it becomes even more of an issue for those who pass as White (as well as those who are bi-racial or racially ambiguous). On this issue, as with many others, those who pass as White have their identity and beliefs assumed regardless of whatever truths they personally hold.

In the conversation about race in this country, those who pass as White sit firmly in the middle.

Identity — mutually agreed upon categories for groups of people — is a complex thing. For the most part, we think of race as simply the color of one’s skin. But the identity encompasses more than that. It is partially about physical characteristics — skin color; the color and shape of eyes; the texture of hair; the height and width of a nose and lips; the breadth of hips; the shape of a body. But race also encompasses more cultural factors — nationality; ethnicity; country of origin; immigrant story; family history; language; grammar; music; religion. Because of these cultural and familial components, the lines are not as clearly drawn as we pretend them to be. And yet, if race were just physical characteristics — just skin color — without these significant cultural and familial components, the identity would be so arbitrary; it would be almost meaningless. A person who passes as White may have many of the physical characteristics associated with whiteness — most specifically, a pale complexion — but that means nothing in terms of their cultural or familial identity; this sense of community and the shared story and values that make a racial identity meaningful.

And racial identity is meaningful. I am undeniably Black. I have dark skin, oily hair, a wide, flat nose, thick lips, broad hips, and a big ol’ butt. While I have learned to love these physical characters, my racial identity is rooted in much more than that. When I think about what it means to be Black, I think about clapping and swaying to church songs on Sunday mornings, R&B playing while I get my hair braided, and sticky summers spent riding my bike through my neighborhood. I think about the protectiveness of my older cousins, my mother’s smile, and my grandfather’s generosity. When I think about what it means to be Black in this country, about the hard work my family has put in to get not very far, I feel a sadness as clear and resonant as a bell that I always carry with me. I am the direct descendant of American slaves. This fact means far more to me than the simple skin I’m in. These memories and feelings are deeply personal and have defined who I am. Cultural aspects are central to my racial identity and my racial identity is at the core of how I define myself and how I experience the world.

Quiz from Ebony Magazine, April 1952 | Source: American Studies at the University of Virginia

Race is also meaningful beyond personal identity. Particularly in American society, race is one of the single greatest determinants for whether or not a person will have power, privilege, and access to resource. In almost every factor that we can measure — from the justice system, health care, education, and wealth — disparities persist. Those who have power and privilege and those who do not; those who have access to resources and those who do not; the haves and the have nots; these distinctions are drawn along distinctly racial lines. Historically, this is what has made passing as White so divisive. Passing allows for greater access to resources, power, and privilege. Those who pass are able to walk in the world of the “haves.”

If, as a society, we could find a way to distinguish between and value these two very different groups of characteristics — one physical, the other cultural and familial — that would be ideal. But that is not reality that we are living in, nor has it been the history of this country.

In the conversation about race in this country, those who pass as White sit firmly in the middle. They live daily within the contradictions of structuring our society around something so arbitrary as to be almost meaningless. And yet we know that race is not just skin deep. A person who passes as White may choose to embrace the physical characteristics that allow them to pass in order to gain access to the resources that have a tremendous impact on their quality of life — and, in some contexts, can literally be life-saving. But doing so would also mean rejecting the cultural and familial components that make race most meaningful. What does it mean to have privilege if you can only gain it by ignoring your language or religion? What must it feel like to have access to resources that the rest of your family does not?

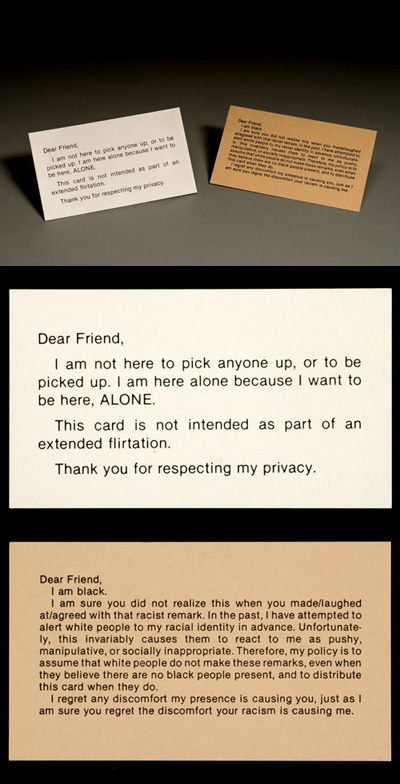

Calling Card (1986) by light-skinned African-American conceptual artist Adrian Piper is a conceptual artwork that consists of a series of cards that Piper hands out to White people who have made racist or sexist remarks to her | Source: © Indiana University Art Museum

This is the tension that people who pass as White must live with. Despite their skin color and other physical characteristics, a person who passes will never be fully White without rejecting their culture and family. And yet that person may never fully feel the sense of community that a racial identity can bring because of their physical characteristics. A person who passes may feel like an outsider in two worlds, never fully belonging to either.

In response to this seemingly ridiculous lose-lose situation, a person who passes as White may simply decide that race doesn’t matter. That person may become so frustrated with people asking “what are you,” and hearing other’s input on a topic that is so deeply personal and yet somehow only skin-deep, that they may decide they can be whatever race people want them to be. Or no race at all. Because racial identity makes little to no sense for that individual, they may decide that the identity itself is completely meaningless and that there should be no race at all.

And to a certain extent, I agree. I also think that race as a concept doesn’t make much sense. Why assume that you know something as meaningful as a person’s origin and family history based on something as meaningless as their eye color and hair texture? If, as a society, we could find a way to distinguish between and value these two very different groups of characteristics — one physical, the other cultural and familial — that would be ideal. But that is not reality that we are living in, nor has it been the history of this country.

Raven-Symonè, who famously told Oprah in an interview that she does not want to be known as an “African-American,” but as an “American” | Source: Alex Calderon/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Race may be something we made up and over time we have struggled to fit people into these boxes that don’t quite make sense. But the concept matters. We have spent so long structuring our society this way that to suddenly pretend that it no longer matters would be disingenuous. Race plays too important a role in the way our society is structured. We saw this with the colorblind discourse of the late 1980s and into the early 1990s. You don’t have to see race to be racist. And, indeed, pretending not to see race makes you more susceptible to your biases and discriminatory or harmful actions. Until we fix racial disparities and have some equality between the races, we cannot do away with the concept, because the inequalities would persist but we would have no way of talking about them.

The concept of race is a somewhat silly, contradictory, slightly illogical concept. But there is no inherent evil in it. Race is not the problem. Racism is.

Source: Library of Congress/Flickr

When those who pass as White actively assert their racial identity, they can play a huge role in shaping the American discourse around race.

Tracee Ellis-Ross, an actress and comedian who’s the daughter of Jewish-American businessman Robert Ellis Silberstein and African-American singer Diana Ross | Source: Mingle Media TV/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Rather than rejecting the concept of race outright, a person who passes as White may choose to embrace their racial identity — their physical characteristics, the cultural and familial components, and the apparent contradictions therein. To accept my own racial identity beyond the color of my skin, I had to do a tremendous amount of self-reflection about what race means to me. A person who passes as White must do a similar exercise to understand their racial identity beyond their physical characteristics. A person who passes as White may choose to embrace the familial and cultural components of their identity and find the sense of community that race can bring.

But this still may not feel like enough. Identity is about mutually agreed upon categories for groups of people. It is not enough for a person to simply hold an identity and believe it to be true — others must also agree. Even when a person who passes as White understands their racial identity beyond skin color and feels a sense of pride in their culture, that sense of identity may often be challenged. They may still face the question of “what are you” and strangers may decide what their race is and where they “ought to” fall on issues such as police brutality.

A person who passes may feel like an outsider in two worlds, never fully belonging to either.

Having your racial identity challenged in this way can be deeply hurtful. Once a person has worked to understand and embrace their racial identity and what it means to them, having that understanding be challenged or ignored can feel like someone is challenging your true self. Those who pass as White may choose to assert the cultural and familial aspects of their racial identity such as their language, religion, immigrant story, etc. — and this is not deception. It is not pretending to be something you are not. It is a way of claiming your identity more fully. The performative aspects of identity allows those who pass as White to not only be their true, fuller selves, but also to resist a world which will constantly tell them what their race “should” be.

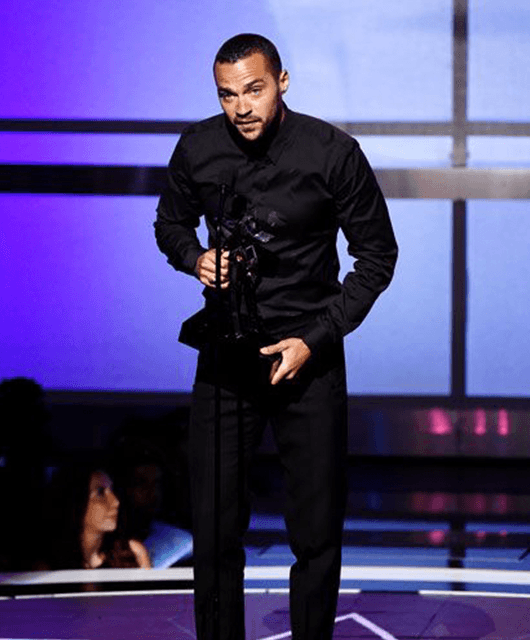

Jesse Williams at the 2016 BET Awards | Source: © Kevin Winter/Refinery29

When those who pass as White actively assert their racial identity, they can play a huge role in shaping the American discourse around race. This summer, we saw Jesse Williams give a powerful speech on race at the Black Entertainment Television awards. He took all of the privileges associated with having fair skin and light eyes and used it to drive the cause of racial justice forward. We already talked about Colin Kaepernick using his status and position to continue calling attention to these very same issues.

Identity is simultaneously a deeply personal and very public thing. Passing as another identity can feel like having your true self ignored. But those who choose to resist this passing and instead actively assert their identity can be tremendously powerful. When those who pass choose to actively assert their racial identity, they are not only able to be a fuller version of themselves — they may also change the conversation for the better.