SHALINA CHATLANI

Augusto Boal | Source: Cedoc – Funarte/Beautiful Trouble

Anyone can go to the theater, and that is the point. Performance is where inhibition melts away. It’s where the eccentricities within the individual characters and audience members intertwine to create something beautiful: a dialogue on nature. Augusto Boal, a Brazilian director and political activist, brought this idea to the real world through his original “Theater of the Oppressed,” an international movement that encourages participatory theatre as a forum for cooperative interaction and dialogue on forms of oppression. With his modern spin on Shakespeare’s famous saying, “All the world’s a stage,” Boal saw theatre as the point at which democracy truly begins.

The theatre, for Boal, is where democratic dialogue is born and easily accessible.

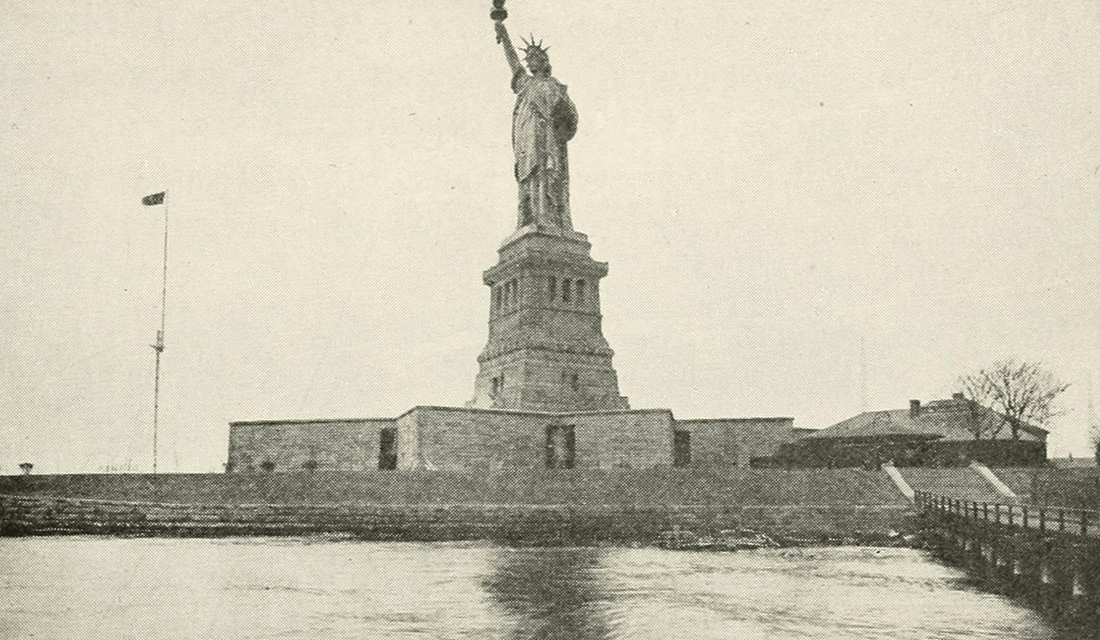

While the director first experimented with participatory theatre in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in the early 1960s, the United States has long prided itself on his performative narrative: the idea that the nation is an arena where the “oppressed” — politically, economically, racially, culturally — can interact and unify. The act of becoming one of Boal’s “spect-actors,” a dual observer and actor, is what has generally been understood as “being American.” It’s a performance of diasporan identities, with roots in different places and cultures, coming together on the static stage — the so-called “melting pot” — that is the United States, or the American nation as a theater. With continued rhetoric on exclusivity proliferating throughout political discourse in the nation, however, one cannot help but question whether the infrastructure of this stage is crumbling at its core.

Source: Internet Archive Book Images/Flickr

In an interview for Democracy Now, Boal explains that “theater is what we have inside,” because “we are acting all of the time,” and at the same time, “we are spectators of our actions.” The actors, he observed, are “all of us,” and the performance is a dialogue on human nature that exists between “men and women, blacks and whites, countries in northern and southern hemispheres.” The oppression exists when the dialogue becomes a monologue in which only “men speak, only whites speak, only the northern countries speak.” The theatre, for Boal, is where democratic dialogue is born and easily accessible.

But, what happens when some of the participants decide to undermine the dignity of the performance?

For many, the United States has been the idyllic manifestation of Boal’s “Theater of the Oppressed.” The ‘American Dream’ has been the ethos of the United States, since historian James Adams popularized it in his 1931 book The Epic of America. Diasporan populations that come to the United States are able to unify within their respective cultural identities as well as static identity of location — yes, we come from different places and maintain those ties, but this is where we choose to stay, cooperate, and find harmony. This is the theater where we, in our capacities as “spect-actors,” can live democratically and engage in a dialogue, both observing the way people interact, and slowly becoming one of the “interactors.”

Source: U.S. National Archives/Flickr

But, what happens when some of the participants decide to undermine the dignity of the performance? It’s beautiful that the United States is often characterized as being the land of dreams, but this idea of America as a theater — the rhetoric of unity among multiple identities — is losing, and for the most part, has already lost its foundations. Dialogues are increasingly becoming monologues. The performance is being dominated by the rich, the white, and the elite. And, those with diaspora roots are finding it increasingly difficult to find a static identity within the nation.

This phenomenon is promulgated by antagonistic characters that manipulate and add to divisive rhetoric within American society. The lack of unity is being promoted by the media channels that inspire fear and the “otherization” of certain ethnic groups, by politicians that try to control women and their bodies, and by police officers that racially profile their suspects.

Police mace demonstrators in North Minneapolis on November 18, 2015 | Source: Tony Webster/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

[The] American public needs to reflect on whether the United States is truly as free and equal as it is reputed to be.

What’s particularly troubling about these degrees of separation is that the actors are conscious of their efforts and actively fail to consider the spectators. One of the most obvious examples of this reality is the 2016 U.S. presidential race, in which each of the candidates has only contributed to overwhelming schismatic language in American rhetoric.

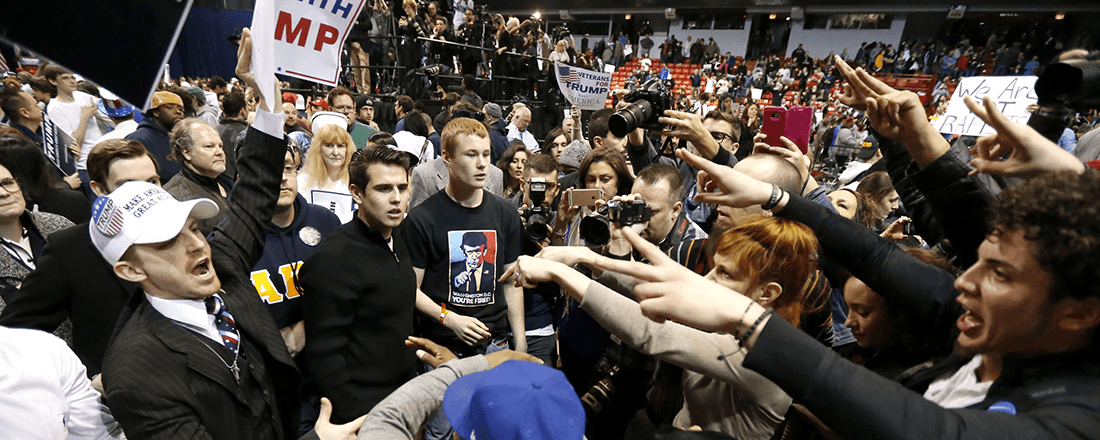

The race has been characterized by conversations on building walls, tagging religious groups out of fear, and blaming segments of the population for the nation’s problems. There hasn’t been a discussion about the need for Americans to foster a unifying attitude and to cooperate on social and political issues. This trend is dangerous, particularly because the country has been built by diaspora populations that sought refuge in the static location of the United States and hoped to transition culturally and socially into American society. It’s increasingly difficult for groups to find their place when even the potential president of the country is incapable of promoting union — physical altercations at election rallies, name calling and patronizing on the stages, scapegoats continuously identified.

Protestors clash with Trump supporters | Source: © Charles Rex Arbogast, AP/USA Today

Politicians are not the only ones at fault here. The American public is also contributing to the overall shift away from the ideal — the melting pot history books pride us with being — by taking steps backward. Look towards college campuses, where young Americans are learning to become leaders, and find racism, classism, and unrest. At Yale, students drew swastikas on campus steps and some even allegedly banned black women from a fraternity party, according to a The Atlantic article. The University of Missouri has been highly scrutinized in the past year for a number of racist incidents, which included actions on the part of the president at the time, Tim Wolfe. The examples can go on for days. But, the main point is that the American public needs to reflect on whether the United States is truly as free and equal as it is reputed to be.

The result is a tearing apart of the core American ethos, and it is petrifying.

These examples demonstrate that American performance and conversation is one-sided — that there’s no synergy between the audience and the actors. The statistics already speak for themselves. It’s true that women earn less than men, segregation still exists among the races, and that millennials think differently from older generations.

At one point in time, though, to be American, at least within our conversations, was to perform against those binary relationships, to come together in a theater, and appreciate our diversity while seeking change and moving forward. The identity was juxtaposed with dreams of women getting the right to vote, all race groups being granted equal opportunity, and employees receiving greater protections at work. Increasing polarization in American political and social discourse, however, is making the development of a dialogue impossible. America as a theater is not longer a tool for combatting oppression, it’s a stage for the oppressors to have their monologues.

[America] has been built by diaspora populations that sought refuge in the static location of the United States and hoped to transition culturally and socially into American society.

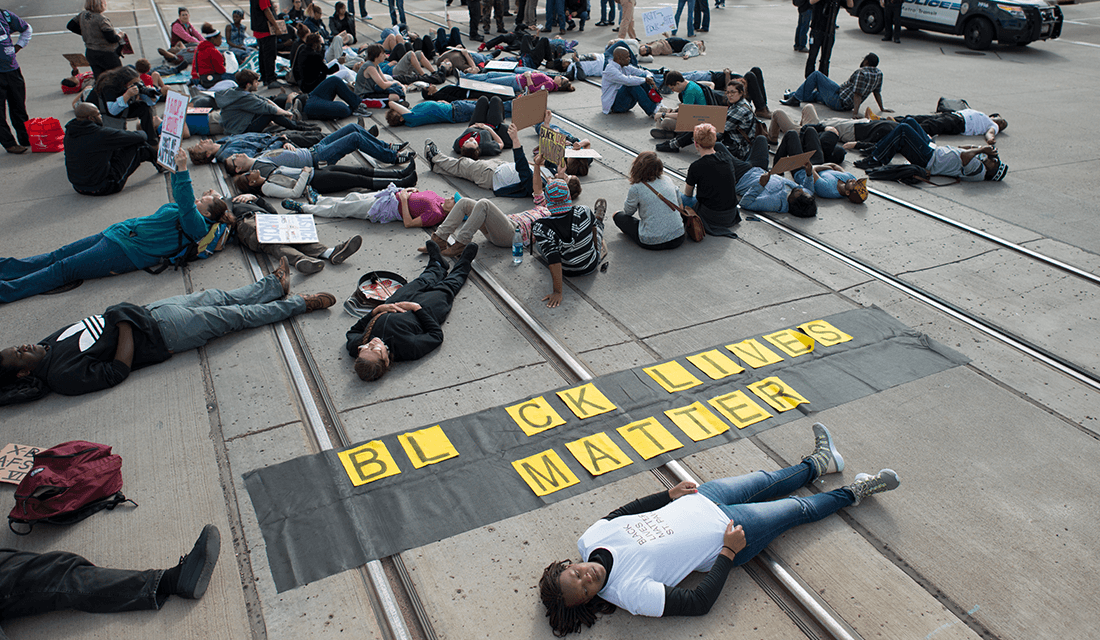

How can characters with non-dominant and diasporan identities — including racial, socioeconomic, and ethnic — find unity within their static location if the popular actors are performing exclusivity? Simply, the unified stage disappears. People have had to turn to their own arenas — Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, feminist movements. There are no longer “spect-ators” for the American theater, only observers and performers. The result is a tearing apart of the core American ethos, and it is petrifying.

Black Lives Matter protest in St. Paul, Minnesota | Source: Fibonacci Blue/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Recognizing the lack of unity, many within minority populations have contended that the American dream is a farce. A The Atlantic article interviewed citizens around the country on whether they still believe in it. A number of interviewees still believe in the concept, seeking to keep the performance alive. Richard Mahfouz from Arkansas recalled his roots in his ethnic diaspora from the Middle East:

“Anyone can succeed and be free here if they are willing to work. My grandparents came from Syria escaping persecution. They came through Ellis Island to Arkansas, and built this store with their own hands.”

– Richard Mahfouz

But another handful acknowledged the lack of willing engagement within the United States.

Chaka, from Albany, for instance said, “I don’t believe in the American dream anymore. Nothing comes by just being here.” Robert McAdams, from Nebraska, mentions the role of the politicians:

“The American dream is long gone. Long, long gone. Politicians have ruined it, broken our values, sold out to folks with money who only care about themselves. Nobody cares about anyone who works with their hands anymore. We got to get this country straight again, before it all keeps sliding down into hell.”

– Robert McAdams

Boal leading a workshop | Source: © Augusto Boal Archive UNIRIO/Critical Stages

Here, we can zoom out and consider Boal’s “Theater of the Oppressed” once more. While the U.S. may not be the ideal representation, at least in terms of language, of his thesis, the people dominating the stage ought to heed his words, at least for the sake of American democracy.

Boal’s method has spread throughout the world, and until his death, he continuously put on workshops to encourage progressive dialogue. In fact, such workshops have been performed not only in the U.S., but even rural villages in West Bengal, according to an article from Al Jazeera. His vision to develop a “political theatre whose fundamental premise” was to let “people talk” has been adopted by Jana Sanskriti, a Bengali theatre company. The organization has encouraged people to “travel long distances […] at the day’s end to act, sing and dance,” and discuss community matters.

What’s striking about the story is the democratic element. As a result of the dialogues that were formed by the theatre company, the village created an active Human Rights Protection Committee in 2001. The author of the Al Jazeera piece sees the example as evidence that “theatre forums are efficient tools to design better politics,” and that they can “activate democracy.”

A solution to the loss of unity in location among diasporan populations in the United States can be the recognition of Boal’s sentiment that all of life is theatre. The performers, namely politicians, should understand that their words and actions are part of a larger show, and that audience not only observes them, but interacts with them.

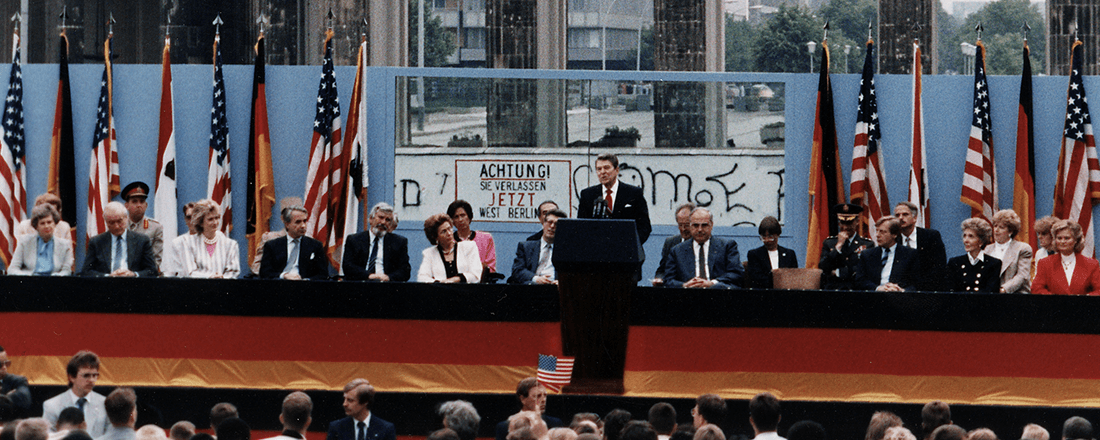

U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the Berlin Wall | Source: U.S. National Archives/Wikimedia Commons

Those candidates on a literal, televised stage should realize that their words are inspiring, often infecting American youth and their interactions with other actors. At the same time, the American public needs to stop taking steps backward and reflect on their sentiments. We must steer away from potentially divisive rhetoric that undermines the heart of the American ethos.

By recognizing Boal’s sentiment that “we are always acting,” and, conversely, that people are also always observing, perhaps democracy will come as a byproduct to a healthy dialogue and engagement. It’s the sentiment of speaking with, instead of at each other.

Diversity and the multitude of ethnic identities ought to be cherished in this nation, and the destruction of the central theme of coexistence would mean the end to one of history’s most profound productions — a show that has taken years of movement and change to slowly improve: the end of slavery, the right for women to vote, the Civil Rights Movement, Labor Rights Movement, LGBTQ movements.

Protesters at the University of Missouri gather | Source: © Michael Cali/San Diego Union-Tribune/TNS/Daily Signal

Years of cooperation have shown that people in the United States seek to become “spect-ators,” but that select characters may be threatening that integrity of that institution. As the presidential race continues, as American society moves forward on a variety of issues, the polarizing rhetoric must not become a defining component of the culture. That would spell the complete destruction of the American theatre, right when the show’s about to get interesting.