KELLEY KIDD

In this issue we talk to Deb Sivigny, a theatre designer and artist as well as creator of Hello, My Name Is…, an immersive “seven-room living installation” set inside a standalone house in the middle of a residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C. Produced by The Welders, the deeply personal play touches on themes of adoption, belonging, and the meaning of home. Deb’s set design and the direction of the play by Randy Baker have both been nominated for the 2018 Helen Hayes Awards.

Hi Deb, thanks for making the time to do this interview!

First off, can you tell us about Hello, My Name Is… for people who don’t know anything about it?

Deb Sivigny

Hello, My Name Is… is hard to describe, but I would start by saying: it’s a site-reactive, design-led, semi-autobiographical, immersive theatre piece staged inside a house for an audience of fifteen people.

In order to talk about it, I have to define what each of those pieces means.

Site-reactive:

Instead of site-specific — where a play or event is developed with knowledge of an existing space in mind, and that space is incorporated and essential to the plot (ie. a piece about a car mechanic set inside a garage, or a restaurant play set inside a restaurant) — site-reactive describes a slightly different working model. Before finding the venue, I wrote many small vignettes which eventually combined to become the script for Hello, My Name Is…

Once the venue was guaranteed (Rhizome is a two-story house), I had to adapt the plot to fit the space and take advantage of what the space gave to the script. I cut scenes that weren’t going to make any sense in a domestic space, and explored many more with the ensemble that took on new meaning inside the house.

Design-led:

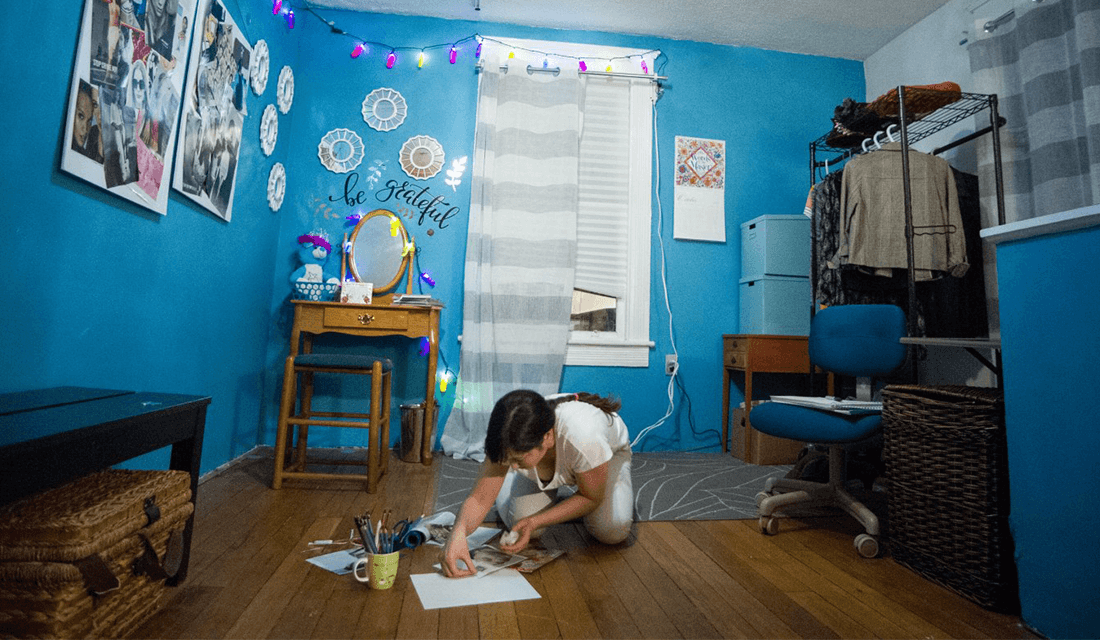

I identify as a designer, not a playwright. This title could be encompassed by the name “Playmaker,” but the hybrid nature of the role designer/playwright is meaningful to me. I set out to create a process that was led by the visual before the verbal. Obviously it took words to communicate these ideas with my team, but I began with what I knew how to do best: visual research, ground plans, and character study.

One of the adoptees, Bryan (played by Jon Jon Johnson) in his room, writing unsent letters to his birth mom | Source: © C. Stanley Photography/Randy Baker

The eventual script became a mix of room/mood descriptions, movement ideas, dialogue, and furniture configurations. The structure of the piece comes from the architectural logic of the house: living room and dining room on the lower floor, bedrooms on the upper floor. The production team purposely played with the expectations the audience had before subverting them in the second half of the play.

Semi-autobiographical:

The main story follows the lives of three Korean adoptees [June, Dana, and Bryan] from developmental years to adulthood. As a Korean adoptee myself, I spent two years studying and interviewing my adopted peers, finding similarities and differences, and creating short narrative pieces based on anecdotes and memories. There are small details of my own story inside the piece, both in the text and the visual world, but they are fragmented between the three adopted characters.

Immersive:

There are so many ways to describe immersive theatre, but I was most interested in taking the audience on a journey where they would be a part of the world in various ways. The piece begins as Aunt Rosey welcomes the audience into the house, feeds them, and thanks them for coming to her party. The living room of the house is realistically decorated like a Midwestern living room from the 1990s, with the stylized choice that every object is beige. As the group tries the hot dish and chips and writes on a welcome sign, they learn they are at a “Gotcha day” party for June, the adopted girl. When June arrives, she is taken to her room upstairs, the audience follows, and they witness her discovery of her new bedroom. She is scared and curious, and the audience likely feels the same way. By using simultaneity of emotions, everybody moves toward the same headspace.

The audience and June (played by Linda Bard) in her new bedroom in America | Source: © C. Stanley Photography/Randy Baker

Ultimately the piece is about three adoptees trying to find and define a meaning of home for themselves after a lifetime of questioning or ignoring their circumstances.

Can you tell me about your journey leading up to writing Hello, My Name Is? What were the experiences that immediately prompted you to tackle writing this story?

Deb Sivigny

Creating Hello, My Name Is… has been affirming and eye-opening for me, as a playmaker, an Asian-American, and as an adoptee.

I had an incredible opportunity as a member of The Welders, which is a playwrights’ collective in Washington D.C. We each take a turn leading the group while also writing/creating a play of our choice. There are seven of us and we’re halfway through our tenure. We’ll pass on the entire organization in 2020 to a new group of playwrights.

A few years ago, when we applied to be the second generation of Welders, we needed to pitch an idea for a play as part of the application. I had been thinking about traveling to Korea as a bucket-list kind of thing, so I wrote a visual poem about family trees and airplanes. When I traveled to Seoul by myself in July of 2015, I made an appointment to look at my adoption file, met with adoptees who lived there, saw a ton of art, and cried every day. It was an awesome and terrifying experience. My travel buddy was my sketchbook/journal. I took it everywhere.

Turning the living room into a Korean Air flight to Seoul for the audience and Dana (played by Janine Baumgardner) | Source: © C. Stanley Photography/Randy Baker

When I was on the plane home, I created a list of 50 things that interested me enough to write about or research. I pursued the ones that were most visually stimulating to me and the ones that found common ground with other adoptee stories. I knew that I didn’t want to write an autobiography because the Korean diaspora of adoptees, if you will, is vast. What has been most important to me is that this story is told from an adoptee point of view. So much of the narrative of adoption has centered on parents, or been marginalized into tropes about adopted people. And frankly, the stories are rarely told onstage, especially in their complexity, so it’s about time.

In the description of the show, you mention that you find the experience of all adoptees to be one of being both insider and outsider.

Are you open to sharing a bit about how that experience has shown up in your life?

Deb Sivigny

Confronting this part of my life has been a long journey of denial and erasure. Growing up in rural Connecticut wasn’t the best environment to be Korean, but it was an amazing place to be a kid. I had a racial mirror in my Taiwanese (adoptive) mother, but as many immigrants desire assimilation, she was interested in my ability to fit in and be the best student. I have both my parents to thank for getting me to the place I’m in now, but I feel a distinct loss in my Korean-ness that I’m trying to regain as an adult. I still grapple with the fact that I often “feel white” despite being a person of color. Transracial identity is a real issue in adoptees. I’ve never felt quite Asian enough in Asian spaces, and never white enough in white spaces.

One part of my life where this manifests frequently is that of language. I speak about five words of Korean, all learned in the past three years. When I traveled to Seoul, people expected me to speak the language. It was extremely hard to navigate spaces because I didn’t get any help. I’ve compared notes with white friends who have traveled to Korea-they don’t have any trouble because people swoop in to help them and complement their attempts to speak Korean. I frequently felt stupid. This feeling was echoed by the adoptees who moved back to Seoul and felt the need to learn the language with native fluency. It remains a goal of mine to learn Korean, but I have no goals of fluency. In contrast, I have never had the feeling of fitting in quite so well as I did in Seoul. Walking down the street and being recognized as Korean, and seeing my face mirrored in the people was an incredible feeling. I had traveled to other Asian countries (Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia) but the feeling was even more palpable in Seoul. Another place where [I] sometimes feel like in an insider is when I’m working on theatre needing dramaturgy regarding Asia/Asian-America. I like feeling culturally literate. It’s generally a good feeling, but sometimes results in tokenization if I’m the lone Asian on a team. The line between acceptance and being taken advantage of can be a fine one.

What were some striking examples of the themes that you heard or wrote about in the stories of others, if you feel comfortable sharing?

Deb Sivigny

Four themes came to the forefront:

- Displacement/imposter syndrome

- Never being good enough

- Race denial/dissonance

- Gratefulness/saviorship

June (played by Linda Bard) arriving home in America | Source: © C. Stanley Photography/Randy Baker

Sometimes the themes are deeply embedded in the stories, but often they’re explicit. I think transracial adoptees frequently feel like they’re on the outside. They’re a minority inside a minority, but often being raised by white people. This can create a dissonance between thinking they’re part of the majority, alongside experiencing racism and micro-aggressions because of how they look. It’s confusing and can cause a rift between parent and child, then eventually how they see the world as an adult.

There’s another aspect of growing up as an adoptee that can be encompassed in the word “saved.” One crass but very real view is that adoptive parents saved their children from third world countries that didn’t want them. Often the second part of that sentence includes some reference to “God gave them this gift.” I don’t intend to blame Christianity or religion for the racial brainwashing of adoptees, but there is a definitely a streak of agencies that use this saviorship-style reasoning for why people should adopt children.

June arrives in the office of The Ultimate Mother (played by Wyckham Avery), head of the Christian adoption agency in Seoul responsible for the adoptions of June, Dana, and Bryan | Source: © C. Stanley Photography/Randy Baker

The theme for this issue revolves around utopia and childhood. For me, this theme and the subject of adoption brought to mind the stories of children taken from Vietnam during the Vietnam War, with the default assumption that coming to America would offer them a “better life.”

Is that an assumption you find you encounter when talking about your adoption experience with people? Did that play into your process at all?

Deb Sivigny

This is one of the main [themes] I learned the piece was about. When I originally set out to write the piece, I wanted to tell a multiplicity of stories, mostly based on misunderstandings and stereotypes about adoption. What I learned as I talked with people is that different assumptions are all over the place about adoption. The “better life” narrative is everywhere, and in some cases, this is probably true. There are circumstances in many countries — Vietnam, Haiti, Ethiopia, Korea in the early years — when war or natural disaster created a new group of “orphans.” What many people don’t know or consider is that for countries like Korea or China, the rules and circumstances have changed over the years. Many of the children up for adoption are not orphans at all. Myths get perpetuated and histories get erased.

Luckily, what is changing now is awareness — of the truths of adoption and awareness on the importance of race, racial mirrors, and the politics of citizenship. I was very aware of what utopia needed to look like when creating June and Dana’s personal spaces. June’s bedroom is a fabricated pink palace of 1990s bedroom furniture. Giant teddy bear, shelves of dolls, pink décor… a young girls’ dream. However, it’s not her creation — it’s the ideal that her adoptive parents have made for her. She has no agency in this space. Dana’s teenage loft shows a little more agency, but what’s missing in her space is any consideration of her race. Audiences witness her desire to “be white” through the putting on of makeup, and dressing like her [white] friend, Meredith. When she ends her vignette with a glimmer of a future more aware viewpoint, it’s still naïve and new to her.

Dana (played by Janine Baumgardner) in her room, decorated with quintessential American pop culture | Source: © C. Stanley Photography/Randy Baker

What has your process of re-connecting to the place you came from been like? Has it changed your perspective on life and culture in America, and if so, how?

Deb Sivigny

I am glad to be finally embracing Korean culture in healthy ways. Enjoying the food has been a great way in. I also want to lift up the Korean adoptee groups online —they’ve been a great source of information, support, and understanding. It’s reassuring to know that there’s a community just like me out there in the world. Personally we’re very different, but our shared experience really matters.

America is really a place unto itself. There are many things that are undeniably American in the world; I don’t tend to notice them until I leave the country. Some things are as subtle as the way I stand or walk, or my gaze. I’m aggressive in contrast with my Asian neighbors, which always takes me a moment to realize. Americans point at things. They look you in the eye. They’re loud, but I’m reflected more in American culture than Korean culture.

Tying into our theme in a different way, what’s your dream version (or utopian version) of this production?

Deb Sivigny

I don’t have a utopian version, except to fulfill my wish of doing it again with the same ensemble. I could not ask for a better group of collaborators.

Thanks for your time Deb, and good luck with your projects!

Deb Sivigny:

Has been designing in the Washington D.C. area for almost two decades and is the resident faculty artist in the Theatre and Performance Studies department in Georgetown University. Last fall, she wrote and set designed Hello, My Name Is…, an immersive event about Korean adoptees at The Welders, where she is a Producing Playwright. Her work with The Welders and Forgotten Kingdoms at Rorschach Theatre (company member) was nominated for the Helen Hayes Awards Outstanding Set Design category, as were her costume designs for Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom at 1st Stage. She has also designed for Forum Theatre, Adventure Theatre, The Hub, Woolly Mammoth, Round House Theatre, Olney Theatre, Colorado Shakespeare Festival, and Everyman Theatre, among others. She is a proud member of USA 829. She has a BA from Middlebury College and an MFA from the University of Maryland. DebSivigny.com